Lifting the lid on Australia's child sex abuse

- Published

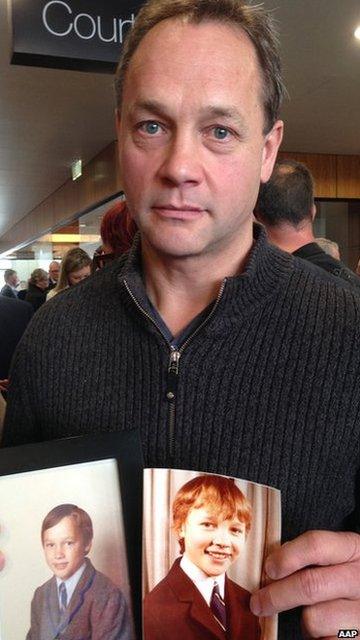

For decades, Peter Blenkiron remained silent about the abuse he had suffered at age 11 at the hands of his Catholic Christian Brother teacher.

Earlier this year, Mr Blenkiron relived the horror of his school days, telling an inquiry into child abuse about how he would be pressed against the wall at the back of the classroom while his teacher physically and sexually abused him, with the other students ordered to look away.

"If there was no sexual abuse after the belting, then you knew you'd had a good day," the 53-year-old told a hearing of Australia's landmark Royal Commission, external into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse.

Giving testimony from his hometown Ballarat, in regional Victoria, and hearing harrowing stories from other survivors of child abuse brought back the pain, Mr Blenkiron told the BBC.

"I was a mess for about two months," he says.

But he was determined to shine a light on the abuse that has claimed the lives of many of his peers, through suicide and substance abuse, and that turned him into "a ticking time bomb".

Peter Blenkiron lives with the horror of the abuse he suffered as a child

The Royal Commission is an historic opportunity to draw a line in the sand under that pain, he says.

"It has to uncover the horrors of the past, it has to help those who were affected to get the best possible ongoing support today, and it has to make sure all our children are safe in future," he says.

That's a measure of the huge challenge facing the Royal Commission, set up in 2013 in response to public outrage over allegations the Catholic Church had for years covered up evidence about paedophile priests.

The then Labor Prime Minister Julia Gillard promised the investigation into how government and private institutions responded to allegations and instances of child sexual abuse would "change the nation".

The signs are hopeful, with the Commission acting on a scale and scope that few expected, and with a sensitivity to those abused that the UK's fledgling Independent Inquiry into Child Sexual Abuse has indicated it may follow, external.

Commissioners have so far held 32 public and 4,000 private hearings across Australia

But the stakes are high. Many victims - or survivors as the Commission describes them - want people at the highest levels to be held accountable, and they want meaningful compensation.

Over the past two and a half years, six commissioners have held 32 public and 4,000 private hearings at sites across the country, from an outback orphanage run by the Sisters of Mercy to one of Australia's most prestigious schools, Geelong Grammar, once attended by Prince Charles.

It has documented abuse by teachers, priests, nuns, foster carers and fellow students, and this year, extended its investigations into sporting bodies and the entertainment industry.

It will make recommendations on how to improve laws, policies and practices to prevent and better respond to child sexual abuse in institutions.

Commission's work so far

Confirmed 12,000 allegations of abuse relating to 3,500 religious and state institutions

Referred 727 matters to police

Receives, on average, 40 requests per week from victims for private hearings

Held community forums in dozens of regional towns and cities, including in remote Aboriginal communities

Last year, the Australian government granted the Commission's request to extend its work for another two years, for a total cost of about A$500m ($351m, £231m).

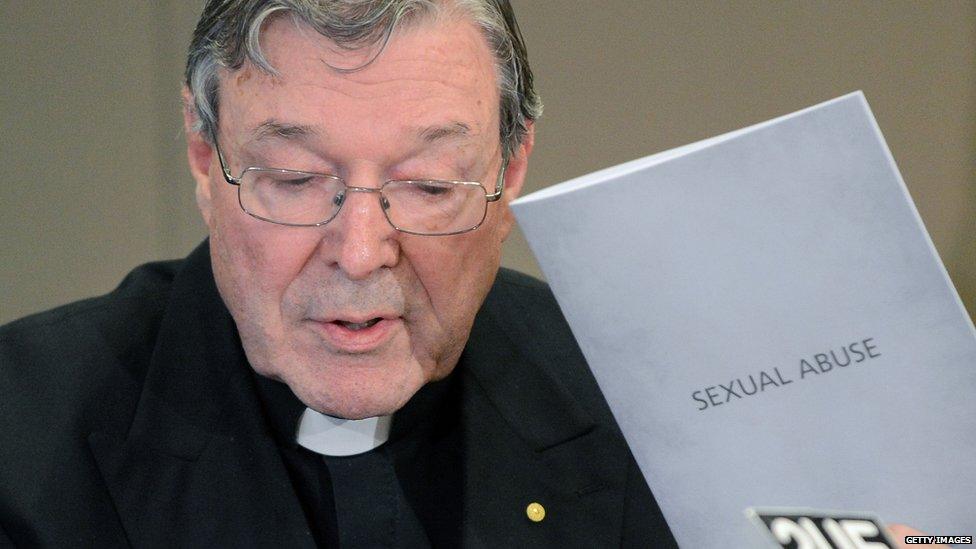

It has called high-profile witnesses to give evidence about what they knew of abuse in their institutions, most notably Australia's most senior Catholic Cardinal George Pell, who is now the finance chief at the Vatican.

The Commission, which will report at the end of 2017, has exceeded expectations by highlighting abuse "from almost every area of society, every walk of life", and by showing that such abuse continues today, says Sydney University Law Professor Patrick Parkinson.

"They've been very wise and shown beyond reasonable doubt the level of the problem in Australian society and the level of cover-up," he says.

Catholic Cardinal George Pell has denied allegations of a cover-up

Its impact is apparent, he says, with organisations "scrambling to review their policies and procedures" about child protection and very senior people "embarrassed" by their failures to prevent or report abuse.

But he says there are big issues to settle, including the Commission's call for Australian governments to set up a single national redress scheme for survivors.

Such a scheme is estimated to cost up to A$4bn but would still only pay compensation of, on average, A$65,000 per survivor. Many say that is not enough.

In any case, the federal government has said it will not be part of a national scheme, a response that shocked many survivors who fear they will have to deal with the very institutions involved in their abuse if they want compensation, says lawyer and doctoral researcher Judy Courtin.

There are growing calls from compensation to be paid to victims and carers

It is too early to judge whether or not the Royal Commission will meet survivors' expectations, Ms Courtin says.

Her research shows survivors want to tell their stories and have them publicly acknowledged, to hear the truth from institutions about what happened, to be compensated for the long-term impact on their lives, and for those in senior positions who concealed abuse to be held accountable.

"They want the bishops and others who have covered up crimes to be criminally accountable," she says. "That's high up on the list."

The Commission's work has prompted more police prosecutions of historic cases of child abuse, says lawyer Warren Strange.

In the past, a lack of witnesses and the fact it can take most victims up to 20 years to report their abuse have been stumbling blocks for police investigations.

But Mr Strange says any long-term systemic change about how institutions deal with claims of abuse will be more important than the number of prosecutions that result from the Commission's work.

He is an executive officer of knowmore, external, a government-funded independent free legal service that is often the first point of contact for victims who want to give evidence to the Royal Commission.

They come, he says, from all backgrounds - from great disadvantage to people with successful careers.

They want the scale of what happened and the failure of institutions to respond appropriately exposed. But the main motivation for many of the people who tell their stories is not about themselves, he says.

"They say 'I don't want what happened to me to happen to any other children in future'."

- Published27 July 2015

- Published27 May 2015

- Published15 June 2015