What is behind a spike in Australian shark attacks?

- Published

Ballina's Shelly Beach on the far north coast of NSW after Japanese surfer Tadashi Nakahara, 41, died following a shark attack in February

The number of shark attacks in New South Wales has been particularly high this year, even though estimated shark numbers are at record lows. What is behind this mystery? The BBC's Phil Mercer in Sydney talked to some of the experts.

It has been a nasty year for shark attacks in Australia. There have been two fatalities recorded so far, 29 attacks and 18 injuries.

In New South Wales (NSW) alone - Australia's most populous state, there have been 13 attacks recorded so far, seven injuries, and one fatality.

And that is despite the number of estimated shark numbers along the coast of NSW being at record lows.

What is also a mystery are the sharks' migratory movements and true population numbers. But understanding this could be the key.

One theory is that changing ocean currents are driving sharks far closer to the shore, says Dr David Powter, external from The University of Newcastle in NSW.

"I tend to think we're getting a confluence of factors," he told the BBC.

A shark tagging program on the north coast of NSW is helping track migratory movements

"You're getting the movement of those currents [which] bring the bait fish. The larger fish then follow the bait fish - and then the predators follow.

"And that is probably why we are having these spikes from time to time," he explained.

'Unusual blip'

Leopard sharks like Brian, who resides at Sydney's Sea Life Aquarium, are harmless to people

At Sea Life Sydney Aquarium, Brian the leopard shark has a home at the vast Great Barrier Reef exhibit.

Unlike his more fearsome cousins, this graceful bottom-dweller doesn't have sharp or serrated teeth. Instead, he has a mouth built for crushing shellfish and molluscs - and he is harmless to people.

Great whites, bull and tiger sharks, on the other hand, are among those blamed for savage ambushes of swimmers, surfers and divers.

Sea Life Sydney marine biologist Marty Garwood said available data shows shark numbers are at "historically low" levels, mostly due to overfishing and sharks being caught inadvertently before being deposed of as so-called "by-catch".

He also said attacks this year in NSW were an "unusual blip" - similar to numbers seen recently in Western Australia.

Great white sharks among others species are widely blamed for attacks on humans

Regardless of the so-called blip, experts warn that some sea-lovers will always be more vulnerable to shark attacks than others.

"Surfers and divers tend to use the water a little further out from the coastline," Mr Garwood said.

"Surfers in particular have a silhouette from underneath that sometimes looks similar to a seal or a turtle - so a great white might be checking out whether it is a turtle or a seal," he explained.

"And that initial bite is what does so much damage to those unfortunate surfers who happen to be in the wrong place at the wrong time."

Life changing

Former army paratrooper and navy clearance diver Paul de Gelder is now a motivational speaker

On February 11th 2009, Paul de Gelder's life changed forever.

The former army paratrooper and navy clearance diver was taking part in a counter-terrorism drill in the waters of Sydney Harbour when his hand and most of his leg were ripped off by a 2.7m shark.

"I was swimming along the surface when a bull shark came up from underneath me, grabbed me, and tried to kill me," he told the BBC.

"When the shark actually bit me it didn't hurt. It felt like someone had just hit me in the leg with a cricket bat.

"So I really didn't panic that much until I looked down and saw this monstrous shark's head attached to me. The pain only kicked in when it actually started to shake me - and then I can't even describe to you how painful it was. It was the most horrific thing I've ever felt in my life."

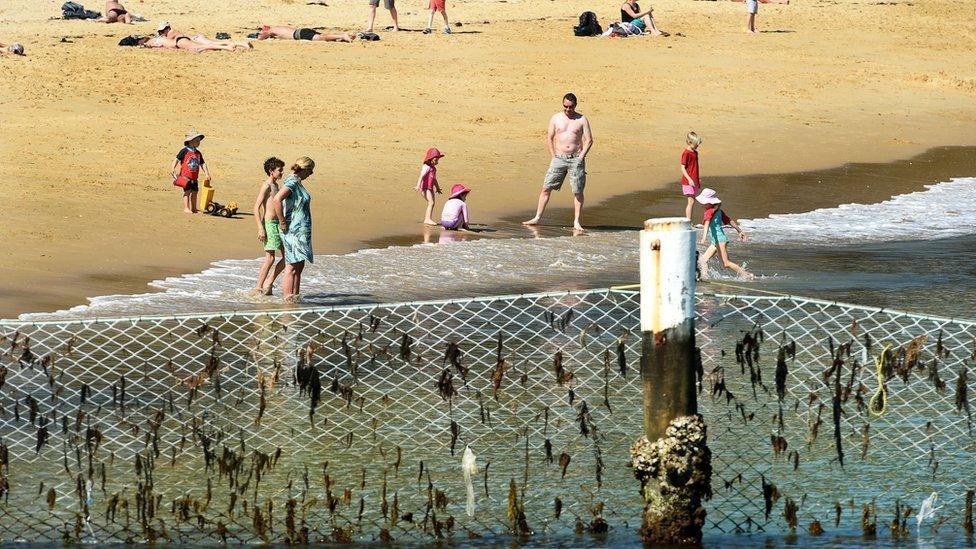

Detect and deter

Shark nets are used on many beaches in Australia

Some 70 shark experts from around the world met in Sydney last month as part of a government review into shark deterrent and detection technology.

Some of the technologies discussed included electric and magnetic barriers, flexible plastic nets and phone apps that could allow real-time tracking of tagged sharks.

Current defences include a system of netting used at more than 50 beaches in NSW, aerial patrols and monitoring by surf lifesavers.

But Dr Vic Peddemors, principal shark scientist for the NSW state government, told the BBC that more effective protective measures are needed.

"(The) risk of a shark attack is extraordinarily low, but unfortunately it is a very traumatic event and it really has a massive impact not only on the victim, but the victim's family and any witnesses on the beach," he said.

"It also hits local economies and tourism. There are several places around the world whose economies rely heavily on tourism - and they have seen major downfalls as a result of [shark attacks]."

- Published29 September 2015

- Published20 July 2015

- Published31 August 2015

- Published10 April 2014