Australia's anti-Islam movement seeks Geert Wilders touch

- Published

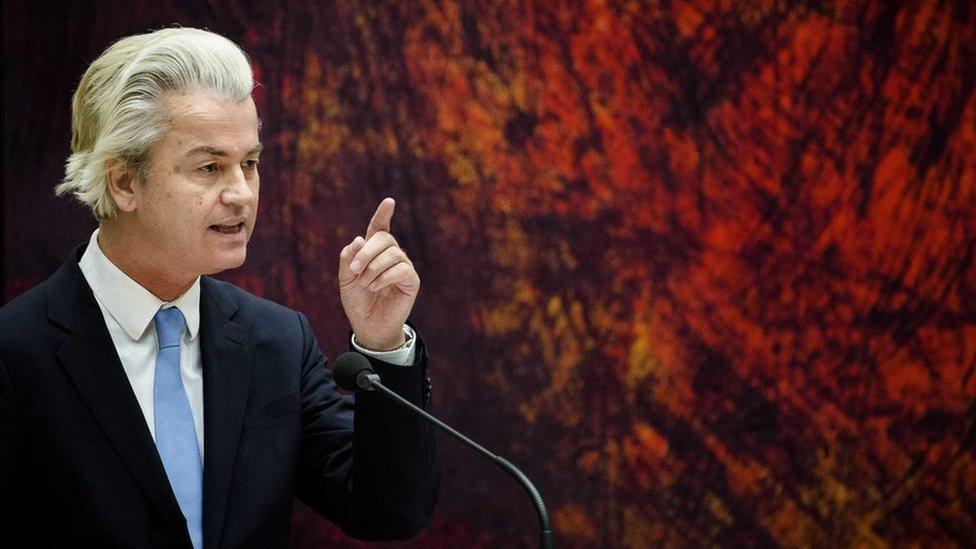

Mr Wilders has called Islam an "inferior culture" and wants the Koran to be banned in the Netherlands

No press, and it's invitation-only to an event at an undisclosed location in Western Australia, attended by one of the democratic world's most divisive politicians.

On Tuesday, Geert Wilders, controversial leader of the right-wing Netherlands' Party for Freedom, will be the keynote speaker at the launch of the Australian Liberty Alliance (ALA).

Its manifesto states that "Islam is not merely a religion, it is a totalitarian ideology with global aspirations".

Australia's newest political party wants to curb Muslim immigration.

Secretive launch

Speaking to the BBC from Perth, the ALA's Scottish-born president Debbie Robinson insisted that Islam was having a corrosive effect on many countries.

"It is dangerous for any Western society in that it is divisive and it promotes parallel societies," she said. "People are looking for an alternative because the major parties are not prepared to discuss some of the issues: the divisiveness of multiculturalism and the damage that is being done to Australia."

Little is known about Tuesday's secretive launch, perhaps unsurprisingly, given Mr Wilders' presence.

The West Australian Premier Colin Barnett has refused to allow the event to take place at any state government venue, while Muslim groups are divided over whether Mr Wilders should be allowed into Australia, which recently banned US rapper Chris Brown for his criminal convictions and deported the American anti-abortion activist, Troy Newman.

Malcolm Turnbull has said extremism of all kinds is a threat to Australian values

Mr Wilders' visit comes at a sensitive time, just over a fortnight after a 15-year old Muslim boy shot dead a police accountant in Sydney. As Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull was calling an emergency summit to address the radicalisation of the young, the head of the Australian Federal Police warned that the threat of domestic terrorism was getting worse.

But Mr Turnbull has also warned that those who vilify all Muslims for the acts of the few "are absolutely acting in a thoroughly counterproductive way".

Anti-Islam demonstrations have also drawn counter-protests by anti-racism activists

'Minimal impact'

Kuranda Seyit, the secretary of the Islamic Council of Victoria, said the principles of free speech should allow the Dutchman to come.

But he told the BBC that although he considered the ALA to be a fringe group, he was wary of its views on Islam.

"Relatively speaking they are small and their impact on social cohesion will be quite minimal. However, similar to a mosquito, once it bites you it can be quite irritating and can turn into a rash," he said.

"So we need to be careful and vigilant about this because we don't want them to grow or spread."

Few Australian ultra-conservative parties, like Pauline Hanson's One Nation group, have had lasting electoral success

Far-right politicians in Australia typically fail at the ballot box.

There are some exceptions, most notably Pauline Hanson, a flame-haired former fish-and-chip shop owner from Brisbane whose anti-immigration One Nation Party had some successes in the late 1990s, winning 22% of the vote in a Queensland state election.

But it soon went sour. Public support waned, and in 2003 Ms Hanson went to prison for electoral fraud, although her convictions were overturned on appeal.

Duncan McDonnell sees Australia's right-wing parties as "rabble-rousers at best" with limited potential for electoral success

Duncan McDonnell, a senior lecturer at Griffith University in Brisbane, believes the current crop of far-right groups have little chance of electoral success.

"They don't have the type of charismatic leaders that most European radical right parties that have been successful have got," he said.

The Australian Liberty Alliance became a registered party in July and does have parliamentary ambitions, but hasn't divulged the strength of its membership, saying only that it was "growing steadily".

"This party derives from an anti-Islam organisation called Q Society," Mr McDonnell explained. "It has tried to model its policy platform very much on what Wilders has done in the Netherlands with the Party for Freedom."

"These aren't particularly articulate or capable people. They are rabble-rousers at best," he added bluntly.

They are not the only organisation on the far-right political fringe, which includes Reclaim Australia and the United Patriots Front, who recently held a protest against the building of a mosque in the Victorian town of Bendigo.

Nick Folkes, the chairman of the Party for Freedom - which has no formal link with its Dutch namesake - also campaigns against what he describes as the islamisation of Australia.

"It's crazy. We are losing our identity," he told the BBC News website. "I don't think we are racist at all, and we have a right to speak up and say we're not happy with the government."

Sensitive timing

To some, Geert Wilders is a hero, to many others he is dangerous and divisive.

Frank Mols, a lecturer in political science at the University of Queensland, went to the same high school as the Dutch MP, and believes his visit to Perth is designed to impress voters back home in the Netherlands.

Australia's own Party for Freedom says the country is "losing its identity"

"Partly the reason is to get credibility [and] the fact that he is invited overseas is one way he can show the domestic audience that he is reputable man who has a reputation worldwide for what he believes in," said Mr Mols.

Despite the urgings by the government in Canberra, a tendency persists in certain quarters to link all of Islam with extremism.

Franks Mols has warned that far-right groups will increasingly try to exploit community tensions.

"Certainly given the attention at the moment to terror plots and suspects, and laws about whether younger and younger people have to be monitored or detained is adding to that general anxiety that those parties will tap into," he said.

It's unclear if Geert Wilders's visit will provoke protests in Perth, but Australia will be wary of the divisive views he brings at a time when the nation tries to both handle an increasingly vocal Islamaphobic element and to work out how to stop marginalised young Muslims falling prey to extremism.

- Published24 June 2014

- Published9 October 2015

- Published4 October 2010

- Published23 June 2011