Is it right to take wild crocodile eggs?

- Published

Farm-reared crocodiles products can fetch a high price, but critics say the cost to the species is too high

It is the stuff of Boys' Own adventure novels - rugged Australians dropping into wild saltwater crocodile nests to snatch day-old eggs from territorial females.

The eggs command a high price from farms which produce meat, leather and other goods, so there are plenty of people willing to take on the risky job.

But whether this derring-do should be legal or not has become a hot topic in the state of Queensland, where the government is reviewing its crocodile management plan.

Proponents say legalisation in the neighbouring Northern Territory brought substantial economic benefits, particularly to indigenous communities, without affecting crocodile numbers.

Critics, though, say it is not right to take the eggs, as most are already lost to inundation or predation.

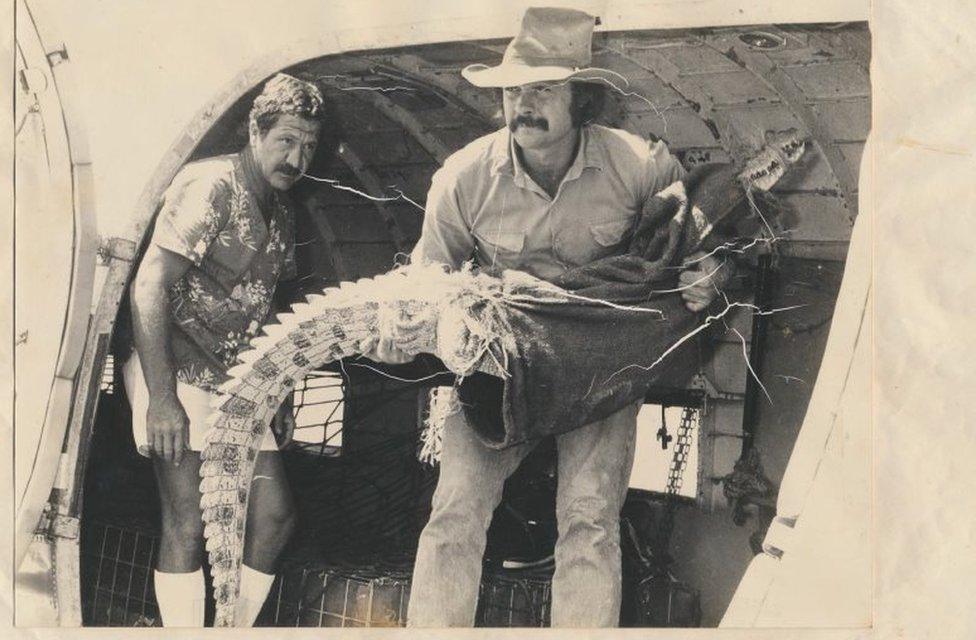

John Lever (right) started Koorana, the first commercial crocodile farm in the north-eastern state of Queensland

'Emotional claptrap'

Leichhardt Federal MP and former crocodile farmer Warren Entsch says few people understand the crocodile industry and "it's easy to bring emotional claptrap".

He told the BBC he strongly supports legalising egg harvesting in Queensland.

He would like to see a quota of eggs taken from nests, harvested, then sold to farmers who supply skins to global fashion houses.

Mr Entsch said the number of saltwater crocodiles in the Northern Territory had grown substantially despite the provision for egg harvesting, with current estimates putting their population at around 100,000.

"Now there are more crocodiles [in the Northern Territory] than before when the 'white fella' came to Australia," said Mr Entsch.

"The proliferation of the crocodile is huge and that in itself is causing a few problems."

But conservationists say only a few crocodiles reach maturity in the wild and removing eggs could have a devastating impact.

Animal activists pose in front of a Hermes store in Sydney

"We're playing God to a degree, there's a reason why their [survival rates] are so low, because only the strongest fittest baby will survive," Australia Zoo crocodile research team leader Toby Millyard said.

The wild world of crocodile farming

Liberal National MP Warren Entsch (centre) said the pilot would not get out of the cockpit until all of the reptiles were offloaded

Warren Entsch said one of the more unusual encounters he had while crocodile farming was during a flight over Queensland in the 1980s.

He was forced by the pilot to travel in the cargo bay alongside a bigger-than-expected haul of crocodiles. Three were tied up and covered with hessian bags because Mr Entsch miscalculated the number of transportation cages.

He told the BBC he was given a loaded handgun and warned not to shoot the fuel tank if the crocodiles escaped their makeshift restraints.

The animals became ill due to altitude sickness, leading them to vomit and defecate throughout the plane. "They went ballistic," Mr Entsch recalled.

Crocodile farmer John Lever, from Koorana in Queensland, has been on multiple trips to gather eggs from crocodile nests.

The 63-year-old said he had some close calls with crocodiles, but "it's a bit like having a near miss in your car, you go off and forget about it".

"You learn to manage behaviour about the nest, but when a big male challenges you at night and you're on a little boat on the river in the dark that can be pretty intimidating when they're 5m (16ft) and three quarters of a tonne (750kg)," Mr Lever said.

The estuarine crocodile is protected as a vulnerable species under current Queensland legislation, a point of conjecture on both sides of the debate.

The state government says it will only back the egg harvesting plan if it does not threaten the animal's survival in the wild.

Mr Millyard said accurate surveys of crocodile populations had not been conducted for a decade and needed to be completed before a decision was made.

"Anything people say about crocodile numbers is really hearsay and opinion," he said.

Veteran Kakadu Park Ranger Gary Lindner told an inquest last year into the Bill Scott, 62, that a "she'll be right" attitude may have contributed to crocodile attacks in Northern Territory waterways

Egg harvest trial

The final report into a trial live egg collection trial in Cape York - the largest and most intact tropical savanna left on Earth, external - is expected to be released by the Queensland Government in the coming weeks.

Robbie Morris, environmental manager of Pormpuraaw Aboriginal Shire Council in Cape York, said the study has shown there would be no impact on populations if a limited harvest of wild eggs are taken from nests that would already be washed away by flooding.

"Wild eggs could be taken and hatchlings reared without influencing the population," he told the Cairns Post., external

"If we do actually get the go ahead to do a wild egg harvest there would be scope for three or four permanent positions at the farm for local indigenous people."

The Australian Conservation Foundation's Andrew Picone said a range of issues needed to be considered before allowing egg harvesting in Cape York.

"At face value it presents some problems [but] if there's not any economic opportunities on the Cape [York] things like mining and other extractive industries will continue to be seen as the only option, and undermine tourism," Mr Picone told the BBC.

Fashion houses buying crocodile farms

How do you harvest wild crocodile eggs?

Wild crocodile eggs are valuable because when raised in captivity the reptile's skin is more likely to be unblemished.

The eggs are removed from wild nests by one person, while another distracts or stands guard against the mother crocodile.

Part of the grass nest is placed in the base of an "esky" or cooler bin before the eggs are carefully placed in the exact formation as the original nest.

The heat generated from the nest is key for survival and also determines the sex of the animal, so meticulous arrangement of the eggs is vital. "If you turn the egg the embryo will die", Koorana crocodile farmer John Leaver says.

The egg is then washed to kill fungal spores and incubated for about 83 days.

He agreed that expanding the farming industry in Queensland could also provide culturally appropriate opportunities for remote indigenous communities.

Northern Territory expansion

Meanwhile, the Northern Territory recently increased the number of eggs that can be harvested each year by 40% to 90,000 viable eggs.

Its Wildlife Trade Management Plan also allows for the take of 1,000 live crocodiles.

The government aims to double its crocodile products industry to A$50m ($35m; £24m) in four years.

- Published14 January 2016

- Published3 December 2015