Fearsome Australian 'lion' could climb trees, study says

- Published

An artist's illustration of Thylacoleo carnifex, Australia's marsupial lion

The discovery of claw marks in a bone-filled cave in Australia suggests an extinct, "anatomically bizarre" predator was able to climb trees and rocks, meaning it would have been a threat to humans, writes Myles Gough.

Australia's extinct marsupial lion, Thylacoleo carnifex, was the continent's top predator at the time of human arrival 50,000 years ago.

Weighing more than 100kg, the animal had sharp claws and a powerful jaw, and shearing teeth that could rip through the flesh of its prey, which included giant kangaroos, rhinoceros-sized herbivores known as diprotodon, and possibly humans.

But while experts agreed on the marsupial lion's fearsomeness, whether or not they could climb rocks and trees has been a source of contention.

Some speculated that the lions' anatomy would lend itself to climbing, while others argued they would have been too heavy to clamber up to high places.

Now palaeontologists at Flinders University say they have found the answer in a cave in Western Australia where marsupial lions left thousands of scratch marks.

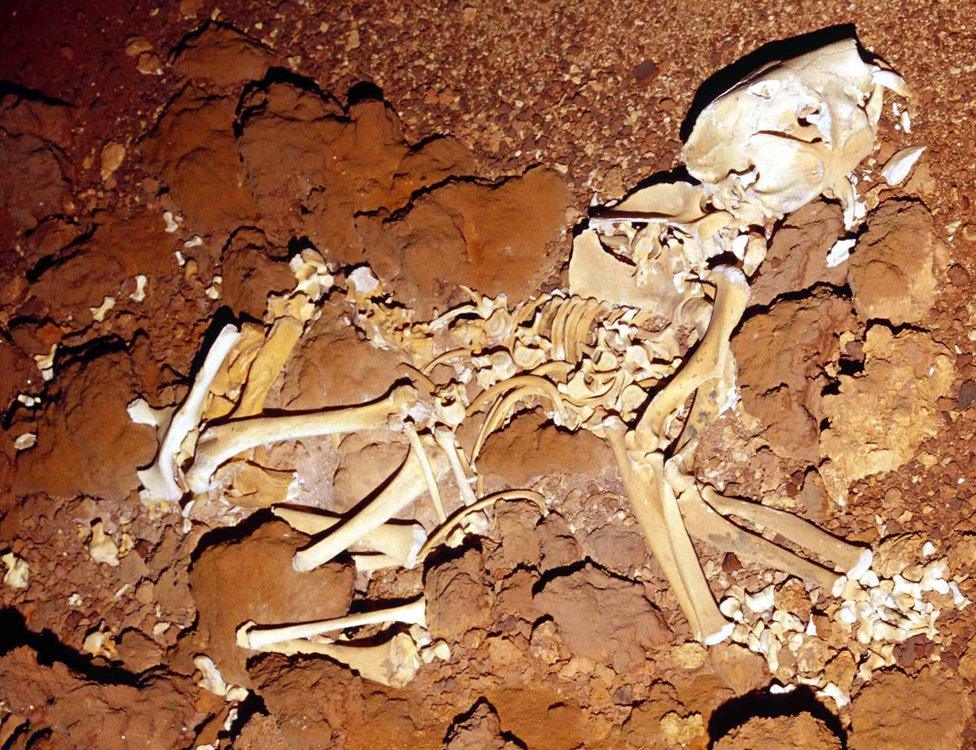

A reconstructed skeleton of the marsupial lion, which weighed up to 100kg

'Significant threat to humans'

The scratch marks, mostly made by juveniles and clustered on a near-vertical rock surface leading to a now-sealed exit, suggest two things about the lions: they were skilled climbers, and they reared their young inside caves.

"[Our findings indicate] the [marsupial] lions were running up and down these rock piles to get out of the cave, and they weren't using the lower-gradient, longer route," says associate professor Gavin Prideaux, who supervised the research.

"We can be confident now and say that they could climb.

"And if they could climb really well in the dark, underground, there's no reason they couldn't climb trees.

"They would have been a very significant threat to people when they first arrived in Australia.

"What we're dying for are different lines of evidence that shed light on the behaviour or ecology of these animals, and that's what we've been presented with in the form of these claw marks."

The team's findings, which reinforce some contentious ideas about the behaviour of these "highly adapted" and "anatomically bizarre" predators, have been published in Nature's open-access journal Scientific Reports.

Identifying the scratch marks

An almost complete skeleton of a marsupial mammal was discovered inside Western Australia's Flightstar Cave

The claw markings were found inside the Tight Entrance cave near the Margaret River.

In the mid-90s, bones inside the cave were identified as belonging to extinct megafauna, dating from 30,000 to 150,000 years old, says Prof Prideaux.

Between 1996 and 2008, he went on numerous expeditions to the cave to collect fossils, and during that work discovered the scratch marks.

"We had the feeling that they were probably Thylacoleo scratch marks, but we had to test it," he says.

Prof Prideaux and his honours student, lead author Samuel Arman, established a list of seven species of animal that could have been responsible.

It included the extinct marsupial lion, as well as Tasmanian tigers and Tasmanian devils, which used to live on the mainland, wallabies, koalas, possums and wombats.

Mr Arman left scratch pads inside zoos and wildlife parks, and collected tree bark to get sample claw markings from the living animals, which he compared to those inside the cave.

Lions and devils

This helped the researchers narrow their list to two key suspects: marsupial lions and Tasmanian devils. But they needed another clue.

Zoo tests helped the scientists rule out Tasmanian devils as being behind the scratches

"We went through the more than 10,000 bones we collected from the cave to look for evidence for bite marks or little chewed-up bones [which are] absolute hallmarks of devil dens," says Prof Prideaux.

"We found zero of that."

"This is more consistent with what we've inferred about the behaviour of Thylacoleo from its dental morphology, and that is, it was primarily a meat eater and not a bone cruncher."

Mr Arman also reconstructed a skeletal hand of the marsupial lion and made mock scratches on modelling clay that "perfectly matched" the large ones found in the cave.

The animals, which became extinct around 46,000 years ago, lived all across the continent. Prof Prideaux suspects similar claw markings exist in caves elsewhere, but have yet to be discovered.

Dr Judith Field, an expert in megafaunal extinctions from the University of New South Wales, says "the methods used to determine the size of the animal making the marks appear well conceived and well executed".

"It is highly likely these marks were made by Thylacoleo," she told the BBC. "They are probably the only animal with claws large enough to effect these scratch marks."

Still, Dr Field expressed some reservations about the study: "Most of the conclusions are speculation," she said. "Great discovery, and a neat story, but these assertions about their behaviour have yet to be substantiated by empirical data."