Key issues in Australia's early election

- Published

There is a clear policy gulf between Australian Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull (centre left) and Opposition Leader Bill Shorten (centre right)

Australian Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull confirmed on Tuesday his intent to dissolve parliament and hold an early election on 2 July.

This sets the scene for a mammoth election campaign that unofficially begins now, 74 days out from the proposed poll date.

It's early days but already a number of policy and leadership themes are emerging. Mr Turnbull's decision to call a double dissolution election has ramifications for Australia's upper house, the Senate, too.

What is a double dissolution election?

Australia's constitution allows, external for an early election to be called when the upper house, called the Senate, twice blocks a piece of legislation that has been passed by the lower house, the House of Representatives. Although ostensibly designed to resolve political deadlocks, in practice it has largely been used opportunistically by governments who see an advantage in going to the polls early.

The rejected legislation in this case is the Australian Building and Construction Commission (ABCC) bill, which seeks to re-establish a watchdog to monitor union activity in the construction industry. Although the government is insisting the bill is important enough to warrant calling a double dissolution, the opposition and most pundits believe that the decision is more about politics than policy.

What are the key policy battlegrounds?

Both sides will reveal their platforms over the coming weeks, but the broad campaign brushstrokes are already there to see.

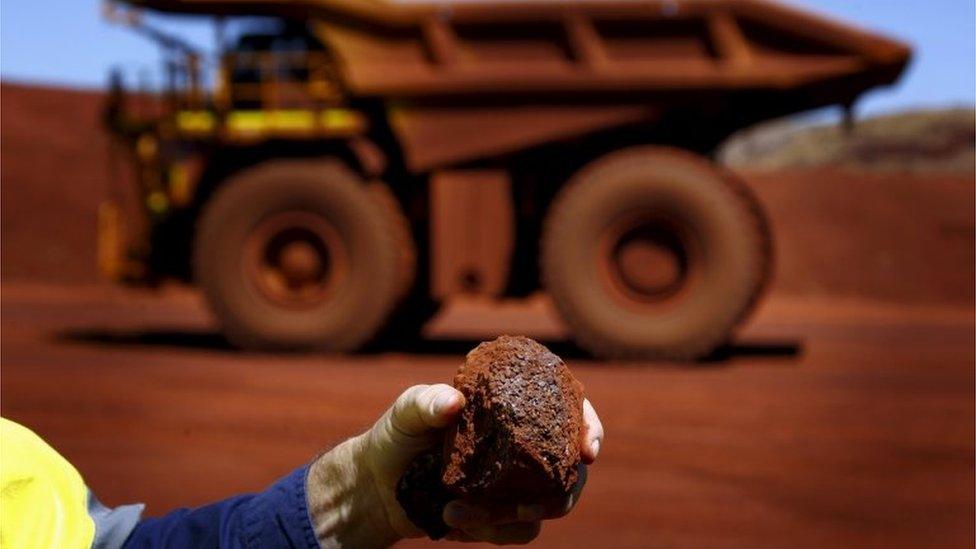

The future of Australia post-mining boom will likely feature high in voters' minds

The government will centre its campaign on economic management credentials. It will position itself as the party best placed to transition Australia from the mining boom through to a new phase of economic growth.

Even its attack on the unions with the ABCC bill is being framed as an economic issue and this line of attack will likely fall away as the campaign progresses. The 3 May budget will provide clarity on the government's economic plan.

Labor, conversely, will run on a "people first" platform of health, education and nation building, while also making cost savings in the budget. Opposition Leader Bill Shorten is also lobbying hard for a Royal Commission into banks.

How do the leaders stack up?

Despite operating under the Westminster system, Australia's election campaigns tend to have a presidential flavour. So the popularity of the prime minister and opposition leader will be a key factor in determining the winner.

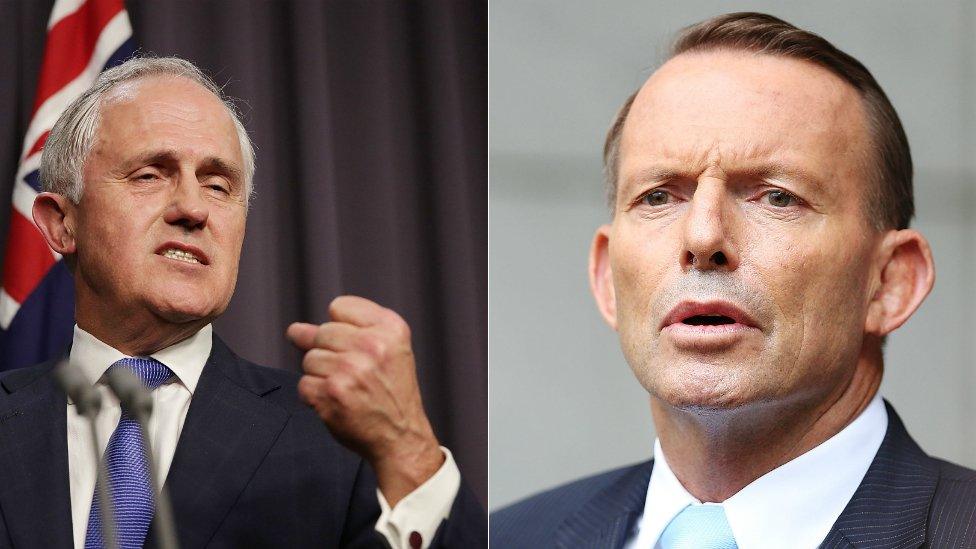

Mr Turnbull's popularity with voters made it politically feasible to oust Tony Abbott

Mr Turnbull is the clear frontrunner here. Well known to Australians through his prominent public life as a barrister and advocate for the republic movement, he maintains a handy lead over Mr Shorten as preferred prime minister. It was Mr Turnbull's popularity with the electorate that prompted the Liberal party to dump Tony Abbott as its leader.

But Mr Shorten has narrowed the gap on his opponent over recent months and at this stage appears to be running a more disciplined campaign. He'll need to prove himself against Mr Turnbull in one-on-one debates later on, but the seasoned parliamentary performer is used to such public forums.

Mr Turnbull will attempt to paint Mr Shorten as a union lackey who cannot manage the economy; Mr Shorten, conversely, will say Mr Turnbull is an out-of-touch protector of greedy banks leading a divided party that stands for nothing.

How many seats does Labor need to win?

Labor needs to win 21 seats to take power, a swing of 4.3%. Recent polls have Labor in a position to achieve a swing of this magnitude on a two-party preferred basis, but the reality is more complex than that.

Mr Turnbull could pull more preferences from the Greens than more conservative leaders and individual battles in key marginal electorates are likely to have a big impact on the result. Labor's primary vote remains very low.

What about the Senate?

The government passed laws changing how Australians vote for members of the upper house in March. The new rules change the distribution of preferences in such a way that members of so-called "micro-parties", such as the Motoring Enthusiasts Party, will find it much more difficult to secure seats in the Senate. A double dissolution election requires that all Senate seats be declared empty - at a normal election, only half of the seats are up for grabs, and Senators typically get two terms in office.

The chance to get rid of pesky crossbench senators who block government legislation and secure a majority in the upper house is clearly one of Mr Turnbull's motivations for holding the double dissolution. But with opinion polls moving against him, it remains to be seen whether the prime minister's gamble pays off.

- Published19 April 2016

- Published14 September 2015

- Published21 March 2016

- Published14 September 2015