The gay Anzacs who refused to stay silent

- Published

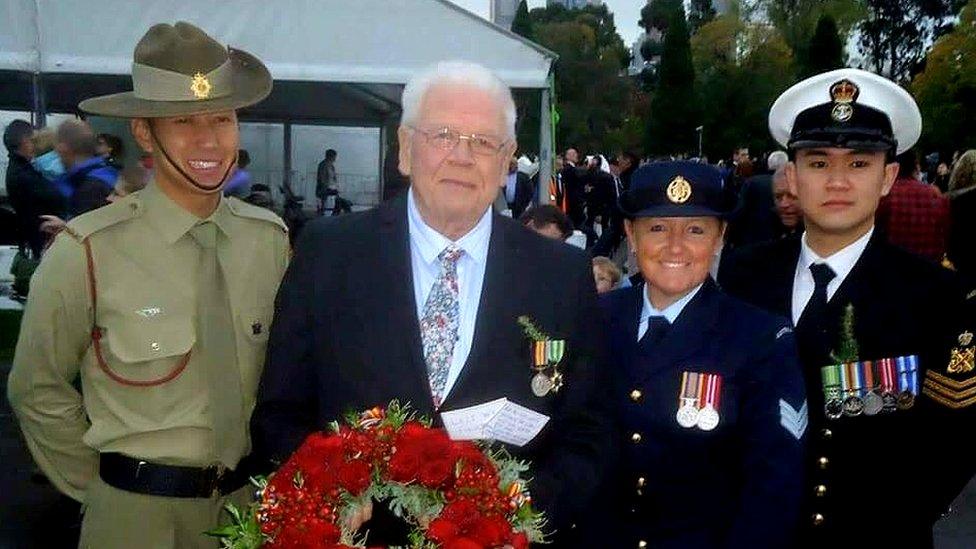

Max Campbell (pictured centre left) was not allowed to lay a wreath on behalf of gay ex-servicemen in 1982

Stuart Martin looks back with pride on his six years as a nursing officer in the Royal Australian Air Force. But he also recalls having to "not be gay". And one incident from that era sticks in his mind: a veterans' leader physically blocking a group of gay ex-servicemen trying to lay a wreath during an Anzac Day service.

It was 1982, and the man obstructing them was the notoriously bellicose Bruce Ruxton, long-time president of Victoria's Returned and Services League. On Monday, as Australians remember their war dead at Anzac Day ceremonies, Mr Martin - health permitting - will be among current and former military personnel placing a rainbow wreath at that same shrine in Melbourne.

The service and sacrifice of gay and transgender members of the Australian Defence Force (ADF) will be similarly honoured at ceremonies in Sydney, Canberra, Adelaide, Brisbane and Townsville - thanks largely to Mr Martin, who decided last year that it was time to "address an injustice" and "acknowledge all those who have gone before us".

That the ADF has given its blessing to this new Anzac Day tradition is testament to how much things have changed since Mr Martin's day, when military police would "hang about gay nightclubs looking for people with very short haircuts and take pictures of them to compare with the military files," he recalls.

Rainbow wreaths were laid in cities around Australia at last year's Anzac centenary

Back then, as elsewhere, gay people were still barred from joining the armed forces.

Mr Martin says: "I was prepared to be quiet about it, but there was always that worry at the back of your mind, and many people I knew had a terrible time. Military police were doing a lot of undercover work rooting out gay people and with the emergence of HIV/Aids the witch hunts intensified. That was the climate at that time."

Those who were outed were given the choice of receiving a dishonourable discharge or resigning, according to Dr Noah Riseman, an Australian Catholic University historian researching marginalised groups in the military. Most chose the latter and from then on were unable to march with their units in Anzac Day parades.

'Stand up, be visible'

Max Campbell, who was in the Air Force for 20 years and subsequently formed the Gay Ex-Services Association (GESA), led the 1982 attempt to lay a wreath, along with a card stating: "For all our brothers and sisters who died during the wars."

Mr Ruxton accused him and his comrades of "denigrating" Anzac Day, declaring: "I don't mind poofters in the march, but they must march with their units... We didn't want anything to do with them."

Last year, on the centenary of Australian troops landing at Gallipoli, and on "one of the best days of my life", as he called it, 71-year-old Mr Campbell proudly placed a rainbow wreath at Melbourne's Shrine of Remembrance. Accompanying him was Mr Martin, who had instigated the push for gay personnel to be included in Anzac Day ceremonies.

Stuart Martin (left) pushed for the recognition of LGBTI servicemen and women during Australia's Anzac remembrances

The Victorian coordinator for a group that succeeded GESA, the Defence Gay and Lesbian Information Service (DEFGLIS), Mr Martin says: "It's about righting a wrong for all those people who served silently, and saying to all those veterans out there that you can finally stand up and be visible and play your part in Anzac Day.

"It's also about raising awareness that there's a history of LGBTI service in the ADF and of people sacrificing their lives. We existed then, we exist now, and we no longer need to hide."

Although the ban on gay servicemen and women was lifted in 1992, the ADF's culture has changed only gradually. It was not until 2005 that family benefits were extended to same-sex partners, while a prohibition on transgender people in the military was abolished only in 2010.

Now the Defence Force actively targets gay recruits, and high-ranking members such as Air Vice Marshal Tracy Smart and Group Captain Cate McGregor, the world's most senior transgender military officer, enjoy a high profile.

At last month's Sydney Gay and Lesbian Mardi Gras, 140 Army, Air Force and Navy personnel marched in uniform. In September, DEFGLIS will organise its second Military Pride Ball.

There have been bumps along the way. In 2011, for instance, Jim Wallace, a former SAS commander and head of the Australian Christian Lobby, caused outrage with an Anzac Day tweet expressing hope that "as we remember servicemen and women today we remember the Australia they fought for - wasn't gay marriage and Islamic!"

Pockets of homophobia persist within the military itself - as Dr Riseman notes, the institution is bound to reflect the spectrum of opinion in civilian society.

However, gay people can now "serve openly and without fear", says former Army officer and DEFGLIS secretary James Montague Smith, paying tribute to the courage and hard work of Mr Campbell and his comrades.

- Published17 April 2015

- Published1 November 2014

- Published26 April 2015