Viewpoint: Why fake news is a story we all share

- Published

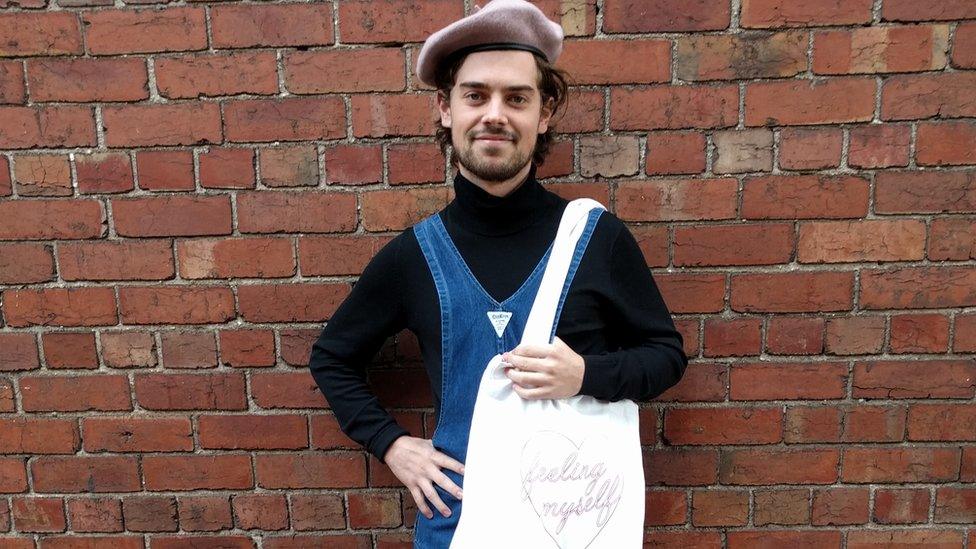

Melbourne man Sam Hains was branded "the world's biggest hipster" after his fraudulent profile appeared in a newspaper

In the race to compete with viral media sites, fake stories contaminate the output of once-reputable news publishers. But stories that are too good to be true predate the internet, writes journalist and hoaxer Matt Thompson.

Samuel Davide Hains was a beguiling man - at once silly, radical and self-assured.

He wore second-hand overalls backwards, carried a tote bag emblazoned with the slogan "Feeling Myself" and professed to admiring "the style of Trotsky in leather".

"My favourite place to shop is K Mart," he said. "I like to re-imagine chain store garments and pair them with high end fashion, like my Chanel cape."

The editors of Melbourne's The Age found Samuel's off-beat shtick so intriguing that they put him on the newspaper's website, external and the front page.

Soon he was dubbed "the world's biggest hipster" and his absurd interview rocketed around the internet, spawning scores of follow-up stories and millions of clicks.

But Samuel Davide Hains didn't exist. He was a hoax, perpetrated by Sam Hains, a computer programmer with a talent for making absurd statements on the fly.

Genuine fake

Hains, 24, admitted to VICE, external that his bucolic-socialist-with-a-dash-of-jazz persona was a hoax. The Age has since fired Tara Kenny, external, the journalist who knowingly submitted Sam's lies to the Street Seen fashion column.

Hains described the "media machine" that chased him as "diabolical", saying that "the whole thing was getting out of control". He found the level of abuse he copped "saddening and disturbing".

Online comments ranged from potty-mouthed sledges to a patriotic Daily Mail reader's suggestion that "the diggers in Gallipoli (where Australians fought in World War One) would be shaking their heads in disbelief".

Digital vitriol is now so prevalent that it has become a respectable area of study, with Scientific American running such articles as 'Why Is Everyone on the Internet so Angry?, external' Hains' playful foppishness surely landed him squarely in the terrain where clickbait and frothing hate are intimately entwined.

But while it's tempting, can we really say that Hains' deception and the media tsunami that followed are part of some digital culture zeitgeist?

What if naïve and absurd "churnalism" is not new at all? And what if going for the jugular is a human evergreen?

Rightly or wrongly, Melbourne is widely regarded as the hipster capital of Australia

T-shirt terror

Back in the primordial, parochial year of 1992, a bizarre and revealing media frenzy swept Australia - that of Young People Against Heavy Metal T-Shirts (YPAHMTS).

I founded YPAHMTS by accident one morning while working in a Sydney office where the boss forever had talkback radio booming. A prominent Australian shock jock, Alan Jones, was banging on about a local thrash-punk band called the Hard-Ons. Jones said the group's name was symptomatic of a youth culture's moral decline.

Jones bugged me, so to let off steam I knocked out a letter claiming to be the head of a growing national movement called Young People Against Heavy Metal T-Shirts and faxed it to a few newspapers. Here's a snippet of my earnest drivel that "went viral":

Young people have shown remarkable responsibility towards the environment, and now it is time for them to clean themselves up and act with equal respect for themselves and their elders.

This means stopping socially and personally damaging activities such as smoking, drinking, swearing, taking drugs, easy sex and, in particular, wearing heavy metal T-shirts.

Heavy metal T-shirts may seem like a small issue, but look at how many people wear them in public. They depict scenes of violence and sex, and in many cases openly incite subversion and a cynical attitude towards the moral guardians of our society, such as the police, parents, religious figures and law and order in general.

Matt Thompson led a fraudulent campaign against heavy metal T-shirts in the 1990s

Media machine

It seemed too ludicrous to be published, but a couple of days later my boss slapped down the Daily Telegraph, Sydney's tabloid newspaper, opened to a page with the bold headline: 'Stamp out T-shirt terror'. As he demanded to know what the hell this was about, the phone rang.

It was a journalist, wanting to interview me, the first in a string of calls from print, radio and television reporters. All asked which other outlets I had spoken to - the competition was fierce.

I ad-libbed answers, claiming to have about 50 members across a few states. No-one checked anything, not even when I decided to up the weird stakes and say on national TV and radio that I would be running a series of youth camps in the desert.

This was at a time when journalist Derryn Hinch, who will almost certainly be moving into the upper house of Australia's parliament this year, had a high-rating current affairs TV show called Hinch.

The Hinch producers wanted to film a YPAHMTS meeting, so I roped in friends to play a range of stereotypes (a woman complaining of the T-shirts' misogyny; a yuppie; a very positive-minded ethnic Australian; a former metal head who used to wear the shirts but met me and saw the light).

Dial-up

In some ways, the pre-internet era was even easier to work a con; when a radio producer from Australia's national broadcaster, the Australian Broadcasting Corp. (ABC), said he'd be interested in seeing one of our newsletters, I just whipped up something duly quasi-fascist and backdated it.

The ABC was my best customer, giving me substantial platforms on networked AM radio, youth station Triple J and even television. My followers and I were invited to Melbourne for an edition of the well-regarded Couchman chat show.

My technique was to keep out-manoeuvring interviewers and talk-back callers by refusing to be what they expected. To accusations that I must be a fundamentalist Christian, I answered that I was a "socially active Taoist". One essential problem of the offending T-shirts, I said, was a mindset of "labelism". After my Triple J appearance, I received letters from people wanting to join YPAHMTS or start a local chapter. Interest was especially strong in Adelaide.

I was stopped in the street and copped many fierce salvos. One radio caller memorably threatened to strangle me with my mother's blood-stained panties. People are like that.

So I don't think of ridiculous stories, mass gullibility and poisonous sledging as part of some expression of the viral media zeitgeist. To me, they seem like long-standing aspects of the human condition - the delivery mechanism has changed but fake stories remain as disingenuous as ever.

Dr Matthew Thompson is an author, journalist and academic.

- Published1 June 2016

- Published31 August 2015

- Published19 July 2015