Australia PM's nasty case of second-term slump

- Published

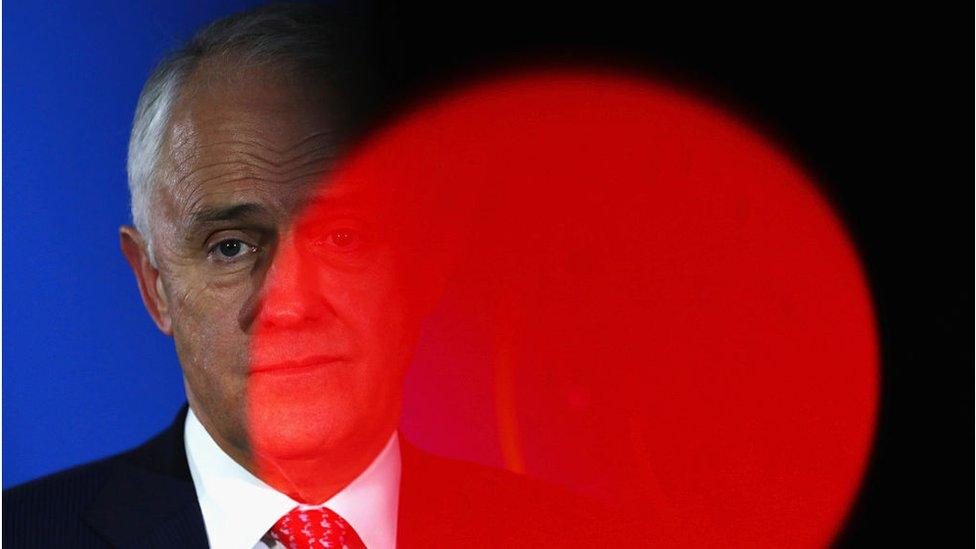

Critics are targeting Malcolm Turnbull, Australia's prime minister, after a poorer-than-expected showing at Australia's election

Critics have lined up to kick Australian Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull after the conservative Liberal-National coalition's narrow election victory.

On 2 July, the night of the election, ultra-conservative commentator Andrew Bolt was first out of the blocks, telling Turnbull bluntly: "Resign."

"You have been a disaster," Bolt wrote. "You betrayed (former PM) Tony Abbott and then led the party to humiliation, stripped of both values and honour."

Opposition leader Bill Shorten spent last week gleefully calling Turnbull a "prime minister with no authority" and predicting Australians would be back at the polls within a year.

Australia PM Turnbull's conservatives win tight election

But while things look chaotic from close-up, Australia's recent political history suggests this is business as usual. Turnbull is suffering from a political malaise that's common "down under" - the second-term slump.

'Don't slit your throat'

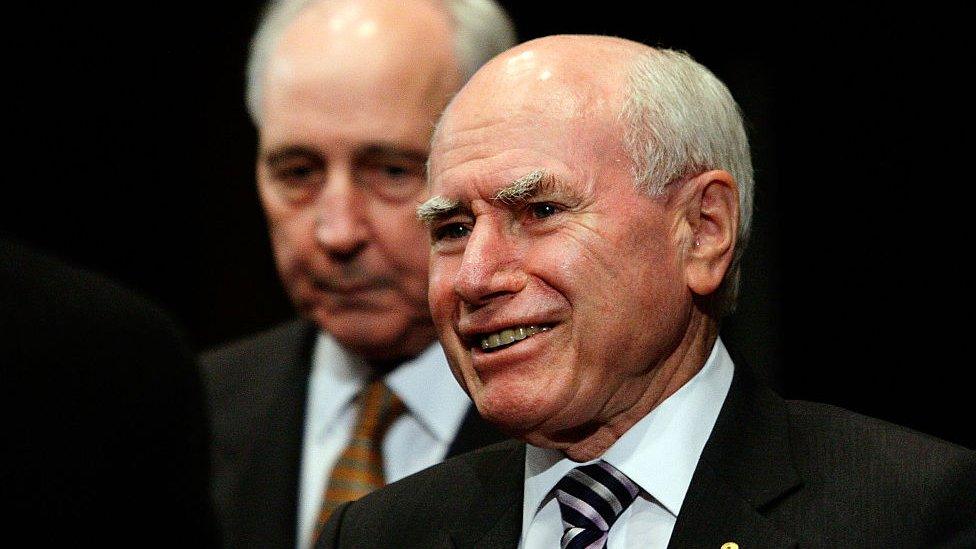

Amidst the rancour and heated denunciations last week, former prime minister John Howard offered a much cooler assessment of the government's performance and Turnbull's leadership.

"This hasn't been an outcome that we wanted, but it's not the end of the world and people shouldn't start slitting their throats," he said.

Howard knew this from experience - he, too, suffered from second-term slump.

Former Australian leader John Howard barely won a second term at Australia's 1998 election

In 1996, he took the conservatives to their first election victory since 1983 in a massive win that gave them a majority of 45 seats.

But in 1998, Howard broke a promise to "never, ever" introduce a consumption tax in Australia and took this policy to the polls. A 4.8% swing against the coalition reduced its majority to just 13 seats.

Howard went on to be Australia's second-longest-serving prime minister, staying in the job until 2006.

Slumps through history

Bob Hawke suffered a swing against his government in 1984, but lost only a handful of seats

Australians have a history of punishing governments when they seek a second term.

Bob Hawke developed a minor case of the slump in 1984, when his Labor government's majority was cut from 25 to 16, surprising analysts who thought the popular PM would be returned with an increased majority.

Another Labor leader, Julia Gillard, suffered a particularly acute bout of slump in 2010, when a 5.4% swing against her government wiped its majority from 18 seats to zero, forcing her to do a deal with independents to stay in power.

Multiple complex factors were at play in each case. Hawke was forced to delay promised policies due to a hole in the budget and Gillard was always on the back foot after she deposed first-term prime minister Kevin Rudd in a coup.

But the pattern is clear to see - Australians typically return governments for a second term with a greatly reduced majority.

Turnbull is likely to secure 76 seats to Labor's 69, enough for the coalition to rule on its own. In this sense he is already doing better than Gillard, who still lasted almost an entire term before her panicking party ended her leadership and reinstalled Rudd, the man she deposed.

There's no doubt that Turnbull faces a tough road of internal unrest, unruly senators, an emboldened opposition and an uncertain global outlook. But his circumstances are hardly unique in Australian politics.

- Published10 July 2016