Infamous Australian race riots mined for dark laughter

- Published

Down Under follows two groups of young men on the hunt for violence after a race riot in Australia

No-one is a hero in a new Australian film that asks tough questions about racism, violence and stupidity, writes Clarissa Sebag-Montefiore.

In Down Under, the new black comedy on the 2005 Cronulla riots, one white "bogan" hothead called Jason suggests erecting a 20ft (6m) "Leb-proof fence" to shut Lebanese immigrants out of what he sees as his beach and his hood.

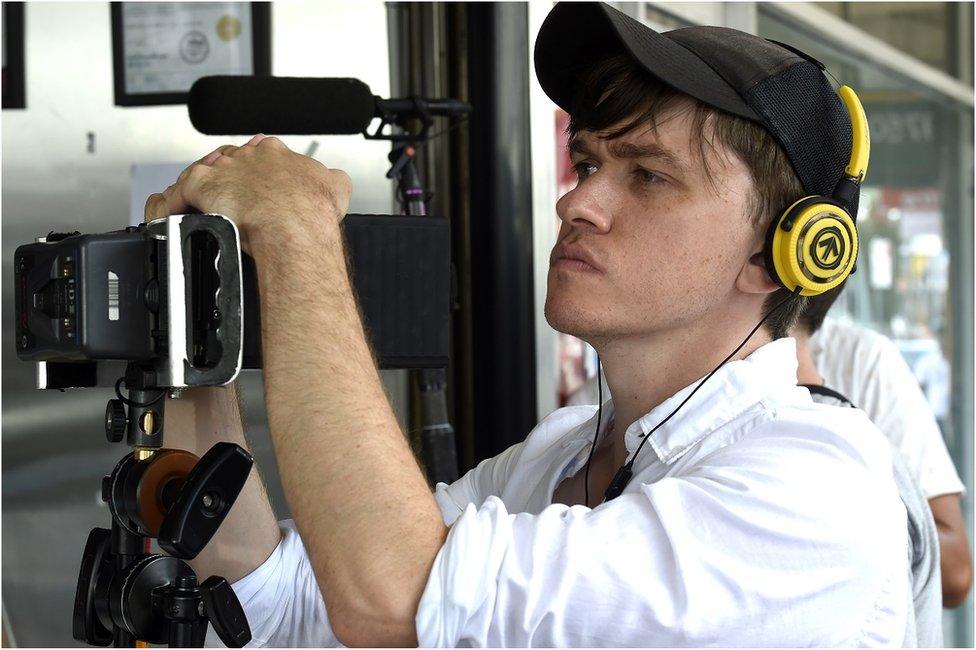

When Abe Forsythe penned the script five years ago, he could not have foreseen that American Republican nominee Donald Trump would suggest building something similar - this time a wall along the Mexican border.

In the film, the absurdity of the fence proposal is quickly pointed out by a bong-smoking video store employee,

"'The contracting would be a nightmare," he says. "And the federal government wouldn't give the go-ahead for something like that, it's got to be state specific… the local council wouldn't have anywhere near enough cash to build a wall that big."

His reasoning elicited spontaneous applause at the film's premiere in June.

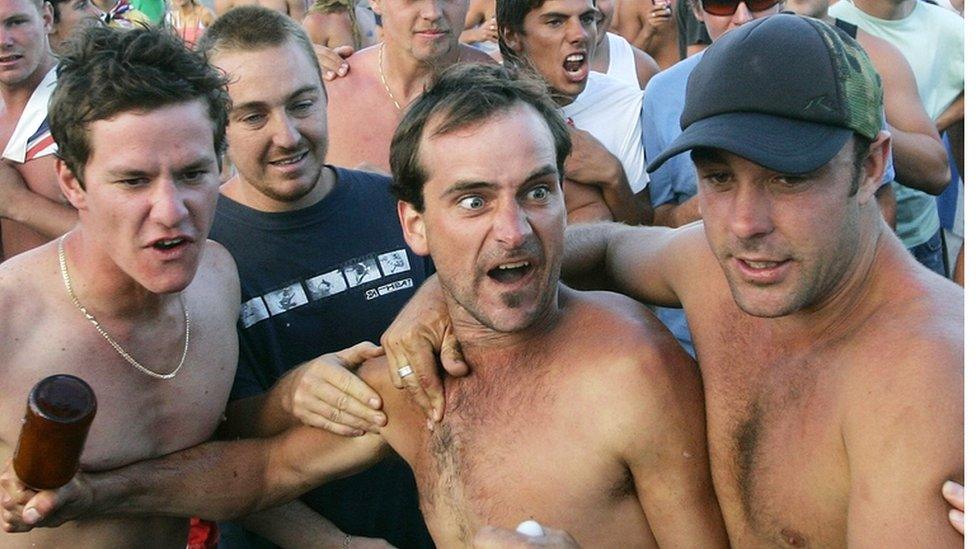

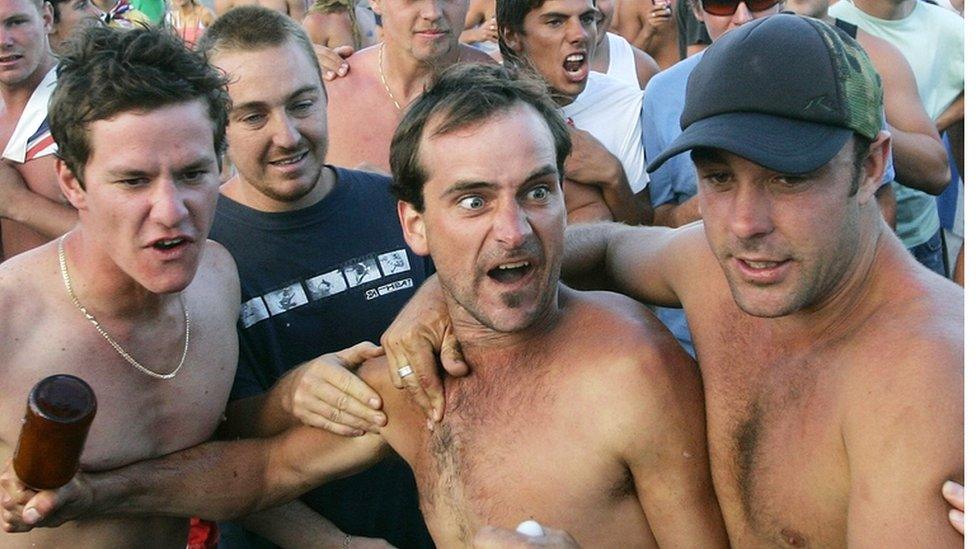

While a comedy, the film doesn't shy away from the brutal violence that the young men inflict upon each other

Down Under, released nationally in August, may be a quintessentially Australian movie based in Sydney on a day of race riots. But its themes of racism and xenophobia remain painfully present - and relevant worldwide - today.

Thirsty for revenge

"Casual racism is pretty much everywhere," says Sydney-based director Forsythe, 34. His aim is to "take something that we're living through and is ugly and difficult and attempt to shine a light on it with comedy".

Shot on a budget of less than A$3m ($2.3m, £1.7m), Down Under opens its story in the lead-up to Christmas 2005. As the soundtrack belts out We Wish You a Merry Christmas, real news footage shows intoxicated locals shouting about Lebanese immigrants as they play up to the cameras; in the background police wield batons.

What were the Cronulla race riots?

A week prior to the 2005 riot in the beachside Sydney suburb of Cronulla, two surf lifesavers were assaulted in what was said to be an unprovoked attack by a large group of men of "Middle Eastern appearance"

Texts and emails were used to circulate calls for a revenge fight and a crowd of about 5,000 gathered on the beach on 11 December

The crowd attacked two young men of Middle Eastern appearance and many then ran to the nearby train station after hearing that Lebanese passengers were arriving

There were retaliatory attacks from groups of young Muslim men

"The participants are inviting the camera into the event, that's what made it even more confronting," notes Forsythe. "To see all these boys and men full of adrenalin and peacocking for the camera. Taunting the camera, too."

The film concentrates on the retaliatory attacks that followed the riots. Two different gangs of men, one white, one Lebanese, both armed with guns and thirsty for revenge, race around in their cars looking for action. Jason, the rough leader of the Caucasians, tells his small daughter Destiny her Daddy's got to go and beat up some Lebanese migrants.

Set claustrophobically in the suburban sprawl that spans outwards from Cronulla beach, the movie gets its laughs from comparing the two opposing motley crews. Both attempt to be scary but are utterly ineffective. At one point, drumming this home, the whites, although desperate to be hard, can't help but do a car sing-along to The NeverEnding Story.

An actual image from the race riot that erupted in the seaside Sydney suburb of Cronulla on 11 December 2005

Meanwhile both groups - fuelled by testosterone, stupidity, fear and ignorance - are sent up as stereotypes that cut close to the bone. As their similarities, rather than differences, are exposed, neither comes away unscathed.

Raw emotion

But if Down Under starts as unapologetic satire - gags are fast and often cruel - it descends into brutal realist violence. The juxtaposition is deliberate.

First you "lull [the audience] into a false sense of security that it's a comedy," says Forsythe. Then you "pull the rug out from under them".

Forsythe, who wrote the first draft in three weeks, was living in London when the riots broke out. More than a decade later he believes that Australians still "haven't dealt with this stuff".

"When it happened everything was so raw. Then it kind of felt like the conversation stopped."

With the re-emergence of far-right parties across the globe, he thinks addressing the past is even more crucial.

"Certain groups on the fringes of society feel like they're under attack," he says.

"As a result they're forming packs so they feel safe. It all comes down to people feeling like they're not being heard."

Director Abe Forsythe wanted to keep politics out of the film and instead drill into the personal motivations of the characters

Forsythe is therefore careful to humanise his protagonists. The only major female character is Stacey (Harriet Dyer), Jason's girlfriend, who is heavily pregnant, foul-mouthed, and smokes.

As she sits on the sofa, wearing a crop top that showcases her enormous stomach and infected belly button ring, she eggs on her violent boyfriend. Yet the pair also share moments of real tenderness.

Hassim (Lincoln Younes), a studious, hard-working young man of Lebanese origin, reluctantly joins in the retaliation to find his missing brother. He is one of the more sympathetic characters, yet even his actions are foolish and rash.

By focusing on individuals, Forsythe keeps politics out of the film; he wanted to avoid being seen as a filmmaker "out to lecture". Humour was a tool to prevent that happening. And like all good comedy, the more painful truths get the best laughs.

Even so, "the movie has been a battle every step of the way", admits Forsythe.

"It is a piece of entertainment," he adds. "But one that condemns."

As for the wall, it won't be built in Cronulla. Whether it will in America remains to be seen.

Clarissa Sebag-Montefiore is an arts and culture writer based in Sydney

- Published7 December 2015