Sea snails could save Great Barrier Reef from starfish

- Published

Pacific triton sea snails are partial to eating the crown-of-thorns starfish despite its poisonous barbs

A giant sea snail could be the answer to getting rid of coral-eating starfish from the Great Barrier Reef, Myles Gough reports.

Australian researchers are investigating whether the scent of a natural predator can help repel millions of crown-of-thorns starfish (COTS) from corals on the Great Barrier Reef.

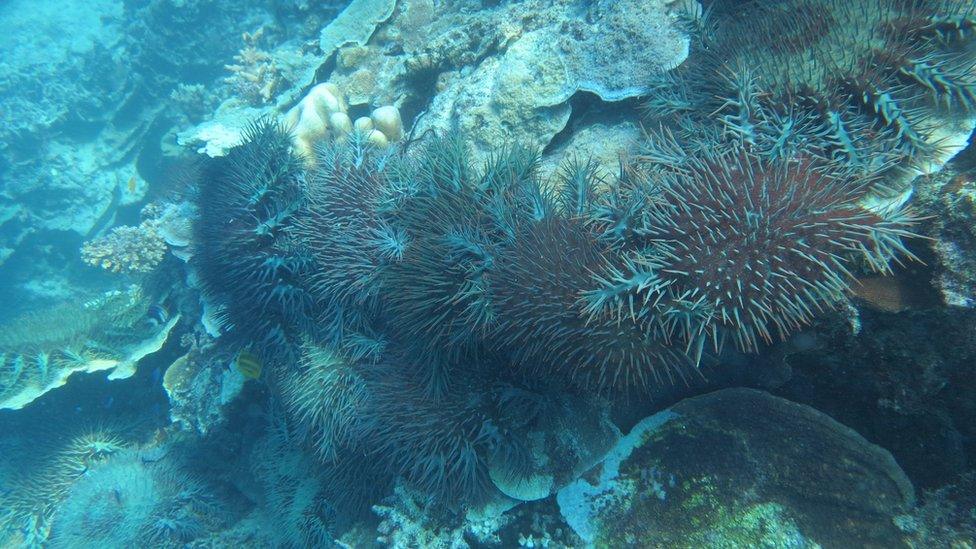

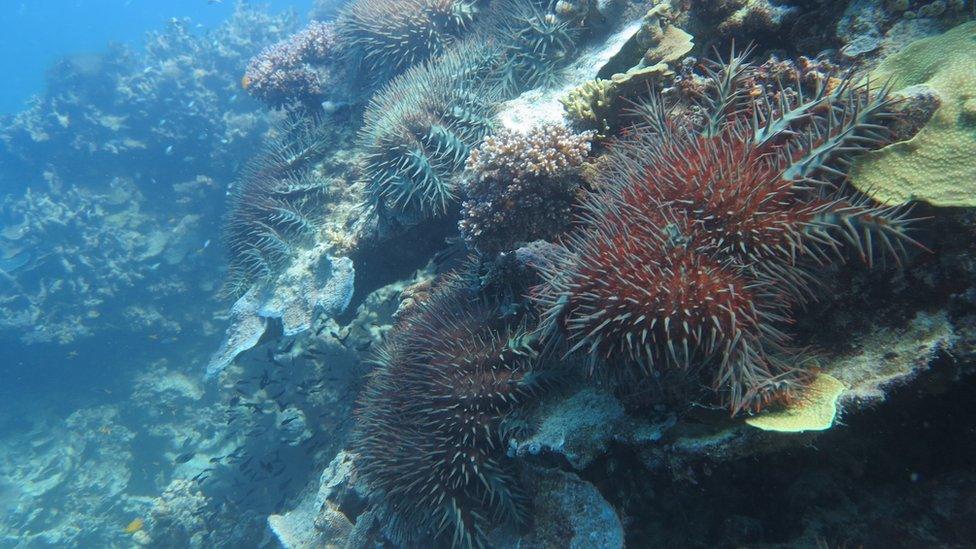

Crown-of-thorns starfish (Acanthaster planci) are native to reefs in the Indian and Pacific Oceans, but are one of the largest threats to corals outside of cyclones.

These animals, which are covered in hundreds of venomous spikes, feed on the flesh of corals until all that's left is a calcium carbonate skeleton. Between 1985 and 2012, they were responsible for 42% of all lost coral cover in Australia.

Crown-thorns starfish feed on corals until all that's left is a calcium carbonate skeleton

What makes the starfish so devastating is that they are prone to population explosions.

"It's a species a bit like locusts," says Dr Mike Hall, a marine biologist at the Australian Institute of Marine Science. "They're always around somewhere at low numbers, but every now and then there are large outbreaks."

An outbreak in 2015 resulted in an estimated 7 million COTS living and feeding on corals throughout the Great Barrier Reef. Just one animal can eat about 10sqm (110sq feet) of coral in a year, and this tissue never grows back, Dr Hall says.

At present, the best way to manage these outbreaks is by killing individual starfish one-by-one with lethal injections, which are administered by divers.

"On small local scales, this can protect reefs of high eco-tourism value," Dr Hall says. "But trying to do it on a whole Great Barrier Reef scale - it would be like a military campaign. You'd have to put a lot more soldiers out there on the reefs, injecting away."

Crown-of-thorns starfish on the Great Barrier Reef

It's simply too costly. But with more outbreaks likely in future, and corals under increasing stress from climate change and bleaching events, better management strategies are needed.

Snail rescue

Hall's outside-the-box solution is to use the Pacific triton (Charonia tritonis), a large sea snail known for its beautifully coloured shell.

The Pacific triton is one of the only natural predators of COTS. Native to the same habitats in the Indo-Pacific region, this giant snail, external is adept at devouring the starfish, toxic spikes included.

But Dr Hall's not interested in their appetite. Instead, he wants to harness the chemical scent these snails send out into the marine environment to manipulate the behaviour of COTS.

His team has already demonstrated that COTS can detect the presence of a triton: "They rapidly try to get out of the way and go into hiding to avoid being eaten," he says.

This video, external shows how the normally slow-moving COTS react to the fear-inducing chemical scent released by its natural predator.

"In a terrestrial environment, a farmer might use a scarecrow," Dr Hall says. "In the marine environment, the same thing works by smell."

He's hoping to trick the COTS into fleeing their coral settlements.

Halting future outbreaks

Researchers suggest crown-of-thorns starfish could be repelled by underwater scent

Pacific tritons could be farmed and released onto reefs like "Swat teams" to drive an exodus of COTS, Dr Hall says. As they are slow-moving and colourful, they could later be collected and re-deployed elsewhere.

This might avoid the collateral damage of leaving the snails there permanently to eat other organisms, such as sea cucumbers.

Dr Hall's ultimate goal, however, is to identify, isolate and synthesise the fear-inducing chemical compound that's released by the triton in order to develop slow-dissolving capsules. The scent would linger and create the illusion of tritons being present on the reef.

Although these solutions wouldn't kill the starfish, Hall believes they could disrupt their breeding habits enough to "potentially break the outbreak cycle".

"They would be in panicked, alarmed state rather than concentrating on being close to each other and spawning," he says.

His team is also trying to understand the chemical signals released by the COTS themselves, including one that apparently causes the animals to cluster together.

If this scent could be manufactured, Hall says it could be used to force them into one location, where they could more easily be culled or collected in a trap.

Desperate times, 'far-fetched' measures

Dr Jon Brodie, chief research scientist at the Centre for Tropical Water and Aquatic Ecosystems Research at James Cook University, says we need a new management strategy for controlling the coral-destroying starfish.

"Manually killing tens of thousands of crown-of-thorns starfish each year simply can't have an effect on an entire population of up to 10 million."

Dr Brodie says it's "highly unlikely" that the chemical scent of tritons will be an effective deterrent for COTS but he says all options should be considered:

"I think it's a far-fetched solution, but times are desperate for the Great Barrier Reef," he says. "It's in terrible shape."

"I'm not against spending more money to investigate the option because it might just work."

Dr Brodie says there also needs to be more focus on managing water quality, including nutrient runoff from farms, which is believed to cause COTS outbreaks.

- Attribution

- Published2 March 2016

- Published29 May 2015

- Published28 October 2014