The Australian town that wants to get off the grid

- Published

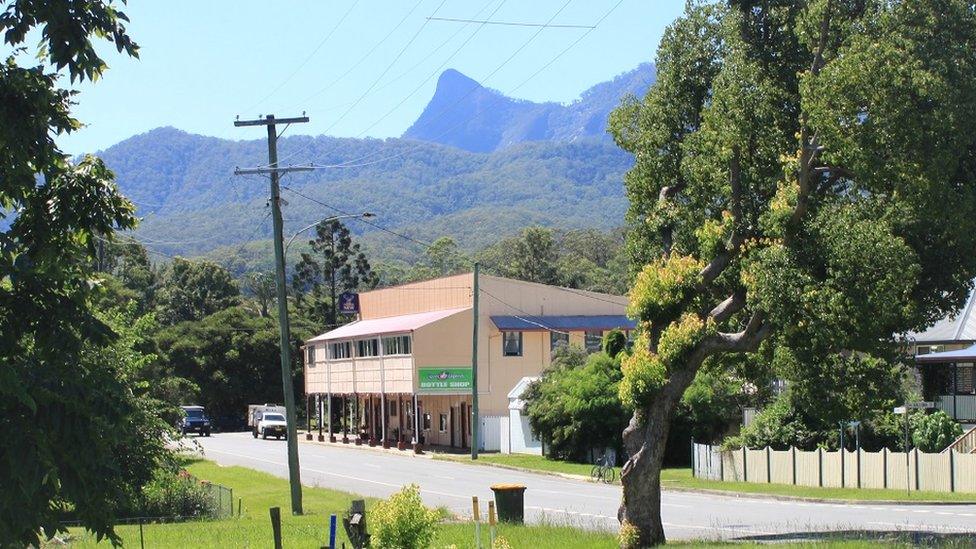

The town of Tyalgum has just 300 residents and is aiming to be taken off the electricty grid

It's hard to locate on a map, but a new plan to disconnect from Australia's power grid is bringing a surge of attention to the village of Tyalgum, writes Royce Kurmelovs.

The 300 residents of Tyalgum, set among the rolling hills near the Queensland-New South Wales border, are fond of saying their town is "beautiful 24-7".

Soon, if all goes to plan, this little town in a region famed for its alternative lifestyle could be the first place in Australia to get off the electricity grid and keep the lights on 24-7 using 100% renewable energy.

The idea was hatched in September 2014 by local entrepreneur Andrew Price, a 10-year veteran of the renewable energy industry who runs the company Australian Radio Towers.

"Why off the grid? Why not?" Mr Price tells the BBC.

"The power is cheap, it is reliable and currently solar is about as green or renewable as anything else on the market today. Taking an entire town off the grid also makes a statement to the country that this can be done and that it should be done."

While Tyalgum may be an unlikely place to wind up at the forefront of a renewable energy revolution, there are several reasons why it is well suited to the project, the plan's proponents say.

Solar energy systems will be distributed to owners of major buildings using a lottery system

Firstly, sustainability issues are close to the town's heart, Tyalgum has been locked in an ongoing battle to stop fracking in the region and community support for environmentally friendly projects runs deep.

The town also happens to lie at the very end of the electricity grid, meaning it can be disconnected without disrupting energy supply to neighbouring communities.

Then there's Tyalgum's economic makeup - the town is reliant on tourism and there are few stable jobs, so electricity bills hit locals hard.

According to Mr Price, the 300 people of Tyalgum collectively spend A$700,000 (£406,000, $534,000) a year on electricity, with 55% of that going to maintain the poles and wires.

'A social licence'

The project to take the town off the grid has attracted A$15,000 in government funding so far.

Kacey Clifford, who helps lead the project, says maintaining and deepening community support over the long term will be vital in making the project viable.

"It was important to get the community to back the concept before we developed the solution," Ms Clifford says. "I think they refer to it as getting a social licence.

"It just seemed like the right way to do it, rather than just turning up with authority and providing the solution."

Installation of the solar systems, complete with panels and battery storage, is expected to begin in October.

The team at the Tyalgum Energy Project says broad community support is essential to its success

Solar energy systems will be granted to property owners across the town through a lottery. They will then pay a portion of the money they save on electricity into a fund which will be used to install systems on the other 120-odd homes in town.

Building the infrastructure needed to take the entire village off the grid is expected to cost A$7m.

A feasible endeavour?

The town also needs permission to cut the cord - there are regulations that govern the way power is generated, distributed and sold in the existing power grid.

Tosh Szatow is director of energy management firm Energy for the People and wrote the feasibility study for the Tyalgum Energy Project. He says meeting regulatory requirements is "easier than what people think".

"The regulators have been held up as a problem with big projects like these, but really it is coming up with a sensible plan that keeps the regulator happy," he says.

"All the regulator cares about is the price of energy the customer is getting and things like security and reliability."

Independent energy consultant Craig Froome agrees that issues such as regulation, battery storage and negotiating ownership of the connecting wires are not problematic enough to sink the project.

The town is located in an area of northern New South Wales that's known for its environmentally conscious communities

"People are hesitant in doing anything until they see it working somewhere else. You need someone to take the initiative and do it," he says.

"In all honesty, it would be good to have a demonstration site that actually proves decentralised distribution will actually work. Can you actually take areas off the grid?"

But even if the project stops before reaching off-grid status, it won't be a total loss, Ms Clifford says.

"We don't see a risk at any point if we were to stop because people still have solar on their roof," she says.

"Our strategy is that we're going to put as much solar on roofs as we can, as many batteries that we can, have that infrastructure sitting there and then go to Australia and say we have all this stuff in play, what are you going to do about it?"

"It's guerrilla warfare in the renewable energy industry."