Australia's child poverty 'national shame'

- Published

Indigenous children are more likely to live in poverty than their non-Aboriginal counterparts

It is one of the wealthiest countries on Earth - enriched by the bounty of a once-in-a lifetime mining boom - but Australia remains bedevilled by a rising number of its children living in poverty.

Trapped by disadvantage are more than 730,000 youngsters, according to the Australian Council of Social Service (ACOSS), external.

It laments a "national shame", and its research suggests about 13% of the population - or three million people - are living below the breadline.

Indigenous children suffer more than their non-Aboriginal counterparts. Single-parent families also endure great hardship.

Raising her two young children on her own, Jessica Russell, 25, relies on weekly welfare payments of A$545 (£338), much of which is swallowed up by renting a modest house in the Sydney suburbs.

"It is a really big struggle. I'm the biggest stress-head possible because I worry for my children," she tells BBC News.

"I don't want them to fall behind and not get what they deserve or need in life.

"I break down most nights because I can't give them everything that they need or want. I put myself last."

Jessica Russell would like to train to be a midwife

Ms Russell lives well below the official poverty line, which is defined as half of Australia's median income (about A$80,000).

At times, she says the pressure is overwhelming.

"It comes crashing down," she says as Ryan, three, roars past with a toy chainsaw, pursued by his brother, Andrew, one.

"They'll go to bed, I'll sit down and I will just be like, 'What have I done wrong? What have I done wrong to struggle so much?'"

It is almost 30 years since the then Australian Prime Minister, Bob Hawke, said: "No child will be living in poverty by 1990."

His bold promise would not be kept, but it did lead to significant progress in tackling inequality in the 1980s and 1990s, yet still the problem persists.

In the Ashfield district of Sydney, it is late morning and a crowd waits quietly outside the heavy wooden doors of the Loaves and Fishes Restaurant, a restored hall in the grounds of the 19th Century Uniting church.

Run by the Exodus Foundation, it serves 500,000 free meals to the needy each year.

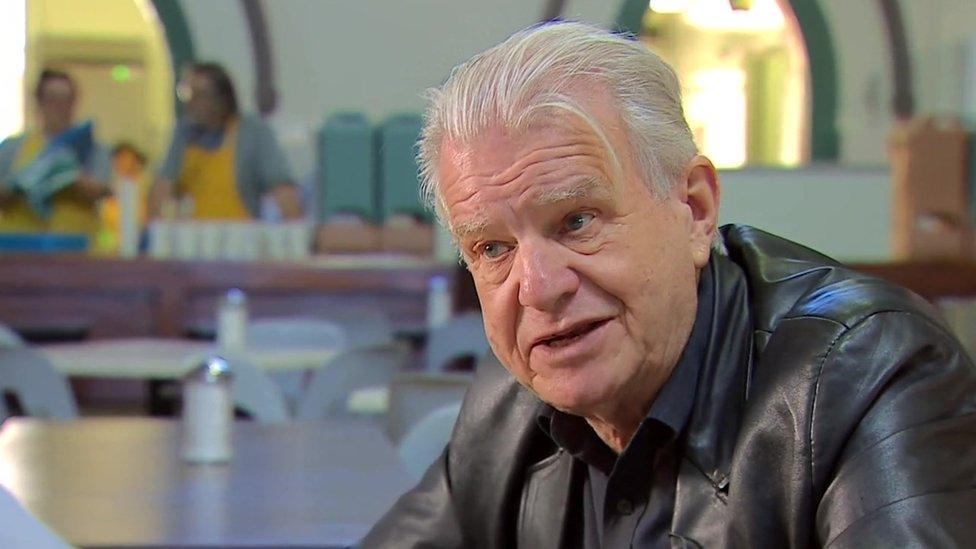

The charity was co-founded 30 years ago by the Reverend Bill Crews, the son of middle-class British migrants.

The Rev Bill Crews's Sydney charity provides 500,000 free meals each year

"We're forever struggling to keep up," he says.

"We'll come across a family who have been living on pancakes for a week because there hasn't been enough money.

"This is a country that could lead the world in a good way to live.

"It has got the will in its people to be egalitarian and show the way.

"One hundred years ago, Australia showed the way.

"It is very sad to me to go to countries overseas where you expect to see poverty, and then come back here and see the same poverty here."

The ACOSS report indicates one in six children in Australia is living in poverty, a 2% increase during the past decade, when the nation's coffers brimmed from a multi-billion dollar bonanza forged on exports of iron ore and other prized resources.

Charities blame the soaring cost of living and a lack of affordable housing for stubbornly high levels of poverty.

They fear the government will start curbing welfare payments.

The federal government has said the best way to tackle poverty is to create more jobs.

"People see Australia as the place where you can come and get your own house, bring up your family and you won't have any problems, but we are seeing an increasing population of those people that are finding it tough," says Ben Carblis, from Mission Australia, a non-denominational Christian community service organisation.

"It is hard to believe."

This grim assessment of life for millions of hard-pressed Australians is not, however, universally accepted.

David Leyonhjelm, a Liberal Democratic senator in Canberra, has questioned how levels of disadvantage are calculated and believes the scale of the problem has been overblown.

"Poverty does exist in Australia, if you are talking about not having enough food, nowhere to live and no clothes to wear, but it is nowhere near 13% - nowhere near that," he tells BBC News.

"The people who work for those charities have their careers tied up in the continuation of that charitable work.

"If they were too successful and poverty was eliminated, they wouldn't have jobs anymore.

"They have a very long history in Australia of talking up poverty."

The federal government has said the best way to tackle poverty is to create more jobs.

Ms Russell wants to train to be a midwife when her boys are older, but for now can see no end in sight to the daily grind of life below the breadline.

"I have two gorgeous, gorgeous children, and I still feel like there is something more that I can do, but I can't pinpoint what it is, and it breaks me because I don't know how to fix it," she says.

- Published31 August 2016

- Published9 June 2016

- Published21 February 2016

- Published31 October 2014