'Vanpacker' tourists irk councils on Australia's coast

- Published

French tourists Anthony Fenech and Pierre Stoar are travelling around Australia in their van

Its official name is Tamarama but it's known as Glamarama for the beautiful people who sunbake on the golden strip of sand wedged between two striking headlands in Sydney's pricy eastern suburbs.

There are no hotels in Tamarama, though a night in a multi-million-dollar home overlooking the strip with letting agency Luxe Houses starts at A$2,500 (£1,478; $1,848).

But Anthony Fenech and Pierre Stoar, two backpackers from France travelling around Australia on a surfing safari, have found a cheaper option.

They pay nothing to sleep in the back of a beat-up old van they bought in Melbourne and park on Pacific Avenue, Tamarama's premier address. They use the beach toilets and showers, they cook their meals on public barbecues and dry their laundry on a handrail overlooking the beach.

"It's great for us, we have the same view as the people living up there," Fenech says. "This is a beautiful country, a great country where I can sleep anywhere for free."

No parking

What Fenech and tens of thousands of other so-called "vanpackers" on the annual migration up Australia's east coast fail to understand is that these things are not free. The cost of the amenities and cleaning up the mess vanpackers invariably leave behind is borne by ratepayers who then have to put up with rusty old vans clogging up parking spaces in their neighbourhoods and blocking exclusive views.

"It's a real problem because they cook on the side of the road and pour oil into stormwater drains that go into the sea, which we find quite offensive, and because they don't have toilets in their vans, they do things one should not do in parks," says Sally Betts, mayor of Waverley Council, which has jurisdiction over Tamarama Beach.

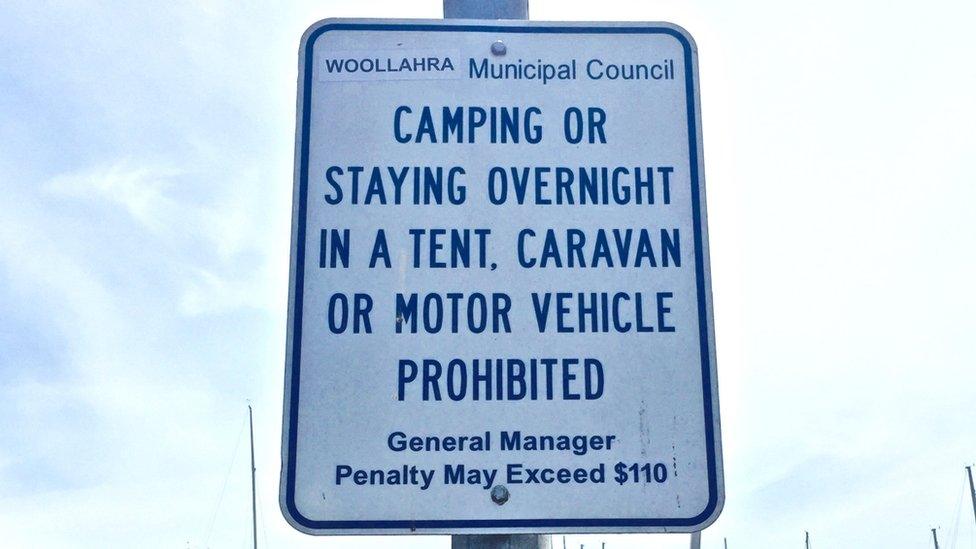

Councils complain they can do little more than issue fines

"It's very complicated from a legal point of view," she explains. "We wanted to put up a big sign that says no camping or sleeping cars in all of Waverley but legally we couldn't even do that. All we can do is put up signs on individual streets, and then we have to send our parking rangers down to fine them."

Some 450km (280 miles) north of Sydney is Crescent Head Foreshore Reserve, a manicured parkland edged by one of the most famous surfing beaches in all of Australia. Crescent Head attracts surfers from all around the world, a growing number of whom took to sleeping in vans parked off the beach. Last Christmas, reports of anti-social behaviour became so prevalent that Kempsey Shire Council held an emergency meeting to resolve the problem that was attended by more than 100 residents.

Their riposte? Parking restrictions, rangers and fines in a quiet and beautiful part of the world that previously had no need for such measures. But director of infrastructure services Robert Scott said the council had no choice: "We have listened to what the Crescent Head community have told us and believe this is the best solution to increase turnover of parking spaces."

A gap in the market?

But are fines an effective deterrence? The evidence suggests not.

Another 350km north of Crescent Head is Byron Bay, a beachside town of 5,000 that receives a whopping 1.7 million visitors each year. With silky waves, free live music and an alternative lifestyle, Byron is also ground zero for vanpackers.

In 2011, Byron Shire Council introduced no-parking zones between 01:00 and 05:00 and fines of up to A$500. But vanpacking persists in Byron Bay. In the first 10 months of this year, the council issued 1,400 fines and 160 warnings. "It's literally a moving problem," says sustainable development manager, Wayne Bertram. "When it is resolved in one place, it pops up someplace another."

Byron Bay is a popular destination for vanpackers

Theo Whitmont, president of the Caravan & Camping Industry Association (CCIA) of New South Wales, says vanpacking shows there is an unmet need for affordable accommodation in Australia. "The tourism industry should come together to offer them an array of places to stay," he says. "All we have to do is identify land in transit corridors near coastal areas for no-frills camping."

Mayor Betts says Waverley Council could not possibly afford to buy land to accommodate vanpackers. But Richard Barwick, CEO of the Campervan & Motorhome Club of Australia (CMCA), says such options already exist. "There are 1,500 caravan parks in Australia and we have also worked with councils to create 290 RV-friendly towns where they provide free parking for RVs."

Yet as Barwick points out: "Our members' vehicles are self-contained with kitchens and bathrooms. But these backpackers in small vans, they rely on infrastructure that has been set up for day visitors. And when our members visit those beaches, they get fined even though they're not the ones making problems. So it's a difficult problem and councils need to take a proactive approach rather than an aggressive one."

A gentle word can do wonders

A pretty little beach on the bay with barbecue facilities, pergolas and drop-dead gorgeous views only 6km from Melbourne's CBD, Sandridge Beach was once overrun with vanpackers.

"There are about 20 car spaces and we had backpackers living there for up to three months a year," says the mayor of the City of Port Phillip, Bernadene Voss. "It was never clean, the volunteers at the lifesaving club couldn't park their vehicles and the neighbours complained. This went on for about two years."

But complaints from residents have dropped by two-thirds this year and Sandridge Beach is now vanpacker-free. The solution, says Voss, lay in a personable approach.

Fewer vans line Melbourne's Sandridge Beach after a change in council approach

"We had patrols go down where these international backpackers park their vans and knock on their windows at 5am," she says. "Now, no one wants to get woken up at that time, but these international backpackers would have a chat with our rangers all the same and receive information on where they can legally camp. We do not typically fine them. There's no point anyway because they can leave the country without paying the fines. Apart from one or two cases, they have been very responsive."

But won't a new wave of vanpackers just replace them next year?

No, says Voss, because vanpackers are sharing news on the social media that Sandridge Beach is closed for business, and police now patrol the area at night.

"Honestly I don't think this is that hard of a problem to solve," says Whitmont of the CCIA. "All we need is for everyone to be reasonable. But people who want to camp for free in streets with million-dollar views are not being reasonable."