Could ex-child soldier Deng Adut be Australian of the year?

- Published

On Australia Day, in late January, the nation will celebrate the achievements of the selfless, the brave and the inspired.

The nominees for the coveted Australian of the Year award, external include a scientist treating spinal cord injuries, a retired rugby league player and a billionaire mining tycoon.

Also in the running for Australia's most prestigious civic honour is a former Sudanese child soldier, who arrived in Australia a 14-year-old illiterate refugee.

Named after the god of rain, Deng Adut is now a successful criminal lawyer in Sydney and the 2017 New South Wales (NSW) Australian of the Year for his work with African migrants.

"Deng represents the very best of what makes our country great, and has channelled his success into helping hundreds of people in the state's Sudanese community navigate their way through the Australian legal system," said the NSW Premier Mike Baird.

Deng's story is full of Hollywood drama - kidnapped as a child, forced into military service, shot in the back and later smuggled to freedom hidden in a corn sack on the back of a lorry.

He was born in Malek, a small fishing village. His father was a fisherman and the family lived on a banana farm.

"When I was first conscripted, I was six," he recalled.

"My first tour of duty was when I finished my military training at nine.

"I had my first AK47 when I was nine, and it was a beautiful piece of equipment at the time for a child. It was just like a toy."

"I was a child soldier, and I was expected to kill or be killed."

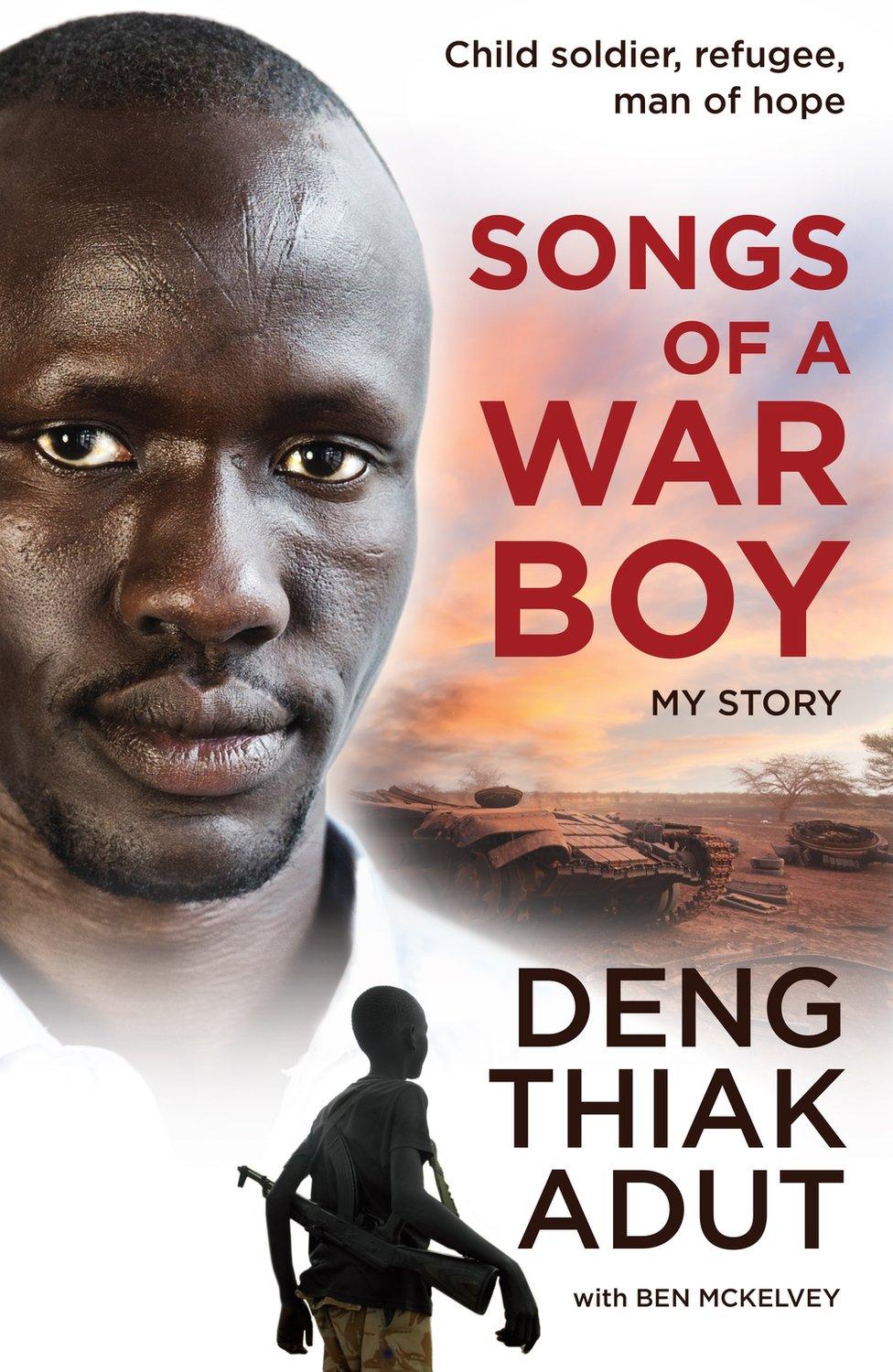

Deng's remarkable life is detailed in a recently published biography, Songs of A War Boy, which he co-wrote with author and close friend Ben McKelvey.

"He was taken from his village when he was six, then marched to Ethiopia and was press-ganged into the SPLA, the Sudanese People's Liberation Army, which is the group that is in power in South Sudan at the moment," McKelvey told Australian radio.

"[He] fought in a couple of horrific battles, was an internally displaced person for a while then came to Australia, taught himself English, did a law degree and now is the man you see today."

Deng was eventually spirited out of Sudan and taken across the border into Kenya, hidden in the back of a truck.

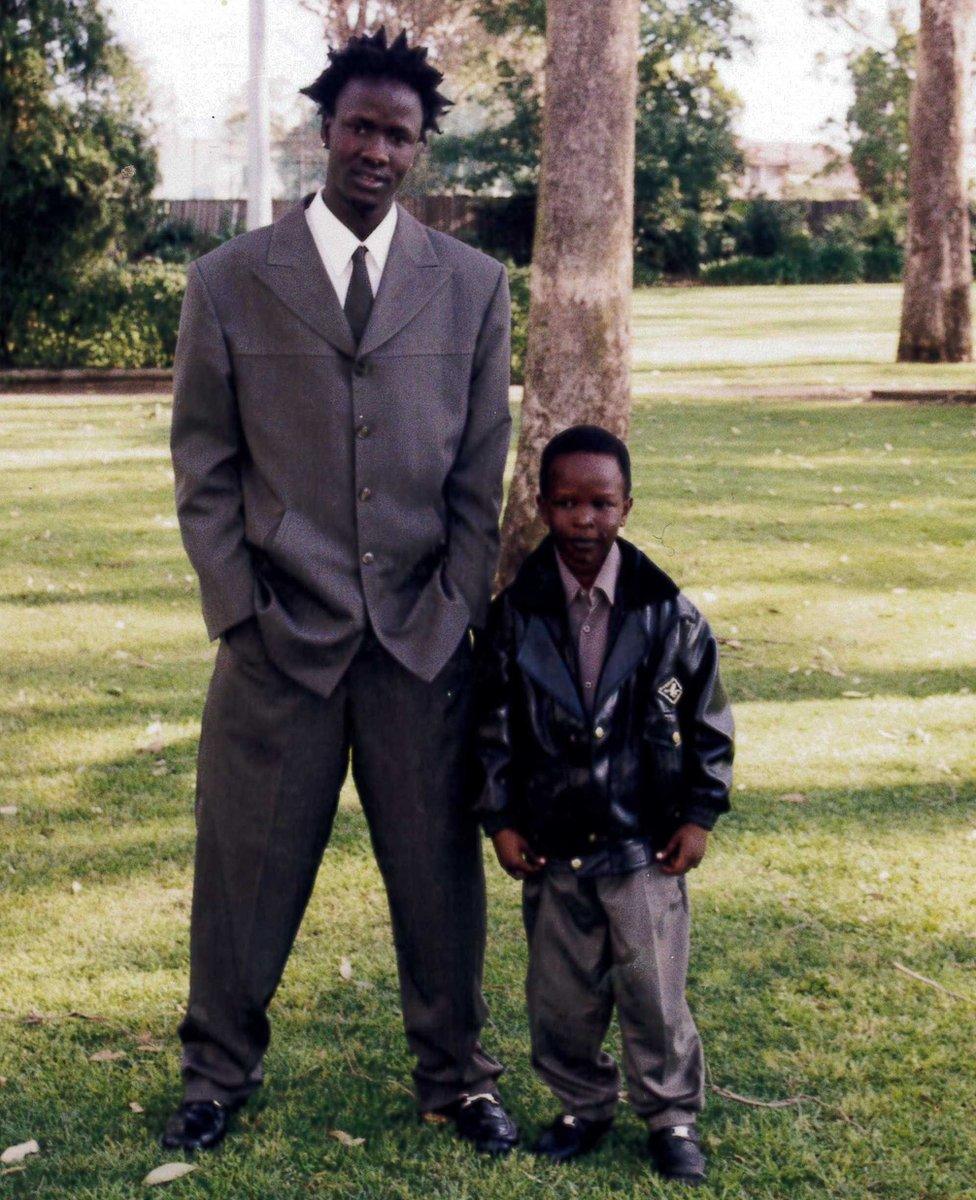

Helped by his half-brother John, he befriended an Australian couple and the boys arrived in Sydney as refugees in 1998.

Odd jobs making concrete, fitting doors and windows and shifts in a meat factory would serve as an apprenticeship for what was to come.

They forged a determination that would see a former child warrior complete an advanced diploma in accounting before graduating with a law degree from Western Sydney University.

Deng Adut with his nephew Josh - he says Australia gave them both a fresh start

A video of his life produced by the university, entitled Deng Thiak Adut Unlimited, external, brought him widespread attention.

"I came to Australia as an illiterate, penniless teenager, traumatised physically and emotionally by war," he said in a speech earlier this year.

"My gratitude is to fellow Australians for opening the door, not only to me but to all the other migrants like me. Without your spirit of a fair go, my story could not have been told."

Australia has pledged to increase its annual intake of refugees from 13,750 to about 19,000, but the debate over immigration is often toxic and divisive.

Immigration Minister Peter Dutton has suggested it was a mistake to resettle many Lebanese Muslims in Australia, insisting that many suspects charged with terror-related offences came from that group.

Pauline Hanson making her maiden speech: Australia is in danger of "being swamped by Muslims"

In September, the anti-immigration One Nation senator Pauline Hanson used her maiden speech in parliament to say Australia was "in danger of being swamped by Muslims who bear a culture and ideology that is incompatible with our own".

Later this month, Deng Adut will be honoured at a function at the NSW parliament hosted by the independent MP Alex Greenwich.

He believes the awarding of the 2017 New South Wales Australian of the Year to the refugee from Africa is something the nation should be proud of.

"It shows that we are a country that does welcome people from adversity," Mr Greenwich said.

"It shows that the Australian character is one of warmth.

"Sadly, we can often be misrepresented by some of the policies of our federal government and the tone of some of the more extreme elements of our federal parliament."

Deng Adut has campaigned for Australians to show more tolerance to refugees

Deng Adut agrees that some migrants can be unfairly demonised in Australia.

"We look at them as people that are either invaders, we look at them as people that are coming here to cause problems, we look at them as people that are generally not suitable for this society," he said.

Deng has emphatically disavowed these perceptions of refugees and asylum seekers. For him, the chaos of the past has been replaced by an inner peace.

"I liberate myself from a lot of things," he said.

"I liberate myself from war, from poverty, so I liberate myself from those aspects of life that I know I have been through. Even death - I liberate myself from death."

- Published15 September 2016

- Published18 August 2016

- Published17 August 2016

- Published11 August 2016

- Published31 October 2017