The big row over a small Australian statue

- Published

A statue honouring so-called "comfort women" outside a church in Sydney

Outside a church in suburban Sydney sits a bronze sculpture of a young Korean girl in traditional dress.

She stares in silent protest, a symbol of the estimated 200,000 women were forced to work for the prostitution corps of the Japanese army during World War Two.

But the 1.5m (5ft) statue is suddenly drawing international anger.

Last week, a Japanese lobby group lodged a racial discrimination complaint with the Human Rights Commission in a bid to remove the statue from Ashfield Uniting Church in Sydney's inner west.

You might also like:

The complaint states: "This hurtful historical symbol is detrimental to the local community and will only result in generating offence and racial hate."

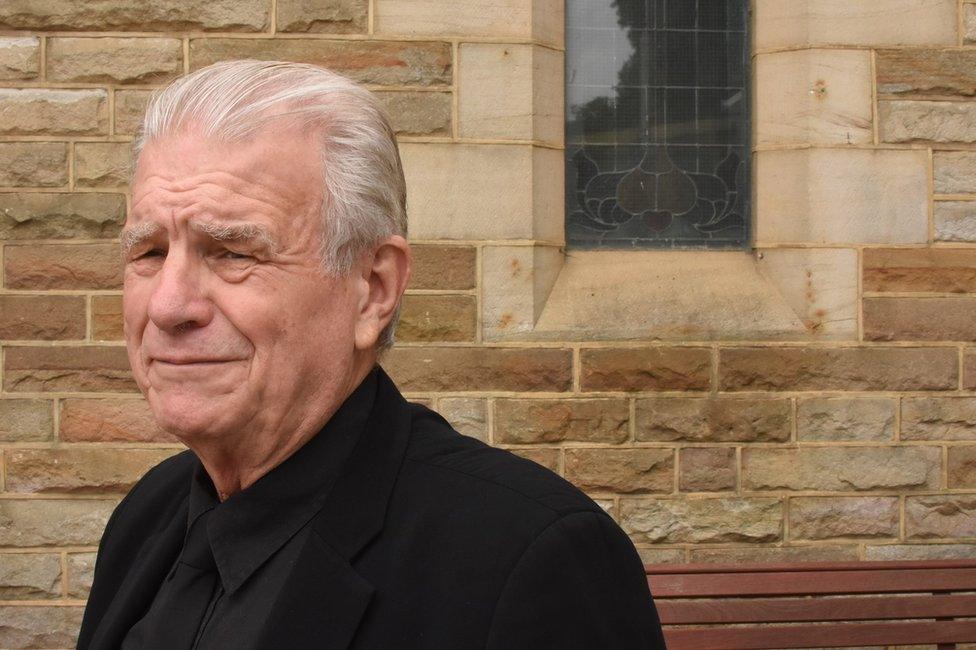

But the Reverend Bill Crews, who agreed to host the statue this year, says he will not be intimidated by legal threats.

"I just say bring it on," he says. "It's about the way women get treated in war. It's not anti-Japanese."

Bill Crews agreed to place the statue at his church

Tensions between Japan and South Korea over the so-called comfort women reignited in 2011 when activists installed an identical statue opposite the Japanese embassy in Seoul.

Memorials have since been placed in 40 cities in South Korea, seven in the United States and one in Canada. This is the first erected in Australia.

The Japanese government has repeatedly apologised and offered compensation for its painful legacy.

Parents 'worried'

The group opposed to the statue, the Australia-Japan Community Network (AJCN), does not dispute historical facts. But it argues the memorial inflames racial tensions.

"We are taking action only because the statue is designed to be a symbol of anti-Japan demonstrations," said the network's president, Tetsuhide Yamaoka, in a statement from Tokyo.

"We are a totally independent local group of mothers and fathers worried about the welfare of their children in Australia."

Mr Yamaoka claimed similar statues had spurred bullying in the United States, giving examples of Japanese children being spat at or told they were an "evil race".

Australia-Japan Community Network president Tetsuhide Yamaoka

The Korean community group behind the statue, the Peace Statue Establishing Committee, denies having an anti-Japan agenda.

"I don't think the Japanese are willing to accept what they've done in the past," said Vivian Pak, the committee's president.

"All we want is to let the world know the truth and that these crimes, these atrocities, should never be repeated."

The statue was originally meant for a park in nearby Strathfield, but the council rejected it following a petition that gained more than 16,000 signatures.

Racial discrimination claim

The AJCN is pursuing its claim through a controversial section of Australia's Racial Discrimination Act.

The law outlaws behaviour likely to "offend, insult, humiliate or intimidate" people on the basis of race, colour or ethnic origin.

But Prof Simon Rice, from the Australian National University, says only a "tiny percentage" of such cases make it to court.

"The law has been there for 20 years," he says. "Even if there is a spike in complaints, if those complaints are vexatious or frivolous, they are just not going to get anywhere."

Meanwhile, Mr Crews says lawyers have offered to defend the case pro-bono.

He also said the statue would not be moved.

"It's finally found a home."