A question fit for a car park: who can call Australia home?

- Published

The show takes place in a car park in western Sydney

A car park in ethnically diverse western Sydney is the scene for a thought-provoking show about Australia's identity, reports Clarissa Sebag-Montefiore.

An Aboriginal elder sets fire to a cluster of native leaves, letting pungent smoke curl into the sweltering summer sky.

This traditional smoking ceremony is not taking place in the bush, however. Rather, he stands next to a steady stream of traffic in Blacktown in western Sydney.

The ceremony marks the start of Home Country, a play that takes place entirely in a multi-level car park, with storytelling juxtaposed against manmade concrete.

According to the 2011 Australian census, 32% of people in greater Blacktown are from countries where English is not their first language. Set in an urban centre with more than 180 different nationalities, the performance asks: who can call Australia home?

"It's a conversation that we think we should be having as a country. And we're really well placed in western Sydney to have that conversation," says director Rosie Dennis of the Sydney Festival world premiere, a joint Urban Theatre Project (UTP) and Blacktown Arts Centre production.

Shunning an elite setting

Located around 35km (28 miles) from Sydney's central business district, Blacktown has more than double the New South Wales state average for murders and triple the number of robberies.

Yet Home Country wants to reach out to the local population by slashing prices for residents, who pay just A$20 (£12; $15) instead of the usual A$59 ticket price. It also seeks to take theatre out of elite buildings into everyday spaces - in this case, the car park.

Musicians Kween G, Mohammed Lelo and James Tawadros

Actors Danny Elacci and Nancy Dennis in the show, which happens as the sun sets

"We're looking at multiple perspectives and waves of migration, as well as traditional custodians of the land," says Dennis. "Each work is stand-alone. It's not a single vision, it's a multiple vision that adds to the layer of complexity of the conversation."

Those visions - performed by actors ranging from Aboriginal to African - include two neighbours making small talk on a balcony that ends in a heated discussion of race, and a second-generation Greek man who questions what home might be like without his sick mother.

With the audience guided through different spaces, it aims to provide a more nuanced portrait of both Blacktown itself and the different immigrants who make up Australia.

"If you're not first nations people, you've come here from somewhere else. We're all visitors," points out Ugandan-Australian hip-hop artist Kween G, who acts as MC for Home Country, and moved to Australia as a child seeking asylum with her family.

Just add food

Central is a communal feast included in the ticket. On a hot Friday night, as the sun went down over the Blue Mountains, Ethiopian food was dished out to the sounds of the kanun, a string instrument common in the Middle East, West Africa and Central Asia.

Food is intimately connected to identity and a route into another culture. It's also a conversation starter, says Julieanne Campbell, general manager of UTP: "When you have a shared meal, conversation and connection with people is part of the eating experience."

The audience enjoys an Ethiopian banquet after the show

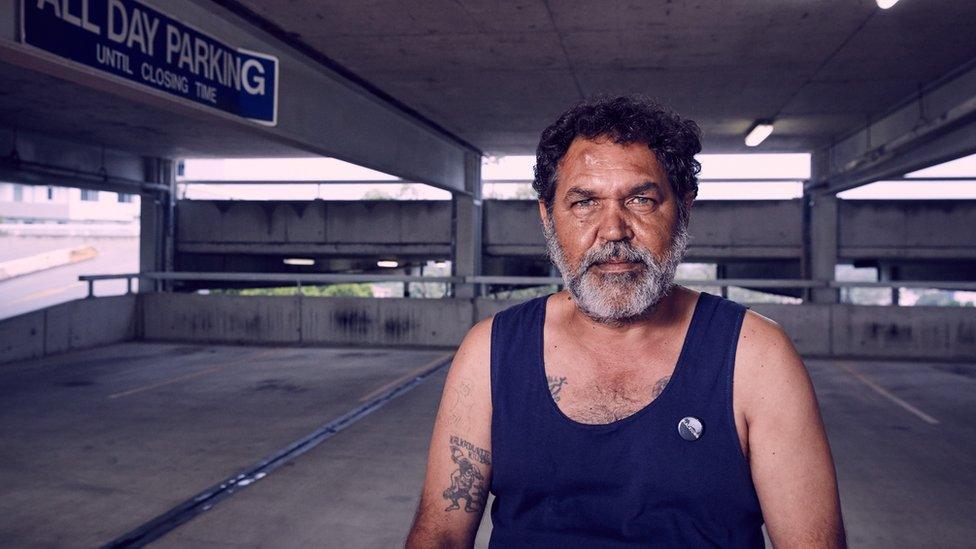

Billy McPherson as Uncle Cheeky

Nutritionist and audience member Linda Mitar, 39, agrees. Tearing into injera, an East African flatbread, she looks around the feast for 200 people, where guests range from small children to those in their sixties.

"I've spoken to every other person at the table which I normally wouldn't do - it's communal and goes with the theme of being welcomed," says Mitar, who was attracted to Home Country's juxtaposition of "ancient wisdom and sacred ritual in the centre of a busy city".

The event has made her rethink her views on Blacktown, too: "It did have the worst reputation. But given installations like this, it's made me realise how I've under-utilised and haven't appreciated what it can offer."

For local Robert Harcourt, 50, also attending, Blacktown is often "a place people have forgotten about". But he says that's changing because "there's growing pride".

"The past has been designed around the needs of cars," he adds. "To see for one night the cars cleaned out of here and thus space handed over to the public as a place of theatre, of music, of food, of community, that's the strongest thing for me."

'Relevant to people's lives'

For creators, it was crucial to turn spectators into participants and knock down the so-called fourth wall in theatre.

The setting is "outdoors, its connected to a local area, it's in a high point in the city, so you get a vista," says Campbell. "It's a sense of the everyday as well. When you're doing a work that's set in western Sydney, a car park is somewhat relevant to people's lives."

Home Country is showing as part of the Sydney Festival

Most important, Home Country acts as a source of inspiration. Aboriginal actor Billy McPhersan, who plays Uncle Cheeky, a chirpy, if emotionally lost, elder, believes that the play shows what's possible.

"Nothing like this happens out here," he says. "But I reckon [Blacktown] is going to be on fire."