Refugee's medical emergency reignites debate in Australia

- Published

Australia detains asylum seekers on the small Pacific nation of Nauru

As the US-Australia refugee deal dominated headlines this week, a medical emergency was unfolding at an Australian detention centre on the Pacific island of Nauru.

Advocacy groups have been pushing the Australian government to allow a Kuwaiti refugee, who is 37 weeks pregnant, to be flown to Brisbane to give birth by caesarean section.

They say they alerted the government that she was a high-risk patient in December, due to the condition of pre-eclampsia, her baby being in the breech position, because of her age of 37 and because she had been prescribed the antidepressant citalopram, which can result in harmful side-effects on newborn babies.

Known only as "Dee", the woman has been on Nauru since late 2013 and is now living in the local community after being deemed a genuine refugee.

However, with Australia having not approved her entry, the woman had remained in Nauru's general hospital. While previously refugees on Nauru were routinely allowed into Australia to give birth in better-equipped hospitals, Australia has been reluctant to allow the practice since 2015, fearing that once in the country refugees will seek legal help to remain here.

Finally on Friday, Dee was flown to Brisbane. According to Nauru's government, external, it came after Australia gave permission late on Thursday night.

Conditions for refugees in Nauru have been criticised by rights groups

Australia sends all asylum seekers who arrive by boat to detention centres in Nauru and Papua New Guinea's Manus Island. Those processed there and classed as genuine refugees have been released into the local communities. Children of asylum seekers who give birth in Australia are not automatically given visas or citizenship.

This "Pacific Solution" has been criticised by refugee advocacy groups, who say Australia - the sixth-largest country in the world geographically and with the seventh-lowest population density - could afford to show more compassion to asylum seekers and is obliged to do so under a UN convention.

The government, supported by the main opposition, argues boat journeys are dangerous and controlled by people-smugglers. It says its policies have restored the integrity of Australia's borders, prevented deaths at sea and discouraged people who aren't genuine refugees from making the journey.

It becomes still more complicated by the question of who should bear the responsibility in medical emergencies for those awaiting processing.

Canberra's reluctance to grant medical evacuations is not confined to problematic pregnancies. It has also been the case for refugees needing other treatment, such as an 11-year-old Iranian boy who was prevented from going to Australia for corrective surgery on a broken arm in 2015, despite a storm of protest.

Australia-based activist groups Doctors for Refugees and the Refugee Action Coalition say the government's delayed action over Dee was based on a fear of her remaining in Australia after her procedure, and showed again that the government was ready to put lives at risk to make a political point.

It was not immediately clear if her condition had changed before she was airlifted on Friday.

Doctors for Refugees President Dr Barri Phatarfod said Dee had been identified by a team of several Australia-based specialists assessing her medical tests as a high-risk patient requiring urgent transfer to Australia in December. But, Dr Phatarfod said, approaches to Australia's Immigration Minister Peter Dutton had been rebuffed.

"Either the minster, who is not an obstetrician, chose not to believe us, which would take a certain amount of arrogance, or else the government just doesn't care," Dr Phatarfod told the BBC.

"This is a very high-risk pregnancy, which requires medical assistance that simply cannot be provided on Nauru. The Australian government is putting politics above people's lives.

"Nauruan women with complicated pregnancies are allowed to be flown to Australia. But because Dee is a refugee, she's effectively a prisoner. Her choices have been taken away. She'll be delivering how the Australian government says she'll be delivering."

Dr Phatarfod said despite promised funding from Australia to upgrade the Nauru hospital, the facility was still grossly inadequate for cases such as Dee's and operated by poorly trained staff.

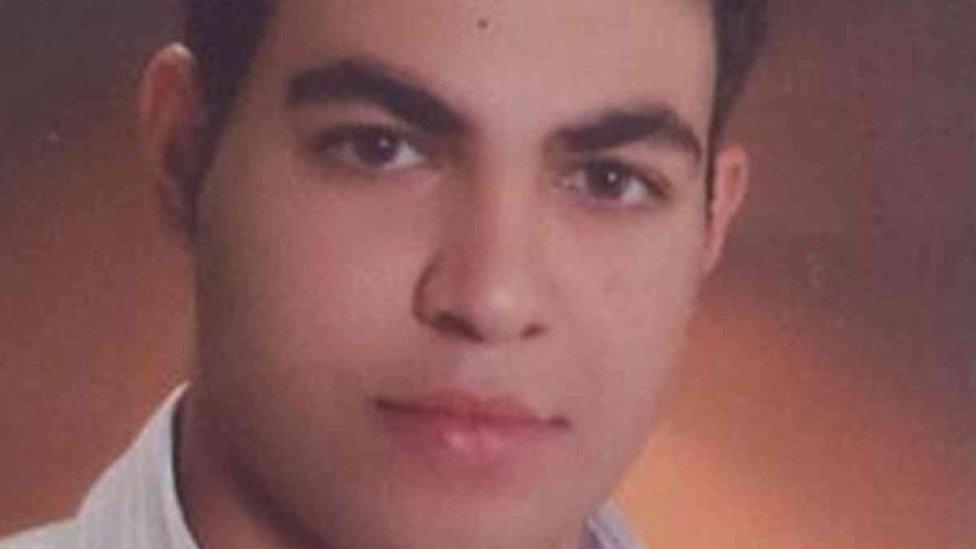

Asylum seeker Hamid Kehazaei died from a bacterial infection in 2014

She said the woman also had a large fibroid, or benign tumour, on the front of her uterus. Cutting through such growths for a caesarean delivery usually resulted in substantial bleeding, and Dr Phatarfod said the Nauru hospital was not equipped to handle transfusions.

This issue has been in the spotlight in the past few years through several high-profile cases, including:

Iranian asylum seeker Hamid Kehazaei, 24, who contracted a bacterial infection on Manus Island that ultimately led to his death in 2014. He was flown unconscious to Brisbane, four days after first complaining of being ill, external, where he later died.

A baby known as "Asha", born in Australia to Nauru-based asylum seekers, was sent back to Nauru when five months old in 2015 despite dire warnings from Australian medical personnel about conditions there. She returned to Australia for treatment for burns last year, after which doctors refused to discharge her, saying Nauru was not a safe environment. The government eventually allowed her to stay, external in Australia under community detention arrangements.

A Sudanese refugee, 27, who fell and suffered a seizure at the Manus Island centre before being airlifted to Australia, where he died in hospital, external. Refugee advocates said the man had suffered several collapses in the months before his death.

Also in 2016, a Somali refugee and her newborn infant were evacuated from Nauru in a critical condition and placed on life support in a Brisbane hospital after she gave birth, external, by caesarean section, one month prematurely.

"After that [the Somali refugee's] case, who in their right mind would take this risk with this latest case?" said Sydney-based Refugee Action Coalition spokesman Ian Rintoul.

"People on Nauru are hostage to politics. And Australia's two big political parties (Liberal and Labor) are both hostage to the offshore solution. There's no principled position by the two main political parties anymore."

Australia's offshore detention policies have been the subject of protests

Australia's Department of Immigration and Border Protection has kept its statements on the case brief. Handling media enquiries via email, it said it did not "provide specific details on the health and transfer arrangements of individuals".

"Australia provides comprehensive medical support services to the regional processing centre in Nauru and to the Nauruan Government Health Facilities," a spokesman wrote in an email to the BBC.

"Refugees in Nauru are eligible to access the Government of Nauru Overseas Medical Referral process if required medical services are not available in Nauru. This process is under the management of the Government of Nauru.

"Decisions relating to medical treatment, including medical transfers, for refugees in Nauru are made at the discretion of the Government of Nauru."

In a statement late on Thursday, Nauru's government said it had "no control over decisions by Australia on who to transfer".

"Within the last 30 minutes we have received confirmation from Australia that the patient [Dee] will be airlifted and this is expected to happen tomorrow," it said in a statement.

Nauru's government and Mr Rintoul confirmed Dee had boarded the plane early on Friday afternoon. Australia did not comment on Friday.

The Refugee Action Coalition says there are 1,800 people who have been determined to be refugees on Nauru and Manus. Australia's agreement with the US is for it to take up to 1,250 of them, although President Donald Trump's criticism of the deal means it is far from certain.

Even if all 1,250 were resettled, Mr Rintoul says this would still leave 550 in limbo on the Pacific islands, and continuing debate over their care.

- Published2 February 2017