How a child's exhumation has distressed Aboriginal elders

- Published

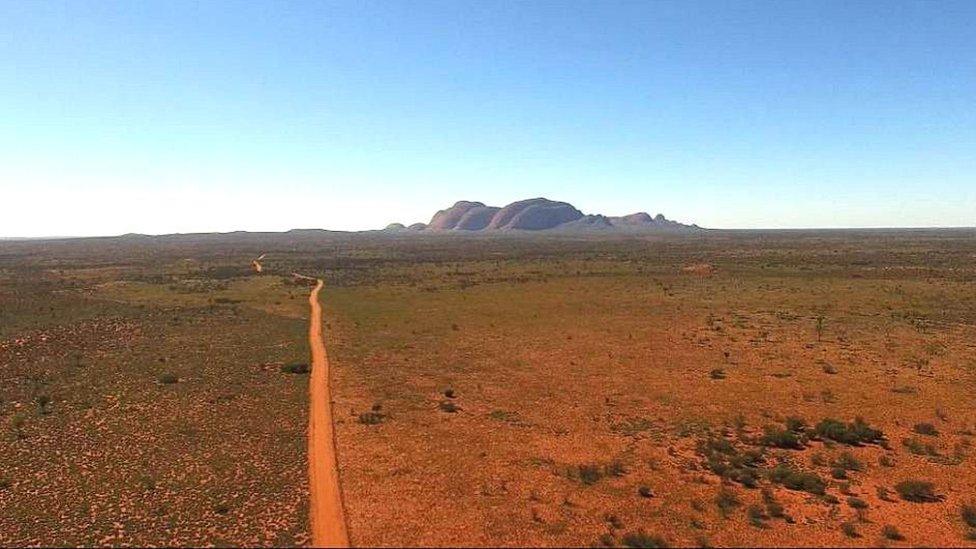

The Aṉangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara area, in South Australia's remote north

The removal of a child's remains from a cave in South Australia has prompted calls for an inquest, and government efforts to atone for culturally insensitive actions, reports Trevor Marshallsea.

Long ago, according to a famous Aboriginal legend, a maku - the white moth larva also known as the witchetty grub - made its way across the remote South Australian outback, carving what's now known as the Everard Ranges in its wake.

In the 1950s and '60s the British government, under agreement with Australia, exploded nine nuclear bombs near the region, as it developed its Cold War arsenal instituted under Winston Churchill. Two bombs were tested at Emu Field, just 180km (112 miles) across the flat, barren landscape from the Everards.

At some point during those controversial 11 years of atomic testing, an indigenous couple of the area and their young daughter took ill. Present day tribal elders believe this was due to radiation. They were of the so-called Spinifex People, who roamed over hundreds of kilometres in a nomadic existence in the outback.

The child died and her remains were interred in the customary manner for children, wrapped in hair and selected vegetation and placed in a high-up wall cavity in a cave. The parents soon also died, elsewhere in the region.

A decade later, relatives looked for the child's grave site, but with only scant details passed down from her parents, they were unsuccessful.

For some 60 years the bones lay untouched - until last November.

New land management staff on a routine inspection in the Sandy Bore Indigenous Protected Area (IPA) found the skeleton of the girl, thought to have been between three and six. Though indigenous people were present, they were not traditional owners of the area, and knew nothing of the girl's interment six decades earlier, and so police from the nearby town of Mimili were informed of the find. Also informed was a senior Aboriginal elder of the region, Rex Tjami.

Mr Tjami is director of administration in the Aṉangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara (APY) area. He also happens to be one of the relatives of the deceased family who searched fruitlessly for the girl's remains in the Everards that day, saying he looked to the north of the maku's trail, when the burial site was to the south.

When Mr Tjami went to the cave, which is deemed a sacred site, some three weeks after being informed, he was horrified to find the bones had been removed.

Mimili police had informed detectives in the state capital Adelaide, 1,400km to the south. A forensic pathologist and a forensic anthropologist had visited the site. The pathologist formed the view the bones might have been laid to rest within the past 10 years, and might even not be indigenous. As a result, he gained permission from the state coroner to take the bones and burial effects back to Adelaide for further examination.

That might sound like routine police work, but it has raised a huge storm of cultural controversy and calls for an official inquiry, having inflamed indigenous sensitivities on the issue of how Aboriginal Australians bury their dead.

Read more:

"Our elders are very upset," Mr Tjami told the BBC. "Our culture has some special ways when it comes to burials. Babies and children are buried in a very special way. This was very disrespectful."

Mr Tjami is incensed he was not consulted before the bones were removed. Not only were they in an IPA, he could have told the pathologist about the deceased parents and the child.

He said the removal of the bones was akin to "coming into someone's backyard" and taking something away. The APY strongly believe that the dead should be left in peace, so that their spirit is undisturbed. While that's similar to many cultures, indigenous Australians also have a strong connection to the land they are from, with a deep belief they must return to it when they die.

"A lot of people are very upset, especially the women. They want this child to 'come home'," said Rosanne McInnes, a barrister and former magistrate representing the APY. "What they say is that 'the mother is crying and calling for the child'. The women also regard this child as one of their own."

Ms McInnes is putting the case for a coronial inquest into why the remains were removed without proper processes respectful of the indigenous community. The case includes a sworn affidavit from Mr Tjami detailing his recollections about the deceased parents and child, including that they "came from the area where there was nuclear testing''.

.jpg)

A concrete tablet marks a spot where nuclear testing took place in South Australia

"We want protection for our heritage ... not people from Adelaide digging up old graves and taking away the bodies of our people without telling us," Mr Tjami says in his affidavit.

Ms McInnes is also petitioning the federal government to enshrine tighter protection for the APY area. She says this is needed as some "younger people" in the poverty-stricken region, in the far north of the state, have suggested making the burial site a tourist attraction, since the case has made headlines across Australia.

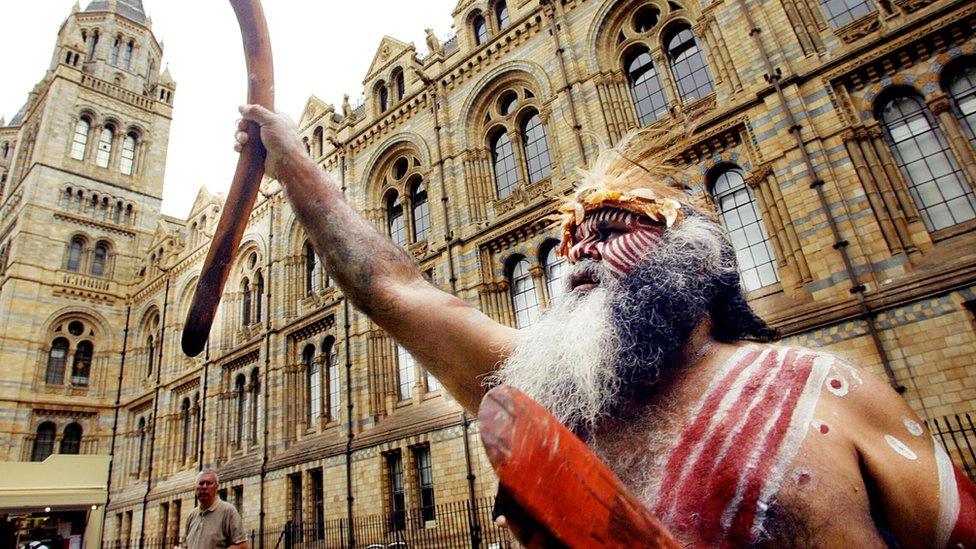

The episode again raises the issue of the battle to have Aboriginal remains returned, external to their place of origin, which continues to be fought internationally. Since 1990, the remains of 1,150 indigenous Australians have been returned to their homelands from abroad. But campaigners say 1,000 more are still held in museums around the world, mostly in the UK, Germany, France and the USA, and should be returned home for a proper burial.

Ms McInnes said still more remained in Australian museums and warehouses.

"They were found by road crews and railway crews and so forth and taken away and they're still sitting in warehouses somewhere in the cities," she told the BBC. "The indigenous people want to get their people back home, but how? They can't afford it."

Coroner orders report

The case of the Sandy Bore girl has at least prompted a swift response from authorities.

Coroner Mark Johns has ordered a comprehensive report from police, which will likely determine if an inquest will be held. He told the Adelaide Advertiser newspaper he had asked for details on how the discovery was made and how the remains were removed, to see if "things should have been done differently".

He had also asked for a report on why the pathologist and anthropologist had formed the view the remains might not be historic.

Ngarrindjeri elder Major Sumner calls for remains to be returned from Britain to Australia in 2003

The South Australian government has expressed its regret over what's been called another indignity for a child assumed to have been killed by radiation sickness. State Aboriginal Affairs Minister Kyam Maher has also called on the coroner to review policies about the removal of bones from sacred burial sites for examination "to avoid any future incident that may cause this type of distress".

While the coroner still awaits his report from police, he has ordered the remains to be released and returned to the cave within two weeks. Mr Maher said the government would cover the costs of reburying the remains, including a proper Aboriginal funeral.

Britain detonated nine nuclear devices in the region between 1952 and 1963, seven in the Maralinga area and two in nearby Emu Field. Indigenous people plus UK servicemen, Australian soldiers and civilians were exposed to radiation, with various illnesses resulting. The site, of some 1,800 sq km, was officially closed to human habitation in 1967, but handed back between 2009 and 2014 after clean-up operations.

In 1994, the Maralinga-Tjarutja people were paid A$13.5m (£8.2m; $10.3m) in compensation under a deal between Australia and Britain after a 1985 Royal Commission into the nuclear tests.

- Published31 December 2014