Sydney's controversial bar curfews: Have they worked?

- Published

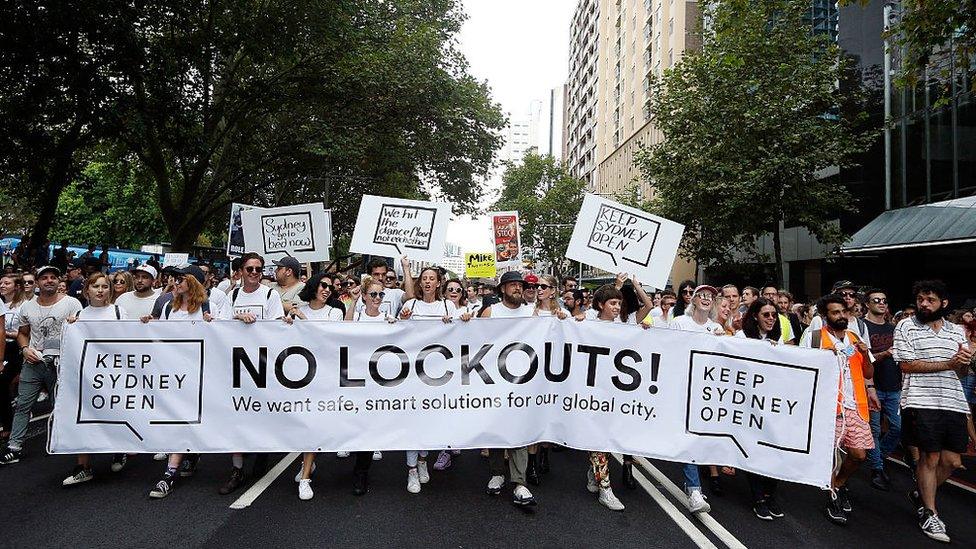

Sydney's controversial lockout laws have triggered protests

One evening in January, the owner of an exclusive Sydney nightclub received a call from Bruce Springsteen's manager.

"They'd just finished a promotional thing and he asked me if he could bring the band over for a few drinks. I told him no, we have lockouts and we're about to close.

"He then asked me where else they could go, and I literally said I don't know, everything's closed or closing soon. I was really embarrassed."

Sydney's "lockouts" are a raft of laws and interventions geared at reducing alcohol-related harm at licensed premises across the state of New South Wales (NSW).

They were introduced in January 2014 to placate public concern over alcohol-related violence that seemed to be spiralling out of control - most infamously following the tragic deaths in the Kings Cross entertainment district of two 18-year-old men who were "coward punched" in separate, random acts of violence.

The laws include things like better staff training and temporary banning orders for troublemakers.

Most controversially, the lockouts include a curfew that stops patrons from entering or re-entering licensed venues after 01:30 and a 03:00 "last drinks" regime. Only two venues - both casinos, one of which is under construction - were granted exclusion.

Do the ends justify the means?

Three years later, evidence shows the lockouts are working.

The laws were enacted in response to high-profile cases of violence

"There's been a dramatic drop in assaults in Kings Cross and the CBD [Central Business District] and no spill-over anywhere else," says Don Weatherburn, director of the NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research, citing a 45% drop in non-domestic assaults in Kings Cross and a 20% drop in the CBD since 2014.

"Before in Kings Cross we had a social environment we called toxic that was directly translating into violence," adds Dr Nadine Ezard, clinical director of alcohol and drug services at St Vincent's Hospital in the inner suburb of Paddington, where bloodied victims were regularly carted in on weekends until the lockouts came into effect.

Voters also back the lockouts. A March poll on SurveyMonkey found 65% of respondents were supportive of them, while nearly 60% backed them in a recent Fairfax newspaper poll.

But the peace and quiet has come at a price. Combined with heavy-handed policing, the lockouts have seen a reduction of night-time foot traffic in Kings Cross of up to 80% and the concurrent closure of dozens of licensed venues and interdependent businesses.

The late-night economy of Oxford Street, Sydney's world-famous LGBT entertainment district, has suffered a similar fate, as have parts of the CBD.

The famous Kings Cross district has been among the worst affected areas

"Before the lockouts, I was running Spice Cellar, a very successful live music venue in the city," says Murat Kilic. "We brought in performers from all around the world. We never had an incident in three years.

"Then the lockouts came and within a year revenue dropped 60%. We had to close the business and let go of 20 staff and all our contractors.

"It's pretty much unanimously accepted in my industry that nightlife in Sydney has been obliterated. It is financially untenable for most late-night venues to stay in business."

'What are we, children?'

Ron Creevey, owner of The X Studios, the largest licensed premises in Kings Cross, has a similar story.

"The lockout is costing me about A$200,000 (£123,000; $150,000) a month," he says.

"But it's not just what it did to me. Thousands have been affected. They were hard-working people.

"My heart bleeds for the families of those two kids who were killed. But there's no logical reason to penalise bar owners in a certain geographical area because of something that happened on the street. In Sydney we can't even buy a bottle of wine at a liquor store after 10pm. What are we, children?"

Gary Friedland, a nightlife photographer whose business is down 50% since 2014 describes the lockouts as an "underhanded form of prohibition".

"What they do is the police hassle venues until they close down. Look how they raided Candy's Apartment," he says, referring to a December event that saw a busload of police in riot gear and sniffer dogs close off an entire street to raid a Kings Cross nightclub.

When drugs were found on one patron, 3,000 others were booted out onto the street and Candy's Apartment was slapped with a 72-hour closure on one of the busiest weekends of the year.

Advocacy group Keep Sydney Open has been vocal in its opposition

"To call this prohibition is not an exaggeration," says Tyson Koh, campaign manager of anti-lockout advocacy group Keep Sydney Open.

"I have sat around tables with people from vocal health lobby groups like St Vincent's Hospital that have a very clear agenda to restrict the sale of alcohol whenever and wherever possible. They have made it very clear they have no interest in the culture or nightlife of the city."

The party goes underground

Allegations of a secret prohibitionist government agenda were fuelled last year when former state premier Mick Baird posted an impassioned defence of the lockouts on Facebook.

"Now, some have suggested these laws are really about moralising. They are right. These laws are about the moral obligation we have to protect innocent people from drunken violence," Mr Baird wrote in a post that saw him nicknamed "Casino Mike" by the anti-lockout lobby.

But media director at St Vincent's David Faktor, who describes Keep Sydney Open as a fringe group, says talk of prohibition is nonsense.

"No-one wants to live in a nanny state and I don't think anyone at [our hospital] has a prudish or nanny-ish mentality or philosophy," he says. "We were just concerned about the level and volume of violence we were witnessing and that [Australians] have a problematic relationship with alcohol.

"The idea to compare us to Spain or parts of Asia where you can buy alcohol at any time of the night and everyone gets along does not work here, because they don't have the same extent of problems as we do."

Former premier Mike Baird depicted as "Casino Mike" in a Sydney street mural

St Vincent's Dr Ezard disputes arguments that Sydney's nightlife is on life support, saying the city is awash with licensed premises. But she concedes that if young people feel they are living under an prohibitionist regime then "we need to listen to them".

"We know from our experience that much of the drug-related harm is a result of its illegal status," Dr Ezard says. "I would be very reluctant to use any harm-reduction method that feels like prohibition because we know that be making substances illegal it creates greater harm."

'You can't stop the party'

Yet Sydney has been exhibiting symptoms of prohibition for years. "There are big warehouse parties every week in city fringe areas. I would guess anywhere from 10 to 20 ranging in size from 100 to 1000 people at each," says a patron who spoke on condition of anonymity.

"It's all underground and the biggest thing going on right now in Sydney," adds Mr Creevey of The X Studios. "If you can't provide a safe environment for people to party, they'll go elsewhere. You can't stop the party."

Jess Scully, one of 10 elected councillors in the City of Sydney and perhaps the most high-profile anti-lockout advocate within the establishment, concurs, saying lockouts have "criminalised a cultural expression" and the "right to party".

But she discounts conspiracy theories about protectionist agendas, saying the laws were set up with good intentions. "There's no big conspiracy, it's just bad policy that's all - a blunt legal instrument used to fix a social problem," she says.

New Premier Galdys Berejiklian has given no indication she will change tack

Ms Scully says trains stopping at midnight prevented people getting home from Kings Cross, so they congregated on the street in numbers. "We can't legislate it out of existence [and] just push it to unsafe areas where we can't manage it, like warehouse parties," she warns.

Lockouts of the future

In December, just before retiring, Mike Baird announced that three live music venues in the CBD will be granted an additional half hour of trading time, moving the curfew to 02:00. Applications for curfew extensions for another 17 similar venues were being processed.

Coupled with the arrival of new Premier Galdys Berejiklian, a former transport minister who oversaw a much-needed infrastructure boom in Sydney and who promised voters a more consultative approach, hopes were high among the anti-lockout camp for a rethink.

The premier's office did not reply to requests for an interview, though a spokesperson for Minister for Racing Paul Toole, who oversees liquor licensing in NSW, told the BBC the new administration's approach to lockouts would be "business as usual".

Ms Scully believes that would be a mistake.

"They have a golden opportunity to redefine the problem and look at it from a design point-of-view," she says.

"If we could get people from the hospitals and police and licensees listening to one another it would be great, but right now everyone is in a combative mind frame. It's all gotten personal, and that makes everyone very emotional and defensive, and that is not a way to good policy outcome.

"But whichever way you look at it - lockouts are unsustainable. You can't say Sydney is a global city where tourism is one of the main economic drivers and then have Bruce Springsteen going home and telling everyone he couldn't get a drink after midnight."