How Australia's A$49bn internet network came to be ridiculed

- Published

The rollout of Australia's National Broadband Network has been heavily criticised

In 1872, rugged, frontier Australia was lauded for overcoming the tyranny of distance to connect itself to the world via the "bush telegraph", a two-year project stringing 3,200km (2,000 miles) of wire through the outback that became part of the nation's folklore.

By contrast today, while striving to be seen as an "innovation nation", Australia stands condemned, even ridiculed, for its latest drive for connectivity: a modern, fast internet network.

Three letters - NBN - have come to strike dread into the minds of consumers, with the National Broadband Network symbolising for many a template in how not to do things.

Given Australia's large size and sparse population density of three people per square kilometre, the NBN is the country's largest ever infrastructure project.

The total budget sits at A$49bn (£29bn; $38bn). Of that budget, around 35% must be spent connecting the final 10% of users, including wiring to remote areas, erecting many of the required 2,600 wireless towers and, most expensively, putting two satellites in the sky.

This week, Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull called the NBN a mistake and a "calamitous train wreck" by a previous Labor government. Former Prime Minister Kevin Rudd hit back by saying the project's issues "lie all on your head" - meaning the current conservative government.

The escalating blame game, the NBN's slow roll-out, and a switch to inferior technology midstream have combined with other factors to leave Australians frequently asking the question: Why is our internet so slow?

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

In 2013, Australia ranked 30th for average internet speeds. The NBN was meant to improve that, but the most recent standings ranked Australia 50th.

The State of the Internet survey by US internet firm Akamai put Australia - with an average of 11.1 Mbps (megabits per second) - behind countries including Kenya, Hungary and Russia. And while it promotes itself as part of go-ahead Asia, Australia sits only eighth in the region, behind neighbours such as Thailand (21st overall) and New Zealand (27th).

Some comparisons are misleading. Only 1.75% of Kenyan homes have fixed-line internet, compared with 90% in Australia. For many, particularly inner-city Australians on the best NBN technology, fixed-line speeds are adequate, particularly if you pay more.

But there's no escaping Australia has been overtaken by many countries on the internet table.

What's worse is that with many of those connected to the NBN reporting no improvement over old ADSL connections, of the homes equipped to take the new service, only 40% have chosen to do so. In business, and international competitiveness, the fears are perhaps more serious.

"Going lower in ranking is alarming, and just not acceptable," says University of Sydney academic Dr Tooran Alizadeh, who has researched the NBN extensively and, like others, worries Australia's best minds will be lost to countries with better technology.

"Australia wants to be in the first 10 or so economies in the world. Obviously if you want to do that your internet access cannot be ranked 50th."

The history

In 2007, Mr Rudd announced 98% of Australian homes would be on the NBN by 2020. It was a breathtakingly ambitious idea. It was also, according to critics, backed by inadequate research into logistics and costs, initially put at A$15bn.

The natural starting point was Australia's oldest telecom company, Telstra. Elsewhere, countries like New Zealand simply used the infrastructure already laid by their major telecom company to install fast internet cabling. But Telstra, halfway privatised at the time, clashed with regulators over how it might onsell broadband access to its competitors, and so pulled out of the running to build the network.

Eventually, the government announced it would simply start a whole new semi-autonomous company from scratch. Called the NBN, it would set up the infrastructure to connect Australians with state-of-the-art fibre optic cables to their homes, selling bandwidth wholesale to retailers.

Progress was slow, sporadic, and expensive.

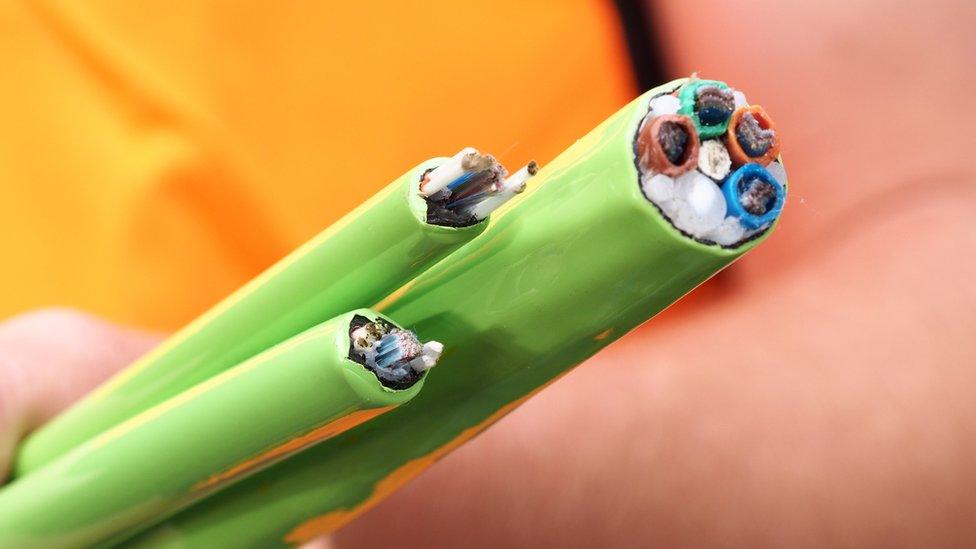

With Australia's preference for underground wiring, often concrete driveways would have to be dug up and relaid. Costs thus blew out for connecting houses from an envisaged average of A$4,400 to, in some cases, more than A$20,000, an NBN spokesman says.

A rocket carrying the NBN's first satellite is launched into space from French Guiana in 2015

Complaints soon arose over why some regions were connected before others, with schools and hospitals, for example, getting very unequal standards of internet quality. Accusations of government pork-barrelling, however, were wide of the mark.

"The government just wanted progress, so it became a matter of which places were easiest and quickest to connect," one source with intimate knowledge of the subject told the BBC. "Often this came down to issues like basic geology - where was the rock easiest to drill through?"

After the conservative government attained power in 2013, the NBN struck more upheaval, with copper wire ordered for the final stretches of connection, surrounding neighbourhood broadband nodes.

This presents a slower connection to the twice-as-expensive fibre optics. It also means residents, say 400 metres from the node, will have slower internet than a neighbour a few doors away. Critics also charge it's a false saving, since copper wire needs replacing far earlier than fibre optics.

Complaints and competition

Then came the NBN's high pricing to retailers, who buy limited supply to pass on to consumers, which leaves so many Australians staring in frustration while buffering or, worse still, service drop-outs occurring each peak hour.

"NBN has worked hard to bring the cost of bandwidth down but we cannot fill the pipes ourselves - it is up to the retailers to make sure that they are buying enough capacity to deliver a good quality of service," an NBN spokesman told the BBC.

Yet another complication is the number of retailers - 180 - making it hard for the NBN to police quality control for end users.

"We've had huge problems getting our house connected to the footpath node," says Matt Grant, a factory manager in suburban St Clair, just 39km from central Sydney. "But when I complained to the retailer, they told me to talk to the NBN. When I talked to the NBN, they sent me back to the retailer."

He was eventually connected, but said "it's no better than we had with ADSL, especially in peak times".

Last week, Australia's Telecommunications Industry Ombudsman revealed there had been a 159% increase in NBN-related complaints in the last financial year.

NBN chief executive Bill Morrow told the Australian Broadcasting Corp, external this week that it "turns [his] stomach" that some customers were being left behind, but he placed blame on retailers, and said the government would ultimately decide when to replace copper connections. He also noted increasing competition from mobile broadband technology.

"Look, it is a competitive environment, but I just want to repeat we are doing everything we can to ensure the NBN delivers a great service," he said.

The network says it's still on target to have 98% of homes connected by 2020, but Australia's internet malaise will still take some solving.

There's hope of improvement, but not until base prices can come down as the NBN gradually recoups its massive expenditure. And despite the political finger-pointing, Mr Turnbull's government insists the network will be "fit for purpose".

"Australia needs a 21st Century broadband network and this is not being delivered," said Laurie Patton, executive director of consumer advocacy group Internet Australia.

"The way we're heading now, whoever is in office in 2020 will have to deal with our biggest ever national infrastructure debacle."