Manus Island: Refugees refuse to leave Australian camp amid safety fears

- Published

Refugees at the Manus Island detention centre say they fear attacks by locals

Refugees held by Australia in Papua New Guinea (PNG) have barricaded themselves inside a detention centre and launched legal action to fight its closure.

Detainees, fearing for their safety after crowds reportedly gathered chanting "don't come out", argue that closure will breach their human rights.

Australia holds asylum seekers arriving by boat in camps on PNG's Manus Island and the small Pacific nation of Nauru.

The Manus Island centre is due to close after it was ruled unconstitutional.

But many of those in the camp argue that its closure, ordered by a PNG court and initially scheduled for Tuesday, will deny them access to water, electricity and security.

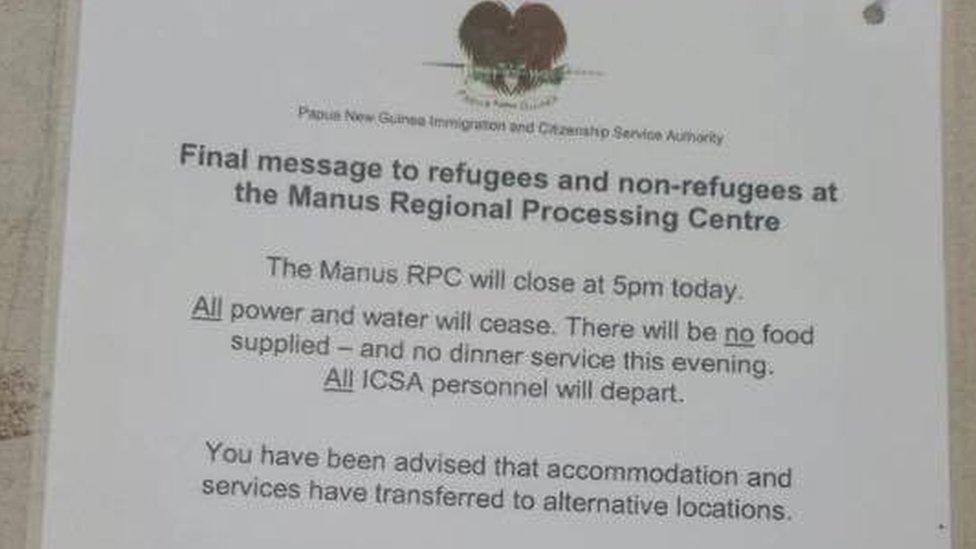

The local authorities said these provisions would cease at 17:00 local time (07:00 GMT), and that PNG defence authorities could enter the centre as early as Wednesday.

Staff have reportedly abandoned the camp. Lawyers for some of the detainees filed a last-minute lawsuit in PNG to prevent the camp's closure. A ruling is expected on Wednesday.

A notice telling detainees that water and power will be cut off

Refugees told the BBC that detainees planned to protest peacefully, and had begun stockpiling water and dry biscuits, as well as setting up makeshift catchments for rainwater.

They claimed that local residents began looting the compound on Tuesday after security guards left.

Behrouz Boochani, a journalist and Iranian refugee who has been held on Manus Island since August 2014, wrote on Twitter that a big part of the compound had no access to power, and refugees were suffering from fear, stress and hunger.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

Conditions for the refugees were unbearable, said Nick McKim, a senator with the Australian Greens Party who is on Manus.

"I can only describe what is happening on Manus now as a humanitarian emergency," Mr McKim told Reuters. "It is 31C (88F) today and drinking water will be cut off."

Under a controversial policy, Australia refuses to take in anyone trying to reach its territories unofficially by boat. They are all intercepted and held in the Nauru and Manus Island detention centres.

Why don't refugees want to leave?

About 600 men have been told to leave the camp, but many have reportedly barricaded themselves inside due to fears for their safety if transferred to temporary accommodation in the Manus Island community.

The news has raised concerns of a possible siege at the facility.

"Navy and police [are] heavily armed, but we don't know who they want to go to war with, locals or refugees. So scary," tweeted Mr Boochani, external.

Last week, Human Rights Watch warned that the group could face "unchecked violence" by local people who had attacked them in the past - sometimes with machetes and rocks.

Where would they go?

Canberra has consistently ruled out transferring the men to Australia, arguing it would encourage human trafficking and lead to deaths at sea.

However, PNG has said it is Australia's responsibility to provide ongoing support for the detainees. The Australian government says PNG is responsible for them.

The refugees can permanently resettle in PNG, apply to live in Cambodia, or request a transfer to Nauru, but advocates say few have taken up these options.

Some men already in the temporary accommodation were "comfortably accessing services and supports there", Australia's Department for Immigration and Border Protection said on Tuesday.

There have been protests in Australia against the Nauru and Manus Island detention centres

A separate resettlement deal struck with the Obama administration in 2016 saw the US agree to take up to 1,250 refugees from the PNG and Nauru centres.

Last month, a group of about 50 people from the detention centres became the first to be accepted by the US under the agreement.

The agreement, which is being administered under the United Nations refugee agency UNHCR, is prioritising women, children and families and other refugees found to be the most vulnerable.

However, the US has not given an estimate of how long the application process will take and it is not obliged to accept all of them.

How will the closure affect detainees?

Greg Barns, a lawyer assisting with the legal action, said the closure would breach rights enshrined in PNG's constitution.

"The men are vulnerable to attacks and physical harm so we are seeking to ensure their constitutional rights are not breached and there is a resumption of the basic necessities of life," he told the BBC.

"The men have been dumped on the street, literally. What is going on is unlawful."

Australia's detention centre in Papua New Guinea is due to close on Tuesday

The application also seeks to prevent the forcible removal of the men to an alternative centre on the island, and calls for them to be transferred to Australia or a safe third country.

'Australia's Guantanamo'

Australia first opened Manus Island centre in 2001. It was closed in 2008 and re-opened in 2012.

Six asylum seekers have died since 2013, including Iranian man Reza Barati who was murdered during a riot.

Earlier this year, the government offered compensation totalling A$70m (£41m; $53m) to asylum seekers and refugees detained on Manus Island who alleged they had suffered harm while there.

The lawsuit alleged that detainees had been housed in inhumane conditions below Australian standards, given inadequate medical treatment and exposed to systemic abuse and violence.

The government called the financial settlement "prudent", but denied wrongdoing.

- Published30 October 2017

- Published18 October 2017

- Published30 October 2017