How Australia's extreme heat might be here to stay

- Published

Warmer seas are turning Great Barrier Reef turtles female, a study has found

A section of highway connecting Sydney and Melbourne started to melt. Bats fell dead from the trees, struck down by the heat.

On the northern Great Barrier Reef, 99% of baby green sea turtles, a species whose sex is determined by temperature, were found to be female.

In outer suburban Sydney, the heat hit 47.3C (117F) before a cool change knocked it down - to the relative cool of just 43.6C in a neighbouring suburb the following day.

Scenes from a sci-fi novel depicting a scorched future? No, just the first days of 2018 in Australia, where summer is in fierce form.

With parts of the US suffering through a particularly grim winter, extremes in both hemispheres have triggered discussions about the links between current events and the build-up of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere.

Climate change 'no brainer'

The climate system is incredibly complex and no weather event can be directly attributed to rising emissions, but everything that is experienced today happens in a world that is about one degree warmer than the long-term mean.

Prof Andy Pitman, the director of the ARC Centre of Excellence for Climate Extremes at the University of New South Wales, says given the average temperature has risen it is a "no brainer" that the likelihood of the sort of heat that hit Sydney last week has also increased.

"It was a meteorological anomaly, but the probability works a bit like if you stand at sea level and throw a ball in the air, and then gradually make your way up a mountain and throw the ball in the air again," he says.

"The chances of the ball going higher increases dramatically. That's what we're doing with temperature."

Sydney has experienced a sweltering start to 2018

While it is record-breaking that tends to make news, scientists say it is the unbroken run of hot days in the high 30s and 40s that causes the significant problems for human health, and other life.

Health officials in Victoria highlighted the threat of heatwaves when they found about 374 more people died during an extreme three-day period in January 2009 than would have been expected had it been cooler.

There has, however, been relatively little investment in research into the health impact of escalating maximum temperatures.

A paper published in the journal Nature Climate Change last year said while a government report called for greater focus on the area 25 years ago, less than 0.1% of health funding since has been dedicated to the impact of climate change.

Prof Pitman says Australia is yet to properly consider the health risks of a warming planet.

"It's not being able to cool down at night, and in the days that follow, that causes problems," he says.

"I was camping in the Blue Mountains [west of Sydney] on Saturday night. It was about 30 degrees at midnight, and I could feel my heart racing. Now, that extra stress on my cardiovascular system didn't kill me, but it might have if I was 20 years older."

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

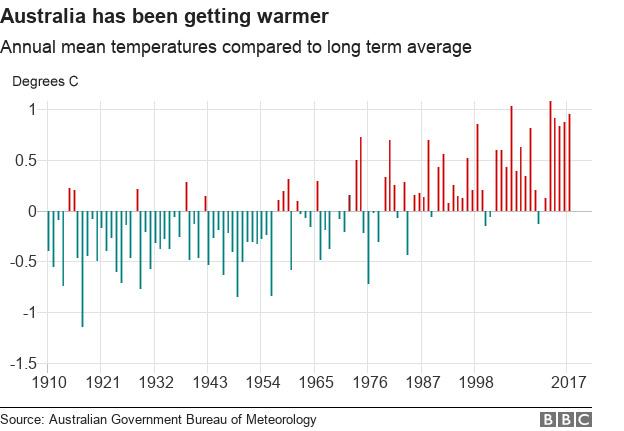

Last year was Australia's third-warmest year since records began, according to the Australian Bureau of Meteorology.

Globally, it was the second or third warmest, and comfortably the hottest year in which there was not an El Niño weather system helping push up temperatures further.

Put another way: it is now hotter without an El Niño than it was with an El Niño just a few years ago.

Far-reaching impact

In eastern Australia - where the bulk of the population lives - temperatures were particularly inflated during summer months, when an increase is most likely to lead to uncomfortable or dangerous heat.

Several locations had runs of record hot days and nights. More than 40% of the most populous state, New South Wales, recorded at least 50 days hotter than 35C. The town of Moree had 54 consecutive days of extreme heat.

"Across Australia, the last five years were all in the top seven years on record. That's quite a striking signal," the Australian Bureau of Meteorology's Dr Blair Trewin says.

The extra energy warming up the climate system is also being felt in several ways. The bushfires season starts earlier than it used to, and Australia has already experienced wild blazes this season.

A bushfire tears through South Australia last week

Along with the increased background heat, this is in part due to a clear drying pattern in some areas.

Rainfall is down for both the south-east and south-west of the country in the cooler months months between April and October.

"That also has quite significant impacts for agriculture because historically that's when they get most of their inflows," Dr Trewin says.

The impact of warming on the World Heritage-listed Great Barrier Reef, the only living structure visible from space, has been well documented. Estimates suggest about half its shallow-water coral was killed during bleaching events over the past two years linked to increased water temperatures.

Further south, the sea along Tasmania's east coast has warmed dramatically, pushing tropical species to unlikely high latitudes and coinciding with the disappearance of giant kelp forests.

Some weather patterns have not changed. There is no evidence of variations in cyclone behaviour or the frequency or intensity of large hail and lightning, for instance.

Underwater video shows where bleaching has damaged the Great Barrier Reef

All this comes against a backdrop of political fighting over how to tackle climate change.

It is less than a year since senior government members brandished a piece of coal in parliament to taunt the Labor opposition, whom ministers accused of wanting to see an end to the fossil fuel industry.

The Malcolm Turnbull-led government remains committed to a 2030 target pledged at the Paris climate talks: a 26-to-28% cut below 2005 emissions.

It says it can cut emissions while shielding the public and business from unnecessary price rises. It also points out that Australia is directly responsible for little more than 1% of global emissions (though it is responsible for about 30% of the global coal trade).

But national greenhouse accounts released in the week before Christmas showed Australia's industrial emissions have been on an upward curve since 2014, when the government repealed carbon pricing laws, which required big business to pay for its pollution.

Emissions had fallen in the two years the laws were in place. The latest projections in the accounts suggest Australia will overshoot its 2030 target unless new policies are introduced to arrest the growth.

"There really isn't an argument that climate change isn't true in parliament anymore," Prof Pitman says. "You'd find a couple of members of parliament that say that, but you'd also find a couple who didn't believe in evolution and didn't believe in inoculating children against disease.

"The issue now is that the scale of concern - and the action under way or committed to both in Australia and internationally - doesn't match the scale of the problem."