Australia Catholic bishops criticise 'foreign influence' laws

- Published

Catholic bishops have raised concerns that new laws in Australia could force Church members to register as agents of a foreign power.

Last month, Australia unveiled legislation designed to limit foreign interference in political activity.

The government said the changes, still to be formally debated, will protect transparency and Australia's interests.

But Catholic officials have said the laws are too broad and could prevent churchgoers' advocacy and charity work.

"Catholics are followers of Jesus Christ - we are not agents of a foreign government," said Bishop Robert McGuckin, from Toowoomba in Queensland.

What are the new laws?

The wide-ranging restrictions would ban foreign political donations and force lobbyists to disclose overseas links on a public register. Failure to do so would be a crime.

It would also broaden the definition of espionage to include people who receive classified information without permission, rather than simply those who share it.

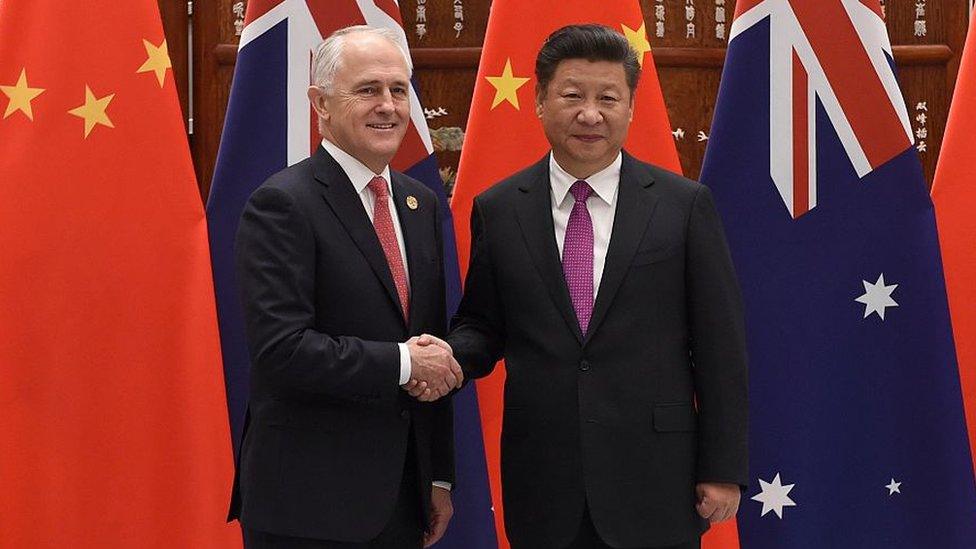

Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull said in December that the crackdown was not aimed at any country - although he noted recent "disturbing reports" of Chinese influence.

Some people say the students' complaints are organised

"Foreign powers are making unprecedented and increasingly sophisticated attempts to influence the political process, both here and abroad," he said at the time.

The legislation would also include several other measures aimed at preventing such activity.

What are the bishops' concerns?

The Australian Catholic Bishops Conference acknowledged the bill did not target Catholics specifically, but criticised it as having "extraordinary breadth".

It said terms in the bill such as "foreign principal" and "communications activity" were potentially open to wide interpretation.

Bishop McGuckin said it could result in Catholic churchgoers being classified as agents of the Vatican.

"It seems that every Catholic involved in advocacy may need to register and report," he told a parliamentary committee on Tuesday.

"Given Catholics make up more than the 20% of the population of Australia… we think that's a lot of registrations."

Have others been critical?

Yes. Media organisations, law groups and other organisations have expressed various concerns that freedoms could be restricted.

The Australian Human Rights Law Centre said charities and not-for-profit groups would find it "complex, cumbersome and costly" to comply with the transparency measures.

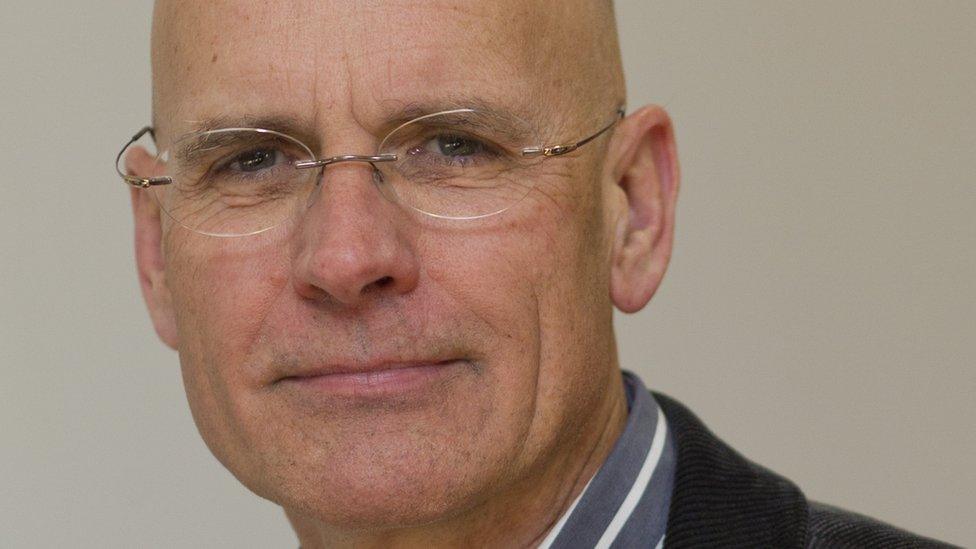

"Many organisations will simply opt out of electing not to speak up about their work and Australia's democracy will be much poorer for that," director Hugh de Kretser told the BBC.

The Law Council of Australia said the breadth of the bill could have "a chilling effect on public policy dialogue".

What do lawmakers say?

The chair of the Intelligence and Security Committee, Andrew Hastie MP, played down the concerns.

"I think if you're seeking to build Australia and not undermine it as an Australian citizen, then you shouldn't be concerned," he told the Australian Broadcasting Corp.

However, he did not rule out changes.

"We could introduce more safeguards if needed - I'm not convinced there is a need," he said.

Beijing has previously accused Australian politicians and media outlets of "hysteria" over the political influence debate.

- Published5 September 2017

- Published13 November 2017

- Published12 December 2017

- Published6 December 2017