Venice Biennale: The row over anointing Australia's entrant

- Published

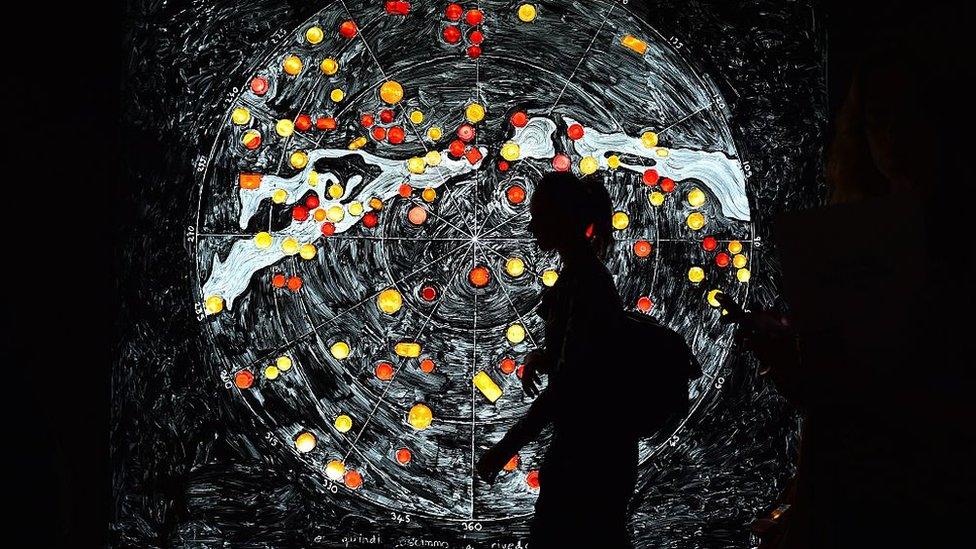

A work by Australian artist Fiona Hall at the Venice Biennale in 2015

A new method of selecting Australia's entrant for the world's biggest art event has set off a passionate backlash among some donors, reports the BBC's Hywel Griffith in Sydney.

There is no room for democracy when it comes to choosing Australia's leading artist, according to one of the country's most prominent philanthropists.

Simon Mordant has donated heavily to the arts in Australia over the last decade, including about A$3m (£1.7m; $2.4m) towards Australia's involvement in the Venice Biennale. But he and his wife Catriona have withdrawn financial support for next year's entry.

They made the decision after artists were told they would have to apply for the position instead of being invited.

"Most eligible artists who could do the job are extremely busy," Mr Mordant told the BBC's World at One programme.

"They are not going to respond to a newspaper advert and they are not going to want to be disappointed by not being selected."

'Peak of an artist's career'

The changes made by the Australia Council for the Arts also mean the role of commissioner will no longer by filled by an arts patron, and will be controlled by the council instead.

Mr Mordant, who was commissioner for the 2013 and 2015 Biennale entries, argues that the changes have been made without consultation, and could result in a poor selection.

Simon Mordant is a former Australian commissioner for the Venice Biennale

"I think representing Australia at the Venice Biennale is the peak of any Australian artist's career - it's not about democracy," he says.

"It's about selecting someone that you think represents Australia, and makes a statement about something today."

Mr Mordant is one of two prominent donors to withdraw their backing. But the Australia Council expects its changes to bring new philanthropic support.

The council says the process has been changed to comply with Biennale guidelines, and has resulted in expressions of interest from 70 artists currently being considered by a panel of experts.

The response within the wider arts community has been mixed. Some are concerned about upsetting wealthy donors, while others see it simply as a "stoush" among the arts elite.

For many aspiring painters at a fine art class in Sydney, the thought of representing their country is appealing.

"I love the idea, because maybe then I have the chance," says Monica Batiste. "I can give it a go - I would give it a go."

The Pavilion of Australia in Venice, where art is put on display

Student Elspeth McKellar, one portrait model in the class, says: "I do like the idea that anyone who calls themselves an artist has an opportunity.

"I feel it potentially can be a little bit of a closed world, so any little door that opens is a great thing."

But school teacher Tim Stinson isn't so sure, saying he believes "allowing anybody to apply for it" could undermine recognition that art practice - everything that goes into a person's craft - is a lengthy process.

The name of the artist chosen to represent Australia in next year's Venice Biennale is due to be announced by the end of March.

The Australia Council for the Arts says the calibre of entries it has received should "soundly put to rest" any concern that leading artists were deterred from taking part.