National Geographic apology: 'We were anticipated to be a dying race'

- Published

National Geographic has made an apology over its past coverage

Last Tuesday, US magazine National Geographic apologised for what it called decades of past racist coverage.

Among some examples, editor Susan Goldberg cited a photo caption from 1916, external that left her "speechless".

Beneath photos of Aboriginal Australians, it read: "South Australian Blackfellows: These savages rank lowest in intelligence of all human beings."

Such a statement reflected entrenched views of the era, indigenous Australian leaders told the BBC this week.

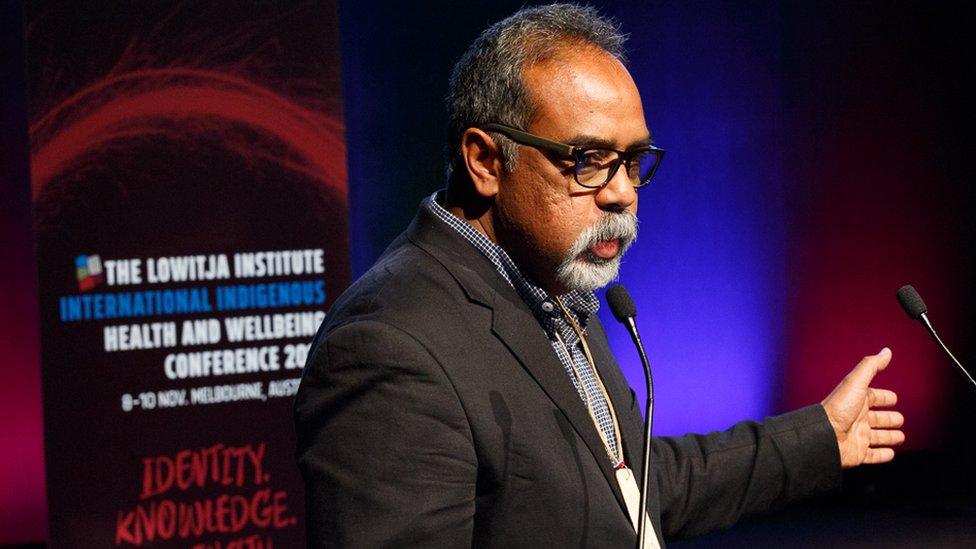

"This was a time when our people were denied access to lands, denied culture, language and were anticipated to be a dying race," said Romlie Mokak, head of the national Lowitja Institute for indigenous health research.

"So the language is not surprising at all - it is completely within the context of that period, as wrong as it is."

Rampant discrimination and denial of rights existed: Aboriginal Australians could not vote until 1962, and they were not counted in the national Census until after 1967. An infamous assimilation policy of removing children from their families persisted until 1970, creating what is now known as the Stolen Generations.

Romlie Mokak is head of the Lowitja Institute for indigenous health research

"For us as a nation, 1916 was not very long ago," said Rod Little, co-chair of National Congress of Australia's First Peoples.

"It's just unbelievable that people could treat other human beings like that - this indoctrinated belief of one race being superior to another."

The National Geographic example reflected a prevailing ideology, according to Karen Mundine, director of Reconciliation Australia.

"We were seen as somehow less than human, or at least less than European people," she said.

She welcomed the magazine's acknowledgement of its past wrongdoing, and the role it had had in reinforcing prejudice.

"It's positive that National Geographic has recognised there are problems with their previous depictions, and they are starting to address how they've spoken about people of colour," she said.

How about now?

While emphasising a clear distinction between the language of past and present eras, the leaders agreed that forms of racism persisted in contemporary media reporting and political discourse.

"It has been so wrong for such a long time that there are still elements of that [racism] which are very strong in our society," Mr Little said.

He cited recent attempts by conservative legislators to water down racial discrimination laws as an example. According to Mr Little, mainstream media can also paint a simplistic picture of Australia - one that sometimes ignores the hardships of minorities, or sensationalises their difference.

The government's annual Closing the Gap report has found that indigenous Australians continue to experience greater inequality than non-indigenous Australians.

One man's cross-country march for indigenous rights

A 2016 survey by Reconciliation Australia found that more than a third of Australians said their main source of information about indigenous peoples came from the media.

However, according to Ms Mundine, public discussion about disadvantage often lacks sufficient complexity and context.

"There is still a particular tone within reporting, particularly news reporting, that is constantly gauged in the language of disadvantage," Ms Mundine said.

Mr Mokak said Aboriginal Australians continue to be "framed, judged and defined by others" with a main media narrative that revolves around "'the five Ds': disparity, deprivation, disadvantage, dysfunction and difference".

"We're always seen as over-represented on some things like the incarceration rate, or being behind in others like life expectancy and education," he said.

Ms Mundine says the blanket negative coverage can have a disempowering effect.

"If someone constantly tells you [that] you're to die of diabetes and health problems, or that you're ugly, then at some point it's on your own psyche," she said.

"And then you might think, why try? What's the point of coming up against barrier after barrier?"

She added: "If we think back to what was happening in 1916, opinions have definitely changed, perceptions and attitudes have changed, but we definitely can do more and better."

- Published12 February 2018

- Published8 February 2018

- Published13 February 2018