Obituary: Keith Murdoch, the disgraced All Black who disappeared

- Published

The most significant moment of Keith Murdoch's international rugby career was the last.

It was 2 December 1972 in Cardiff, the day he made his 27th appearance for New Zealand's All Blacks against one of the all-time great Wales teams.

All Blacks half-back Sid Going chipped the ball forward close to the touchline.

Four, five, six All Blacks rushed forward, "like a great black blanket" said commentator Bill McLaren.

The ball fell to the 17st (110kg) Murdoch before he launched himself at the try line as three Wales players approached.

The try was awarded, even though the Wales players insisted the ball had not crossed the line. The score: Wales 0, New Zealand 10.

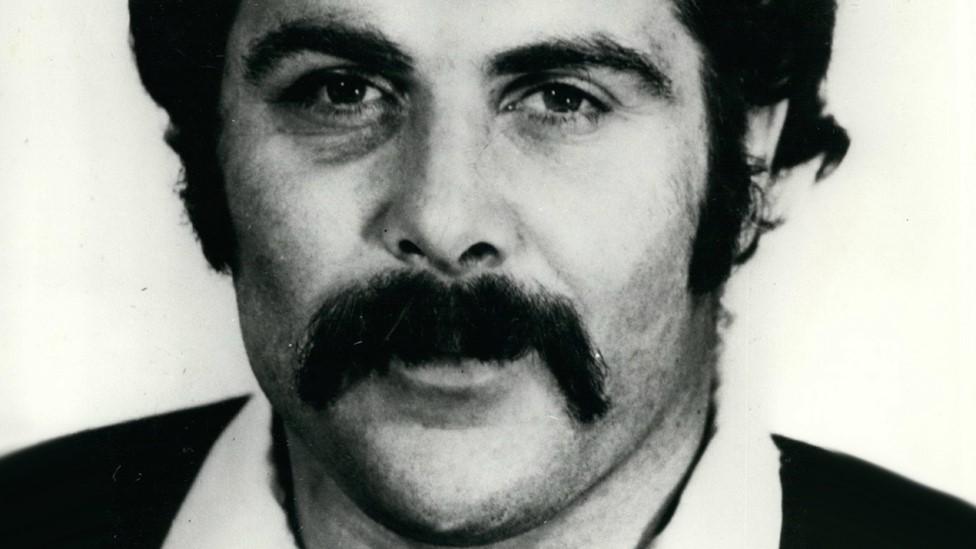

Murdoch emerged from a pile of red and black shirts, handlebar moustache unruffled, with the ball in his hand. There was no expression of joy on the face of the 29-year-old as he jogged away from his team-mates.

The match ended Wales 16, New Zealand 19; Murdoch's try - the only one he scored for his country - had made all the difference.

It would be the last time he'd appear on a rugby field.

It's not clear what exactly happened at the Angel Hotel in central Cardiff a few hours after the match finished but it ended up with a security guard at the hotel, Peter Grant, being punched in the face, and Murdoch being sent home by New Zealand rugby officials a day and a half later.

The players, reports would later say, were upset they had not done more to try and stop him being expelled.

He was the first All Black to be sent home for indiscipline and the move shocked players and fans. "Exit the wild man," the Daily Mail's headline said the day after his departure, "leaving one all-black eye behind."

Different versions of the story exist. Had Murdoch punched Grant after being refused entry to the bar? Had Grant been struck by accident as he tried to stop Murdoch hitting team officials?

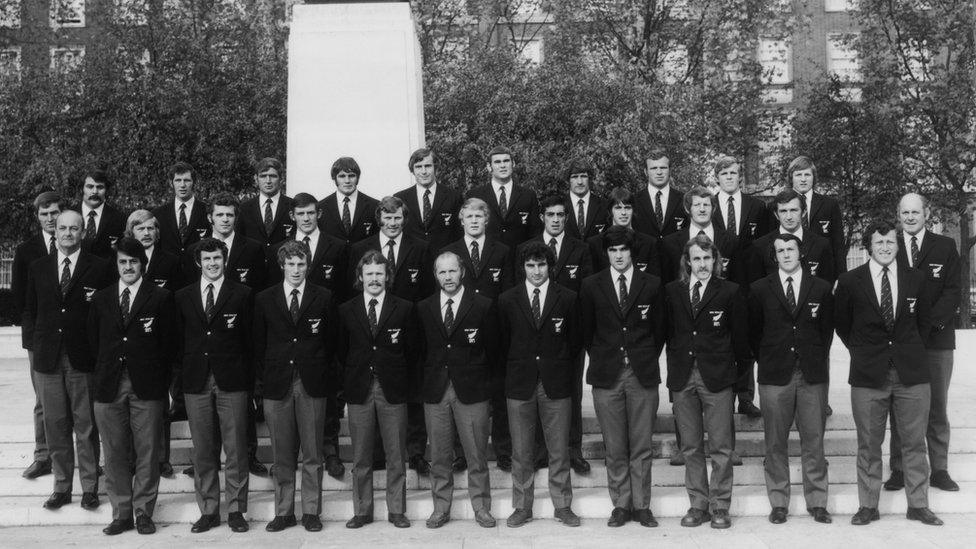

The All Blacks in London in October 1972 - Keith Murdoch is far-left on the top row, with moustache

It was not out of character for Murdoch, whose reputation as a hard drinker able to throw his weight around was already well established. Earlier in the All Blacks' tour, a journalist said Murdoch had assaulted him.

Murdoch's whole job was to stand firm and fight back. As a prop forward, he was the one who would take the full pressure of the scrum on his shoulders, and his size stood out at a time when bulky rugby players were few and far between.

There's also the (true) tale of how he once needed to move a broken-down car away from the road, so he tied a rope around its tow bar and pulled it himself.

But there were also tales of his shyness, his inability to fit in. Murdoch was also seen as "a big, jovial chap with a devilish sense of humour", Ron Palenski, a junior journalist on the 1972 tour, told the BBC.

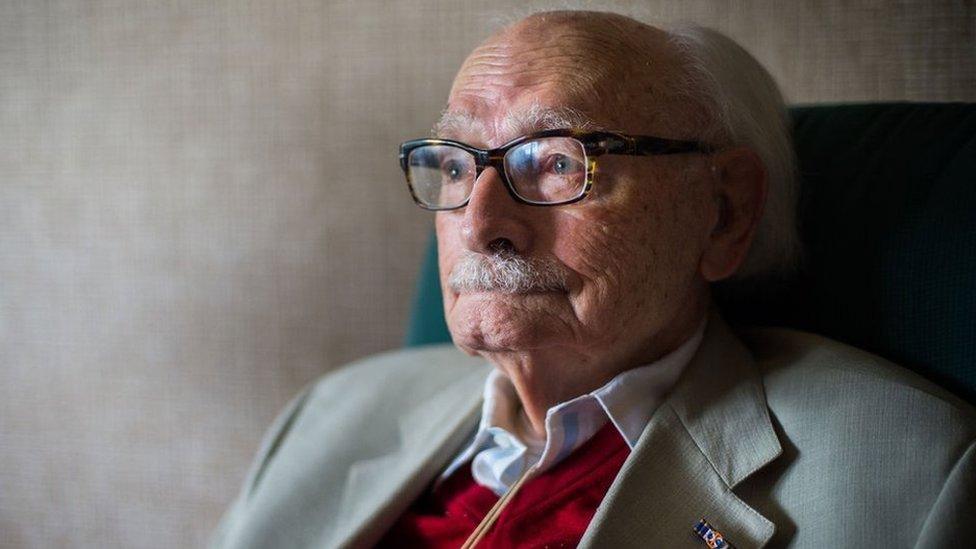

Many more such stories emerged after his death, aged 74, was announced on 30 March.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

The dust-up at the Angel Hotel made headline news in the UK and New Zealand, and the press pack in Auckland camped out at the airport to await Murdoch's return.

He never made it there. It's believed he swapped flights in Singapore, after shaving his moustache to avoid detection, and flew instead to Perth in Western Australia. From there, he retreated to the wilderness of the Outback and disappeared.

Murdoch never explained why he did it, nor why he chose to abandon his rugby career. The lack of satisfactory explanations, and Murdoch's own eagerness to avoid the press, means that many gaps remain in Murdoch's story, gaps that at times have been filled by half-truths and speculation.

There were only four recorded encounters with him in the almost 46 years after he boarded the flight from London.

In the years after Murdoch's disappearance, there had been rumours he had moved to the middle of nowhere in Australia. New Zealand rugby officials had tried to trace him, with no luck.

Then, in 1974, the New Zealand rugby journalist Terry McLean managed to trace him to an oil drilling site near Perth.

Their encounter did not go well.

The first words Murdoch said to him, according to the report McLean produced for The Herald, were: "Just keep moving." Murdoch then turned to McLean's driver and said: "Who brought this so and so up here?"

McLean took the advice and returned to New Zealand. Murdoch, too, kept moving, and he was next seen six years later.

While he was working on a farm owned by friends in Otago, on the southern tip of New Zealand's South Island in 1980, the friends' three-year-old son was found unconscious in their swimming pool.

The boy's mum dragged the boy out of the water and Murdoch immediately gave him mouth-to-mouth resuscitation, saving his life.

Ron Palenski, in his book chronicling the history of New Zealand rugby, said a reporter from the local newspaper the Timaru Herald heard of the rescue and visited the farm to get the whole story.

Murdoch was nowhere to be seen, and shortly afterwards he left for Australia.

Read about other notable lives

In 1990, Margot McRae, a producer for a current affairs programme, received a tip that Murdoch was working for a mining company.

She worked out he was staying at a hotel in Tully, a rainy outpost in far north-east Australia, and turned up unannounced to meet him.

When McRae found Murdoch at the hotel bar, he was shocked. "He was very gentlemanly in an old-fashioned way," she told the BBC. "I was very struck by his honesty - he knew who he was, and what he wanted.

"I was also struck by the fact that he wasn't a tragic figure but had somehow followed the course of what he had always wanted to do."

What he had always wanted, McRae said, was a life without ties - moving from one town to the next, following the work where it was, making friends wherever he landed.

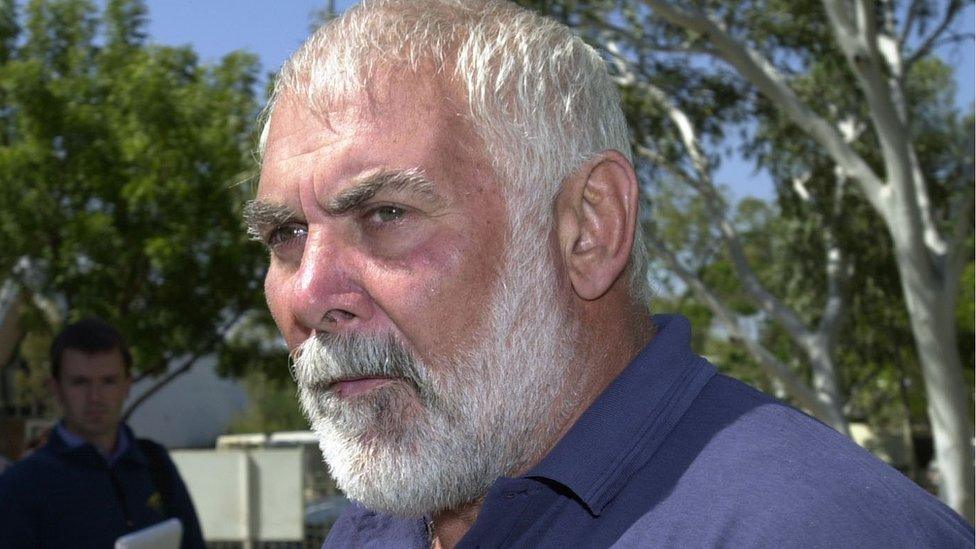

The last public sighting of Keith Murdoch was in 2001, at an inquest in which he played a key part

There was no mystery to the man himself, McRae said, but his story ended up being mythologised by the media and his fellow All Blacks, who traditionally gather at the Angel Hotel to remember him whenever they visit Cardiff. The players call the informal gathering the Murdoch Memorial.

McRae did not get her on-camera interview with Murdoch but he bought her a beer and granted her a quick, polite chat.

A day later, McRae and her crew turned up at a banana plantation where Murdoch was working to try and get footage of him. When McRae called his name, he dropped his equipment and sprinted away into the wild.

McRae acknowledged she had played her part in creating the myth around him, having written a play about their encounter, Finding Murdoch, in 2007.

The play will be staged in Dunedin, where Murdoch was born, from 26 April.

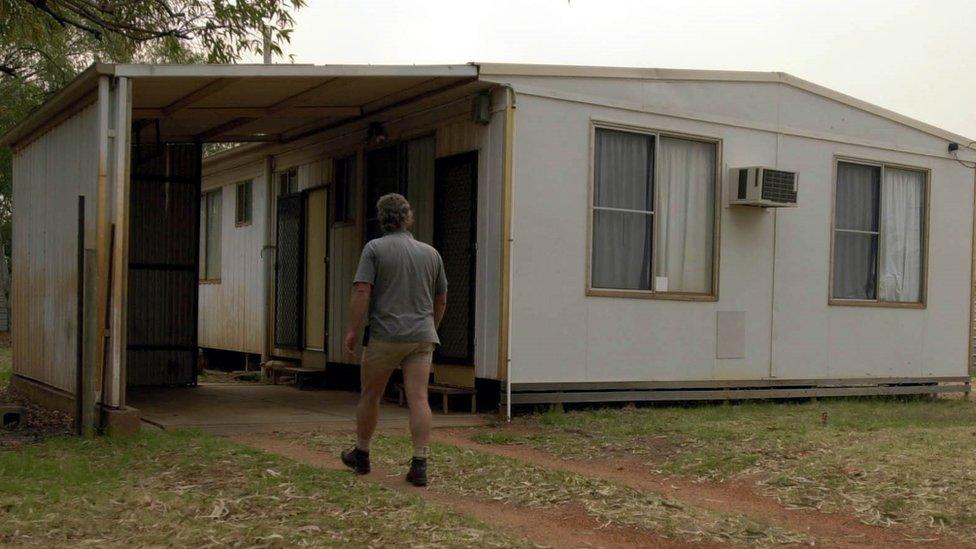

Murdoch passed through the mining town of Tennant Creek, deep in Australia's Northern Territory

In October 2000, Murdoch had been one of the last people to see a young Aboriginal man, Christopher Limerick, alive in Tennant Creek, a tiny gold and copper mining town about 1,000km (600 miles) south of Darwin. Soon after, Limerick's body was found in a disused mine and Murdoch had moved on again.

Limerick had broken into Murdoch's bungalow, which the former All Black shared with two other drinking buddies, in August 2000. Then in October 2000, he did so again and was arrested.

Limerick then disappeared and it later emerged that Murdoch had told a friend: "I don't think he'll come back."

Limerick's body was found two weeks later. Murdoch was nowhere to be found and when the inquest began in July 2001, a call went out for him to appear at the hearing - not as a suspect but a "critical witness".

The bungalow where Keith Murdoch and his friends lived in Tennant Creek

Police eventually tracked Murdoch down to a cattle station hundreds of kilometres away and, with some reluctance, he appeared at the inquest in July 2001. He was missing a few teeth and had a white beard instead of a moustache but was still recognisably the prop forward of old.

In his summary, coroner Greg Cavanagh said, external Murdoch "gave his evidence in a cavalier and disingenuous fashion". Murdoch, he added, "was determined to protect himself and his (unknown) associates from being accused of anything".

And while it was concluded that Limerick had died of exposure, having stumbled into the mine looking for water, the coroner said there was evidence of assault and that Limerick had been taken to the mine against his will.

No charges were ever brought and Murdoch was never directly accused of a crime.

Murdoch, who walked past reporters at the inquest with his thumbs in his ears, moved on again.

He did not appear to have much contact with his few family members, but it was his sister who confirmed the news of his death. No funeral details have been announced. It is believed to be taking place in Australia.

Despite his reclusiveness, Murdoch did remain in contact with the people who mattered to him, including former All Black Lin Colling, who died in 2003. Murdoch would return to New Zealand from time to time, and the friends he visited would help protect his privacy.

While there, Murdoch never did collect the caps he was owed after his international appearances. And he never did turn up for the All Black reunions, where an empty chair was always left in case he chose to appear.

- Published30 March 2018

- Published25 March 2018

- Published18 March 2018