The immigrants who built Australia's 'fairytale' castles

- Published

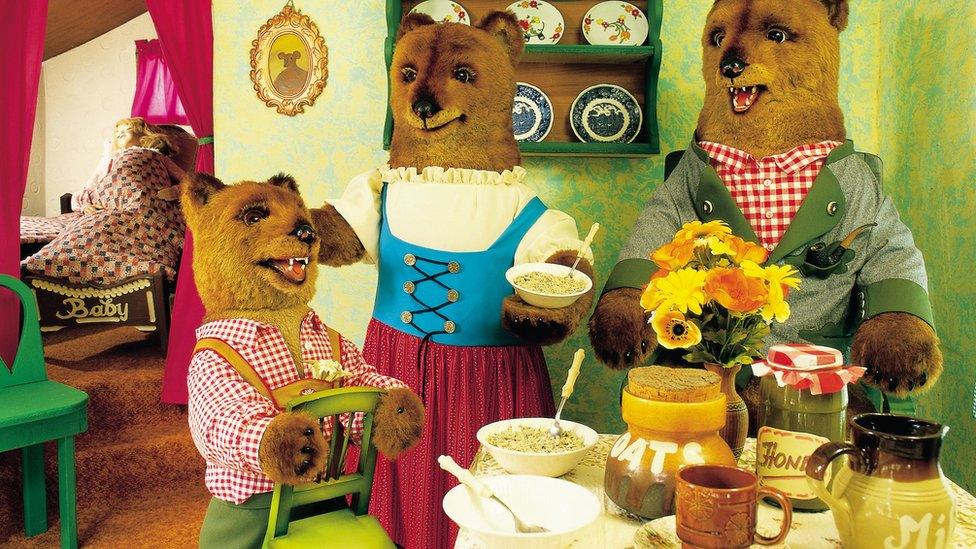

Fairy Park, built in the 1950s by German immigrants, won over initially sceptical locals

In 20th Century Australia, nostalgic European immigrants far from home chose unlikely settings to build shrines to old traditions and in the process created Australia's first theme parks.

When asked what it was like growing up in Australia's first theme park, Garry Mayer says his mind goes straight to the parties. "They were big get-togethers for people who like a bit of wine," he says wryly. "Every weekend."

The Mayers originated from Germany's Black Forest area. It's known as the "fairytale trail", immortalised by the Brothers Grimm. "The tradition at weekends was to walk up the hill to your local rundown castle, and have a cake and a coffee or a wine," Garry explains.

And so it was that, in the late 1950s, nostalgic immigrants in the state of Victoria rolled up their sleeves and mucked in with the building of Fairy Park - when they weren't busy celebrating this new-found social scene, that is.

Peter Mayer had migrated to Australia post-war, along with his wife Elisabeth and 21-year-old son Helmut. The family got jobs near the city of Geelong.

Helmut and Peter Mayer began work on Fairy Park in the 1950s

To supplement their income, they made clay figures of fairytale characters. Now all they needed to abate their homesickness was a castle in which to display the figures.

They started more modestly with a café that had a view of famous local granite peaks, the You Yangs.

Every weekend, the Mayers camped out and cleared trails to create their Grimm kingdom. Peter was an electrician and Helmut a window-dresser, so they combined their skills to canny effect.

"The local perception was that they were the crazy Germans in the bush," says Garry. "They spent all their savings on the park and when it opened they had four shillings left, so their biggest concern was that the first visitors would offer a pound note that they couldn't change."

Upon its opening in 1959, Fairy Park attracted plenty of column inches in magazines and newspapers, and the inclusive attitude of the Mayers won over suspicious locals.

"My grandmother made a lovely cheesecake but the Aussies would never buy them," Garry recalls of family lore. "Then my father came up with the idea of calling it a mooncake - and suddenly everyone started saying how delicious it was."

The family relishes the park's "kitsch value"

By the 1970s, Helmut had taken over and - like his father - he didn't believe on resting on his laurels. He was unstoppable in the 1980s, single-handedly building the fairy castle. Now the park is run by his own sons, Garry and Peter, who take care of administration and maintenance respectively.

There are more than 30 attractions, including Rapunzel's tower, Camelot adventure playground and a model train museum. The entrance itself is through a valley of rather psychedelic-looking mushrooms.

"We like the idea that it's dated and quirky," Garry says. "We don't want to go 'big theme park' and we're happy not to have rides. We actually get more adults visiting than children, even when you include all the school buses. It's got that kitsch value."

When Mark and Judy Evans bought Paronella Park in 1993, sceptical locals gave them two years. Then again, locals had called José Paronella crazy some 80 years earlier, and yet his Spanish castle and pleasure gardens became a wildly popular tourist destination.

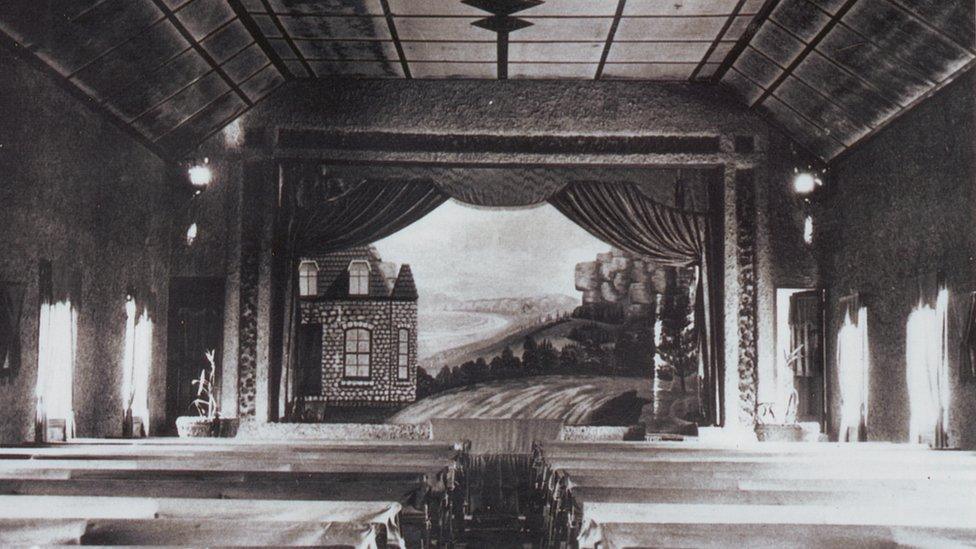

In its heyday, Paronella Park recreated the Roaring Twenties in the Queensland tropics.

Inside its Moorish-inspired walls there was a ballroom, cinema and café, and outside, a tunnel of love, a lovers' lane lined by Kauri trees, tennis courts and fountains.

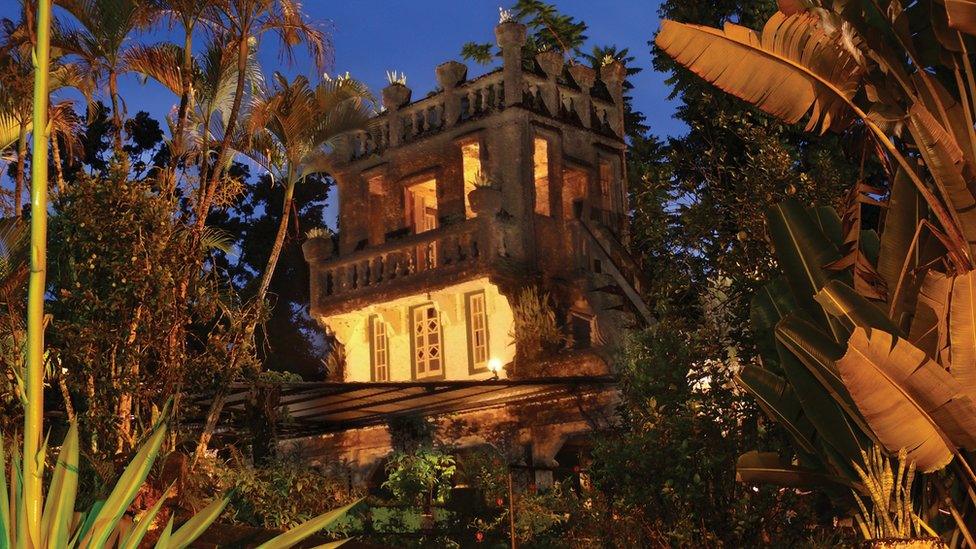

By the time the Evans wandered in, it had acquired a spooky folklore. The castle was matted in moss and half-swallowed up by rainforest. A fire in 1977 had destroyed the ballroom, and cyclones had eroded the landscaped gardens.

Paronella Park is surrounded by rainforest in tropical north Queensland

The mind boggles at how a real estate agent might have described the property to the Evans. A "fixer upper"? A "renovator's delight"?

Having quit their jobs at General Electric, the couple envisioned a move into tourism and were on a caravan trip of Australia to suss out the lay of the land. When someone in Cairns told them about an odd place at Mena Creek, 120km (75 miles) south, they went to take a look.

"It was like walking into another world," Mr Evans recalls. "You could feel it was hiding a story. We simultaneously said: 'Yes, this is the place we have to buy.'"

Mr Evans is a believer in serendipity; it takes a dreamer to preserve the legacy of another man's dream. His predecessor, José Paronella, arrived in Australia from Catalonia in 1913, and worked hard buying and selling sugar cane farms before beginning work on Paronella Park.

Mr Paronella would walk curious locals through the property to explain his plans. Those who chipped in were rewarded with wine and pasta.

The ballroom was used as a theatre in the 1940s

"He wasn't an architect, engineer or a builder by trade," Mr Evans says. "He was a pastry chef." And yet, one of his biggest achievements was building a hydroelectric plant throughout the wet season. The night he finished, he lit up the waterfall to celebrate.

It wasn't just tourists who flocked to the park. During World War Two, Australian troops on R&R paid two shillings for a movie, a meal and a pair of swimmers. (American troops were charged 10 shillings for the same.)

Then, in 1946, a neighbour clearing his land upstream caused a flood of debris that decimated the park. José Paronella died two years later.

Paronella Park fell to further ruin over the decades, but now the Evans have restored the grounds to their former glory.

The park has been damaged by cyclones over the decades

They employ 78 people across the property, a caravan park, a hotel and a rainforest canopy walk. It's won them a swag of tourism awards, but the most meaningful accolade came from Teresa Zerlotti, daughter of José Paronella.

"She took Judy and I for a walk and told us stories from the perspective of being a child," Mark says. "She said it was like stepping back in time."

Jenny Valentish is a freelance writer based in Victoria.