James Ricketson case: 'Dad saved my life so I helped save him from jail'

- Published

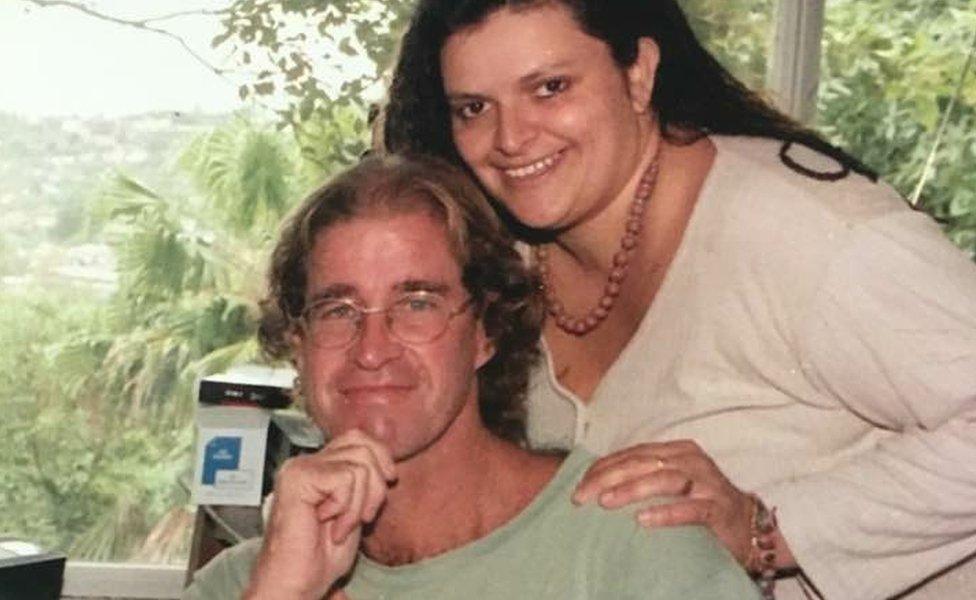

James Ricketson with daughter Roxanne Holmes, after his release from a Cambodian jail

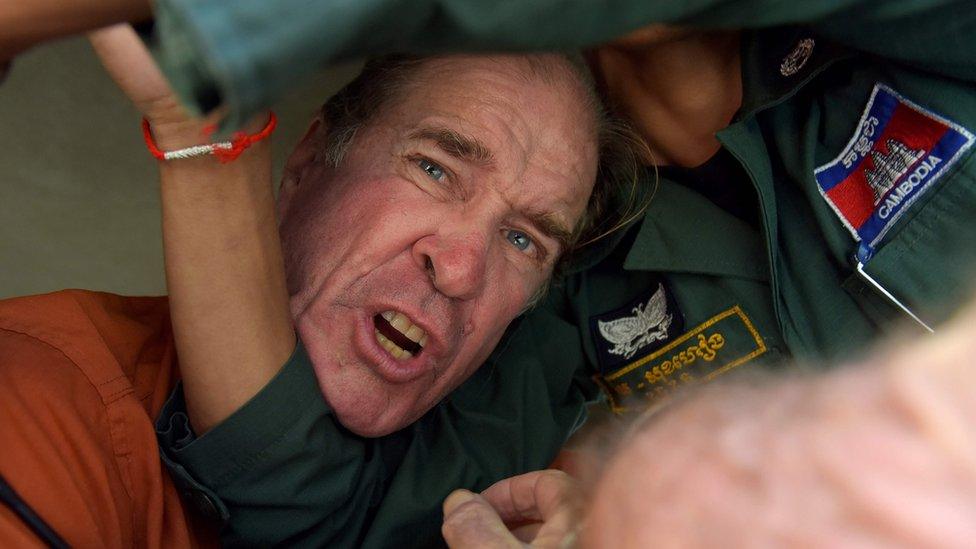

Australian filmmaker James Ricketson was imprisoned in Cambodia in 2016, accused of spying after flying a drone over an opposition rally. His adopted daughter campaigned tirelessly for his release from a cramped, unsanitary prison - until his pardon last month.

But years earlier, it was Mr Ricketson who rescued her from a life of abuse and self-harm. Gary Nunn reports from Sydney.

As James Ricketson, 69, and his adopted daughter Roxanne Holmes, 52, talk to me, their battle scars are showing.

On the arm of Mr Ricketson's shirt sleeve is thick, congealed blood, still seeping through from a fight he had with Cambodian prison guards.

It happened on his final day before his sudden release five days prior to our conversation: "I lost a lot of skin," he says. "But these guards were just doing their job in an evil system. They're not bad guys."

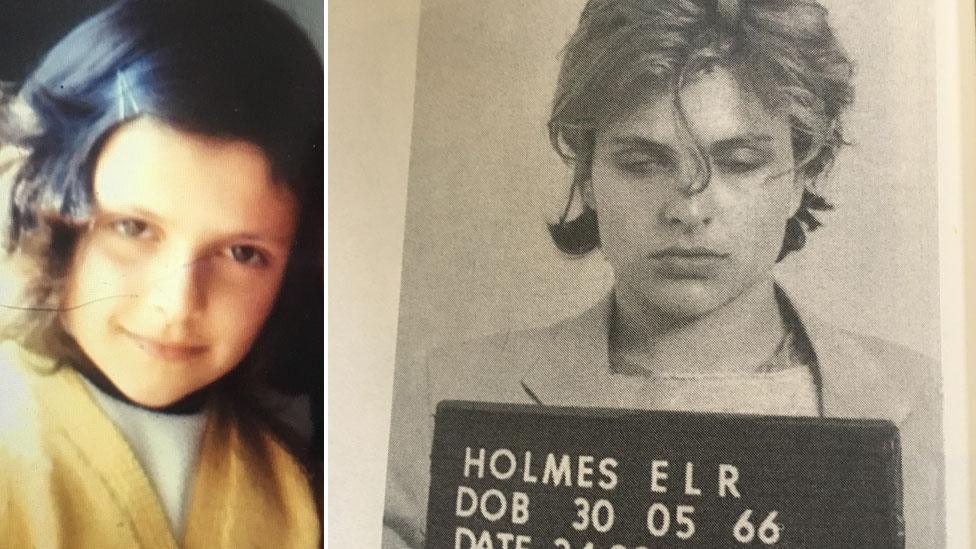

Ms Holmes's arm, meanwhile, shows the indented train track scars of years of self-harm - which she discusses openly - following a childhood of intense sexual, physical and emotional abuse.

Happy at last

But today in Sydney, both father and daughter are smiling. They're enjoying the triumph of Ms Holmes's dogged campaign to release her Australian dad from prison.

This is his first media interview since returning home.

He was being held on a charge of espionage, after flying a drone over an opposition party rally - amid a crackdown by Cambodian Prime Minister Hun Sen on perceived opponents. Mr Ricketson denied the charge, and his trial was called a "ludicrous charade" by Human Rights Watch.

James Ricketson denied charges of espionage in Cambodia

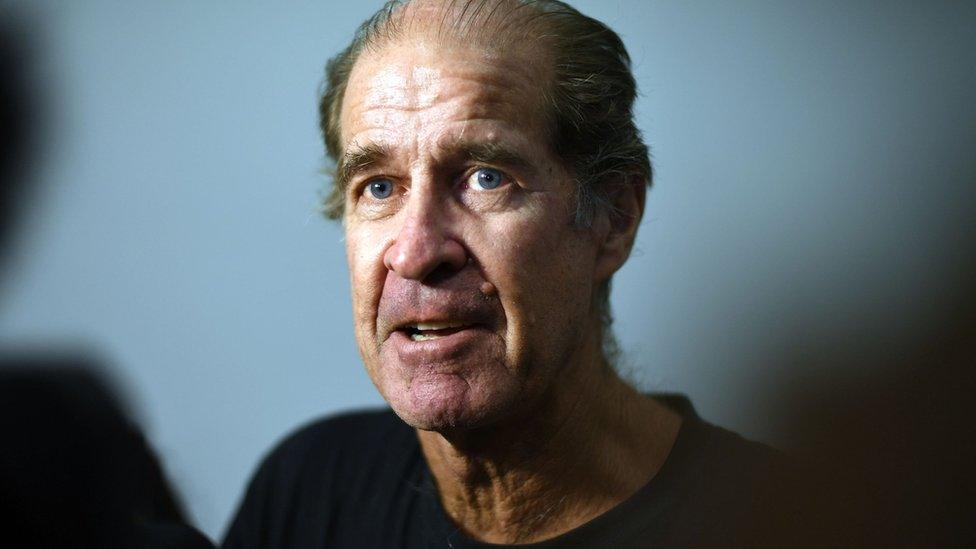

Now Mr Ricketson is re-adjusting to Australian life: "I've only just learnt we have yet another new prime minister," he says. "I've been completely cut off for almost 15 months."

Ms Holmes, meanwhile, shares pictures of him feeding birds. "Seeing his smile with a rosella on his hand has been my happiness," she says.

Campaigning for freedom

By campaigning so tenaciously for Mr Ricketson's release from Phnom Penh's Prey Sar prison, where he shared a vermin-infested cell with 140 others, Ms Holmes may well have saved her father's life; he had bumps to his head, pneumonia symptoms and no access to decent healthcare.

It was so cramped, he had to take it in turns with others to lie down, while lice bites covered him. At one point Ms Holmes shared before and after pictures, external showing he'd lost 20% of his bodyweight.

For her, it was returning a long-held favour.

"I honestly wouldn't be here if it wasn't for James," she says.

"He gave me a voice. When every other adult turned their back on me, James stood by me and made me strong. I used that strength to campaign for his freedom."

"He was always innocent of any crime."

Ms Holmes with Mr Ricketson on his arrival at Sydney Airport last month

Mr Ricketson's trial produced threadbare evidence of espionage, yet he was sentenced to six years in jail on 31 August.

It was devastating for his family, who'd rallied around Ms Holmes's public campaign to free him, using petition platform Change.org.

For Mr Ricketson himself, it required resilience: "Books were my saviour in prison - I'd read 120 of them. Initially I thought, I'll just read 500 books. I knew, with Roxanne's campaign, I could make life a nightmare for both [the] Australian and Cambodian governments."

"I can't deny though," he admits, "there were occasions I thought, I'm just so tired. I'd happily not wake up tomorrow morning - I'm 69, I've had a good life. But my refusal to buckle kept me alive."

In the days after his sentencing, Ms Holmes's petition leapt from 70,000 to 107,000 calling for Mr Ricketson's release.

"He was the first man in my life to show me kindness but now the Australian government has turned their back on him," she shared on the petition in a personal plea to Julie Bishop, then Australia's foreign minister.

Ms Holmes had asked her petition signers to contact MPs. This led former Prime Minister Tony Abbott to call for Mr Ricketson's release, but Ms Bishop didn't respond to Ms Holmes's requests to meet her.

Mr Ricketson at his trial in Phnom Penh in August

When Marise Payne became foreign minister in August, Ms Holmes escalated her campaign by asking all 107,000 signers to call the minister.

A sudden royal pardon occurred on 21 September, which took everyone, including Mr Ricketson, by surprise.

Mr Ricketson became close to "some colourful characters" in his cell, leading to some tearful goodbyes. One man "was eating his own excrement the first time I saw him, and was chained to the wall by his neck".

Mr Ricketson protected him from bullies. "I've a soft spot for people with problems," he says.

'Essentially in jail herself'

This same soft spot saw Mr Ricketson adopt Ms Holmes more than 30 years ago. He met her when researching for a film about troubled young people.

"Roxanne was essentially in jail herself when I met her," Mr Ricketson says. "Something had to break the cycle of her being shifted from one youth detention centre to another."

Ms Holmes aged five, and in a police mugshot when she was 22

A heartfelt handwritten note from Ms Holmes, which Mr Ricketson still has, explains the longing she felt after seeing his relationship with his then five-year old son, Jessie.

The system didn't know what to do with Ms Holmes, as she writes in her published book: "Everyone in the youth justice system agreed they'd never experienced a girl as traumatised, violent or destructive as me."

The book, Roxanne: My Extraordinary Life, details an early life of neglect and abuse, including sexual abuse from her mum's friend. Aged 11, her mum gave her up to be a ward of the state. Then began a life of crime, destruction, addiction and suicide attempts.

In one suicide attempt, she threw herself out of a hospital window and held up medical staff with a garden fork. In another incident, she attempted to burn down a youth detention centre by setting fire to her cell mattress.

Running away with a paedophile, 57, who groomed her, she committed armed robberies across Australia. She often ended up in solitary confinement, which gave her agoraphobia. She writes: "All my life I'd been alienated, segregated, isolated."

Mr Ricketson says his daughter had been at risk of death

She was so troubled, in fact, that in the 1990s, TV show 60 Minutes aired a programme titled The Most Uncontrollable Girl in New South Wales. It reported that staff at a detention centre threatened to strike if she was returned to them.

When Mr Ricketson met her, both the courts and Ms Holmes's youth offender support officer had no "safe place" to send her to. She was a risk to herself and others, with a heavy Valium addiction. Mr Ricketson offered to take her in.

Testing times

The first shock was that she'd told Mr Ricketson she was Roxanne Lee Dargaville, aged 17. In fact, her real name was Elizabeth Lee, she was almost 20 and on the run from police in Western Australia. She recoils today when I say the name Elizabeth; it still triggers her.

Ms Holmes tested Mr Ricketson's love for her consistently; she stole from him and constantly ran away. "Police cars or ambulances were outside my house monthly," he says. "One time I was called and she'd held up a taxi driver. Another time, she tried to steal a police car after being arrested.

"The first thing she'd always ask is: do you still love me?" He said yes every time, even when it became hard. "I knew she had the potential to change," Mr Ricketson says.

"I asked her, why do you keep testing me, even now I've adopted you? She said she was used to chaos; it'd become part of her identity after being abandoned."

The filmmaker says he now wants to help impoverished Cambodian families

As she wrote in her 1996 book, Ms Holmes was so damaged she felt the need to be destructive to compensate for the love she lacked in her childhood.

"I liked it when people hated me," she says. "It was my defence; I couldn't disappoint them." She was later diagnosed with dissociative disorder.

"Many friends said 'just drop her, she's a nightmare,'" Mr Ricketson says. "But you don't abandon your children when you've made that commitment to them. Someone had to help Rox, or she'd die."

Eventually, people in Mr Ricketson's local community asked Ms Holmes to babysit for them. It was then, empowered by their trust, she started to change.

But she was still heavily addicted to Valium. Mr Ricketson was at the birth of her daughter, Arizona, who was floppy for the first few months of her life.

"Mr Ricketson made me realise she was stoned from the Valium through my breast milk," Ms Holmes says. "So he got me off it - and now he's a cherished grandpa to Arizona, and a great-grandpa to her two-year-old daughter Brookie."

The next chapter

The pair have to dart for a doctor's appointment Ms Holmes has made for Mr Ricketson. Before they do, he says: "I'm determined to use my 15 minutes of fame to help impoverished families in Cambodia by releasing them from their economic jail." A foundation is to be set up, called Family by Family.

"That's typical of James," Ms Holmes says. "He's the most humanitarian man you could ever meet."

She's considering writing another book, about her relationship with him. "It'd be called 'the non-spy who loved me'," she says, laughing.

Gary Nunn is a freelance writer based in Sydney.