Aboriginal Australia's 'mind-blowing' struggle for a first treaty

- Published

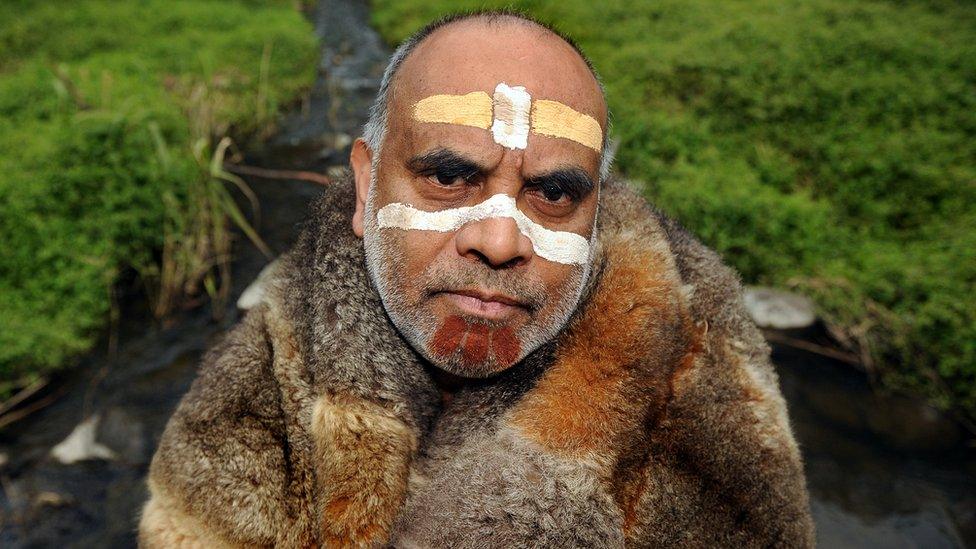

Aboriginal elder Gary Murray says the process carries a risk of "symbolic genocide"

Australia is the only Commonwealth country never to make a treaty with its indigenous peoples. Why has it proven so difficult? Kathy Marks looks at the vast challenges in Victoria alone - a state that is working towards a national first.

Every school holiday, the train would pick up Daria Atkinson and her four siblings, all aged under 10, and transport them - along with thousands of other Aboriginal children from the countryside - to Melbourne, where they would spend up to two months living with a white family.

"We had to call the adults mum and dad," recalls Ms Atkinson, now 56.

"We were told how to sit at the table, how to eat properly. We weren't allowed to get dirty. We had to forget we were Aboriginal. But at least we got to go home - the Stolen Generations didn't."

Having experienced first-hand one of Australia's misguided assimilation programs, Ms Atkinson now works with members of the Stolen Generations in Victoria - people who were permanently separated from their families.

Many of them are still trying to reconnect with their community, culture and traditional country.

The quest has acquired a new urgency as Victoria paves the way for treaty discussions with the state's Aboriginal population - the first Australian jurisdiction to seek a formal agreement with its original inhabitants.

What is a treaty in this context?

A formal agreement that can redefine the relationship between a government and indigenous peoples

For many indigenous Australians, recognition of their sovereignty and right to self-determination is a priority

A treaty can acknowledge and apologise for past wrongs, and establish a "truth-telling" process

It can include compensation for land and resources lost during colonisation

It can set out practical agreements on health, education, jobs and land use

Multiple treaties, with different groups, are a likely outcome

Next year will see the creation of a statutory Aboriginal Representative Body intended to be the voice of indigenous Victoria, which will hammer out ground rules for treaty negotiations in conjunction with the state government.

It has taken nearly three years of sometimes acrimonious consultations and more than $37m Australian dollars (£21m; $27m) of public funds just to get to this point.

Now controversy surrounds the representative body, where - under an official model - 11 of the 28 seats would be reserved for officially acknowledged "language nations" which occupied particular regions before European settlement.

There were, however, 38 such nations before colonisation.

The state of Victoria alone has 38 "language nations"

"So the other 27 will have to fight over the leftovers," says Gary Murray, an Aboriginal elder, referring to the remaining 17 seats, to be decided via an election of all Aboriginal residents. "And that's discriminatory."

Also potentially problematic is that only "traditional owners" - proven descendants of a language nation or clan (extended family) - will be eligible to stand in the election, or participate in eventual treaty talks, or share in benefits flowing from a treaty.

That means that some of the "stolen" people could be, in a significant way, excluded from the treaty process - a process that indigenous Australians have been demanding for decades, and which they hope will deliver them social justice and economic self-sufficiency while helping to heal the wounds of the past.

Meanwhile, there is a more immediate issue: a state election this Saturday, which could lead to the process being junked, if the Labor government of Premier Daniel Andrews loses power.

In South Australia, the conservative Liberal government abandoned treaty negotiations with three Aboriginal nations after winning an election in March.

The Victorian opposition leader, Matthew Guy, is opposed to a state-based treaty, arguing that "a national approach would be a much better way to go".

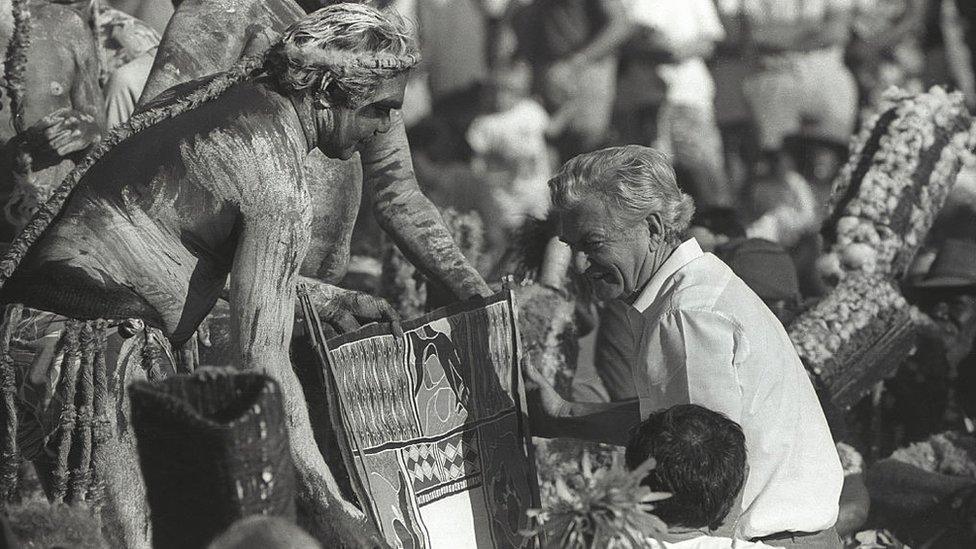

Australia is the only Commonwealth country yet to conclude a treaty with its First Nations, although the subject has been debated on and off for years. Former Prime Minister Bob Hawke promised a treaty in 1988.

Bob Hawke receives the Barunga Statement, a landmark document, in 1988 - prompting his pledge for a treaty

With progress stalled at the federal level, several states and territories have embarked on their own treaty process. First off the block, in February 2016, was Victoria - where Mr Andrews' government has discovered how protracted and tortuous the process can be, even for just one state.

"It's mind-blowing, the amount of work that has gone into this to date," says Janine Coombs, one of the traditional owners on the Aboriginal Treaty Working Group, which advises the Victorian Treaty Advancement Commissioner.

That work has included four state-wide forums, dozens of regional community consultations and "roadshows", a six-day "community assembly" in Melbourne, and legislation enshrining the route to treaty talks, which the government hopes would discourage an incoming Liberal administration from jettisoning the process.

The election for the representative body, to take place across six voting regions, has thrown up multiple challenges. Should, for instance, traditional owners from interstate, now living in Victoria, be able to stand?

What about indigenous Victorians living elsewhere - in some cases just across the Murray River, which forms a boundary with New South Wales?

The man who marched across Australia to call for a treaty

And how will the vexed question of who is eligible to vote - who is, in fact, Aboriginal - be settled?

In Tasmania, in the early 2000s, bitter legal battles were fought over this issue, with the dominant Aboriginal community challenging the right of more than 1,000 people to vote in elections for an Aboriginal statutory authority.

The difficulties involved in setting up a representative body in Victoria - in unifying all the disparate Aboriginal voices - are a legacy of the state's colonial history, which saw indigenous groups pushed off their land and dispersed to distant missions and reserves.

Policies which later created the Stolen Generations severed yet more links with family, community and territory, resulting in a small, fragmented population which today numbers about 50,000.

A crowd watches a historic national apology to the Stolen Generations in 2008

As in other southern states which were swiftly and brutally settled, most Aboriginal Victorians have mixed ancestry.

Model criticised as 'symbolic genocide'

The proposed model for the representative body, Ms Coombs believes, is the "fairest and most inclusive possible", with additional seats to be made available as more language nations complete a formal recognition process.

Mr Murray, though, says that not giving automatic representation to all 38 nations is "offensive, repugnant and symbolic genocide". And he warns that if the model is not amended, he and other vocal opponents will lodge complaints with state and national anti-discrimination authorities.

Treaty negotiations could still be years off, but they promise to be extraordinarily complex, with up to 100 different clan groups seeking separate treaties and, in some cases, disputing each other's territorial boundaries and ancestry.

Nonetheless, some hope the Victorian process could kick-start a momentum that will lead to a federal treaty.

Ms Coombs says: "This isn't a sprint; it's a marathon. The here and now is about setting the foundations and structures right, so that my grandsons and the next seven generations will get the outcomes and benefits.

"Because this opportunity may never come around again."