Christchurch shooting: Australia's moment of hate speech reckoning

- Published

The Christchurch attacks have sparked a debate in Australia about race hate

When it emerged that the suspect behind the Christchurch mosque shootings was an Australian, it set the stage for some agonised soul-searching in his homeland.

The prime suspect for the attack, in which 50 people died, is a self-described white supremacist.

Australia's government immediately joined the unequivocal condemnation of the attack, but the conversation at home was already turning to whether racism and hate speech had become normalised.

The debate turned in Australia

Within hours of the mass shootings, while the rest of the world was still grieving, the debate took an unsavoury turn in Australia when a far-right senator issued a statement in which he blamed the attack on Muslim migration.

Fraser Anning is a senator who entered parliament in 2017 on 19 votes, as replacement for another disqualified lawmaker. He lost affiliation with all parties last year, when he used the phrase "Final Solution" in parliament, while urging a ban on Muslim migration.

On Friday he put out this statement: "The real cause of bloodshed on New Zealand streets today is the immigration program that allowed Muslim fanatics to migrate to New Zealand in the first place".

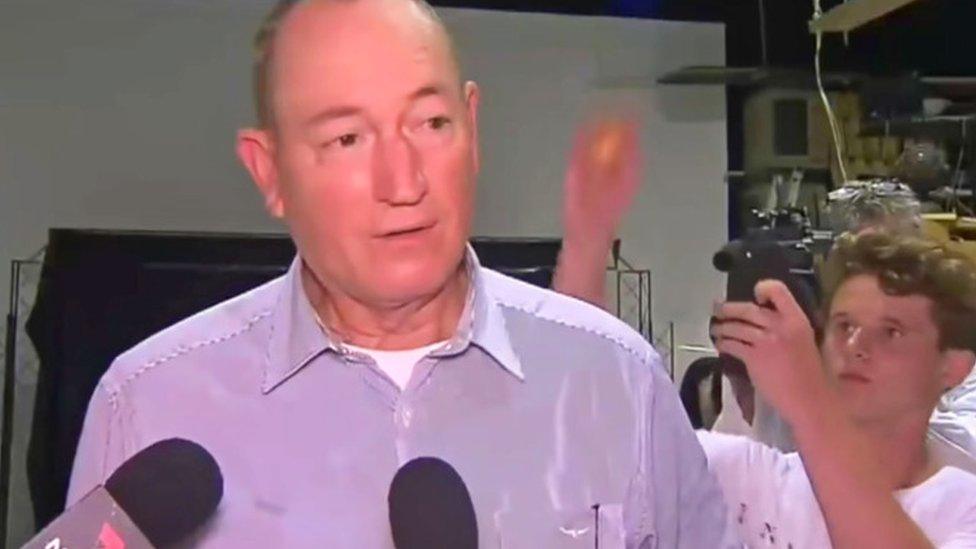

Fraser Anning was "egged" by a teenager the day after his Christchurch comments

The comments sparked immediate fury and condemnation from other lawmakers, who have vowed to formally censure him.

It also prompted overwhelming anger from the Australian public, with close to 1.4 million people signing an online petition, external demanding the senator resign for "supporting right-wing terrorism".

In the day that followed his statement, the debate grew more heated when a teenager smashed an egg on the senator's head at a televised press conference.

The senator lashed out in response, hitting the 17-year-old before his supporters - four adult men - violently tackled the boy to the ground and put him in a chokehold.

The images immediately went viral and "Egg Boy" was celebrated online as a hero, despite criticism from some circles for his actions.

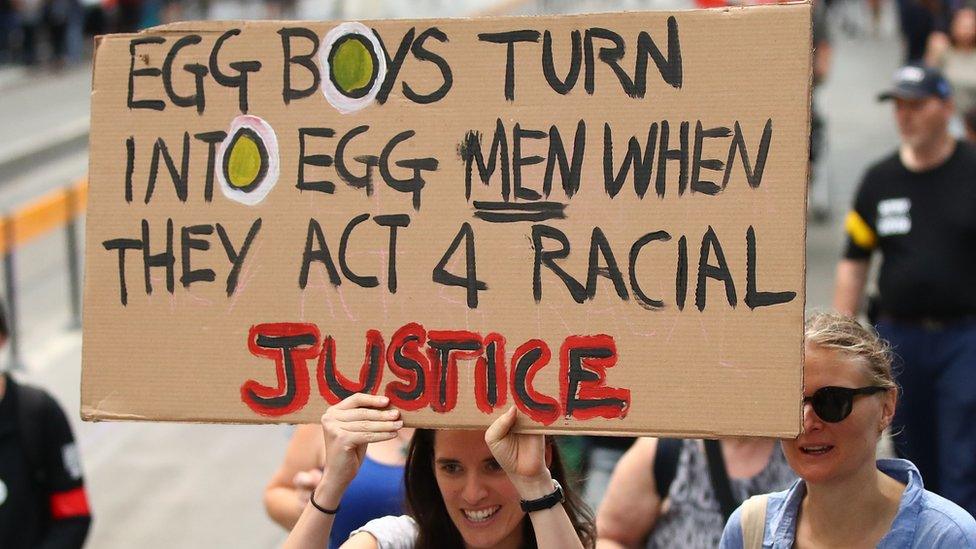

Many Australians praised Egg Boy's retaliation against Fraser Anning

When he was later identified as Melbourne schoolboy Will Connolly, his Instagram account gained 350,000 new followers. He also received more than A$70,000 (£37,000; $50,000) in crowdfunded donations, which he later pledged to the victims of the Christchurch shootings.

The public response was a clear sign of the swelling anger and shame among many Australians and the desire to throw support behind "Egg Boy''s" message.

Outcry, but not surprise

The senator's comments were an extreme example of hate speech but not entirely alien to Australian political debate, says Bilal Rauf from the Australian National Imams Council.

He says rhetoric targeting migrants and minority groups has become commonplace and this has emboldened political violence.

"In many ways, for the people who have borne the brunt of these words, the attack in Christchurch was not a surprise," he told the BBC.

"The situation has gotten so toxic, so fuelled by divisive things that the politicians and media commentators say, that it [an attack against Muslims] was only a matter of time."

Muslim and migrant communities say they have been targeted in public debate

Political journalists have also accused politicians of stoking racial tensions for political gain:

"Australia's hate problem goes well beyond Anning - it goes right to the top", external, wrote The Monthly magazine.

The Australian Financial Reviews newspaper said: "Politicians should know that dog whistling has consequences", external.

Network Ten TV host Waleed Aly also isolated instances of political hate speech, external in a monologue which has attracted more than 12 million views online.

On Wednesday, Mr Morrison was criticised for announcing a cut to the migration intake so soon after the attack, which many feel was fuelled by anti-immigrant rhetoric.

Observers have suggested that Australia's migration debate, while couched in concerns about population control and border security, has also veered into dog-whistle territory in recent times.

So what has been said?

In the past, government ministers have referred to "African gangs" and suggested that Lebanese-Muslim migration in the 1990s was "a mistake".

Australia's former Race Discrimination Commissioner Dr Tim Soutphommasane told the BBC he had seen a "return of race politics" in the past five years.

He notes a "crucial" development was the government's attempts to weaken hate speech laws in 2014 and 2017.

"That encouraged far-right extremists and others to believe that free speech permitted hate speech - that they had a right to be bigots," he said.

Victims of the Christchurch shootings

Fifty people lost their lives in the shootings at two mosques in the city.

There are several other instances. In October, the government backed a motion from far-right, anti-immigration senator Pauline Hanson, which almost succeeded in passing a white supremacist slogan -"It's OK to be white" - through parliament.

The same senator wore a burka into parliament in 2017, in what her critics said was a "political stunt" that risked alienating the nation's Muslim population.

"Some politicians in Australia have for years been whipping up anti-Muslim and anti-immigrant sentiment," said the nation's first female Muslim senator, Mehreen Faruqi this week.

She told the ABC, external: "This is damaging and hurting the community, and this does have consequences."

People of different faith have mourned the Christchurch victims at services across Australia

The government rejected the criticism as political point-scoring. Home Affairs Minister Peter Dutton said Ms Faruqi's comments were "as bad as Fraser Anning's" - sparking further outcry.

Dr Soutphommasane suggests that the Christchurch tragedy should present a "chance for a reset". Australia's political class should now focus on fighting racism and strengthening hate speech laws, he says.

"If leaders here want to counter far-right extremism, they must deal with its causes. For years, we've seen none of that."

What role has the media played?

Australia's media has a long history of peddling racist, anti-migration narratives, says Dr John Budarick, a media researcher from the University of Adelaide.

A comic is asking searching questions about race relations in the wake of the attack

Yet there has been a notable promotion of far-right views in mainstream media following Donald Trump's election in 2016, he says. Analysts say this is a global trend.

"These racist positions are being given public legitimacy. They're being treated as another side to politics and as part of our democracy when they really shouldn't be," he told the BBC.

In Australia last year, far-right activists like Milo Yiannopoulos and Lauren Southern were invited onto mainstream networks for interviews.

Pauline Hanson - who wore the burka in the Senate - had a weekly guest spot on the nation's most popular breakfast show, Channel Seven's Sunrise for years.

Meanwhile, Sky News Australia, a network owned by Rupert Murdoch's News Corporation, last year broadcast an interview with Blair Cottrell, a convicted Nazi sympathiser, which it later apologised for.

Local far-right groups have gained increased media attention

On Friday, it was one of the few broadcasters in the world which repeatedly aired edited clips of the Christchurch gunman's video. It, and other Australian broadcasters Channel Seven and Nine, are now on notice to be investigated by the nation's media watchdog.

It also prompted one of Sky's producers, a 19-year-old Muslim woman, to publicly resign.

"I had many crises of conscience working here, but the events of Friday snapped me out of the endless cycle of justifying my job to myself," wrote Rashna Farrukh in a piece published on Tuesday., external

"I stood on the other side of the studio doors while they slammed every minority group in the country - mine included - increasing polarisation and paranoia among their viewers."

In response, Sky has said it is committed to "debate and discussion which is vital to a healthy democracy".

Many journalists are also pointing the finger at their own industry - although this is a controversial assertion.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

Where to from here?

One of the questions being asked is how some outlets could have loosened their definition of what views are acceptable to allow a platform for.

Dr Burdekin suggests that some are just blatantly partisan and anti-immigration in their views but others struggle under a poorly interpreted duty to editorial balance.

"There's a sense in some outlets that there's a need for balance and that means accommodating extreme views for freedom of speech."

However, he says those on the far-left have not been given the same platform as those on the far-right.

"If we're going to change things, there needs to be a focus now on where we place the margins, on who we give a platform to and who we allow that privilege of having a public voice."

- Published20 March 2019

- Published21 March 2019

- Published31 May 2018

- Published18 March 2019

- Published17 March 2019

- Published1 March 2017