Thalidomide scandal: How Australia's response has 'lagged behind'

- Published

Thalidomide survivor Lisa McManus has been critical of Australia's response

Australia has fallen behind many other countries in its response to one of the world's worst pharmaceutical scandals. That seems likely to change - but time is running out for thalidomide survivors and their parents, reports Gary Nunn in Sydney.

There was a recent six-month period when Trish Jackson, 56, didn't leave her house.

"The minute I step out, I'm laughed at. Stared at. People say horrid things," she says. "Add to that my constant pain - because my feet are my hands, my knees and hips need replacing - and I was in a terrible headspace."

Another factor deterring her from leaving her Brisbane home was that she struggled to get her mobility scooter modified - because she needs to drive it with her feet.

Who is affected?

"Thalidomiders" - a term many survivors use to describe themselves - were born to mothers who took a morning sickness pill which, unbeknown to them, caused birth defects, usually in the form of significantly shortened limbs (in Ms Jackson's case, her arms), or in other cases, no limbs.

It has affected thousands of people globally in a scandal stretching back to the 1950s, when the drug was developed by German firm Chemie Gruenenthal.

But today, Ms Jackson says she is thrilled. A Senate committee report, released late last month, has for the first time recommended government compensation, support and a national apology for thalidomide survivors in Australia.

Trish Jackson took up painting to distract her from "bullying and constant pain"

Lisa McManus, 56, a survivor who has lobbied MPs for the past five years, says, if implemented, these recommendations "will change the lives of Australia's 124 known thalidomide survivors dramatically".

She is "delighted" by the report's findings, though she adds that Australian survivors "have won the battle but not the full war".

Why survivors have been critical

They say that unlike the UK, which made a national apology to its 467 living Thalidomide survivors in 2010, external, and Canada, which recently doubled government compensation to survivors, Australia has never publicly acknowledged wrongdoing, made an apology, or set up a support or compensation scheme.

And unlike in the US, for example, Australia did not conduct a media campaign in the 1960s warning pregnant women, or make efforts to confiscate the drug from homes.

Michael Magazanik, a lawyer and author of a book on the thalidomide scandal, says: "Australia lagged well behind other countries. Although Japan and Canada kept it on shelves longer than others, Australia made a comparatively weak and late effort to get it out of surgeries and pharmacies. It never got it out of homes, and never gave a proper warning."

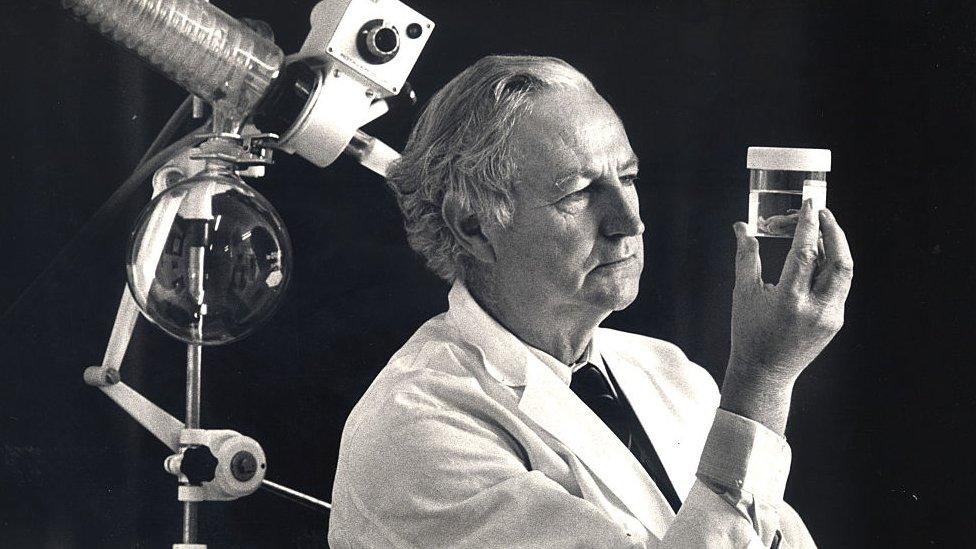

It was an Australian who first warned the world of thalidomide's dangers. In June 1961, Dr William McBride wrote to medical journal The Lancet after noticing deformities.

Dr William McBride first alerted the world to thalidomide's toxicity

The Australian government was warned about thalidomide in December 1961 by the drug's distributor, Distillers. Both Trish Jackson and Lisa McManus were born after that warning.

It's "inexcusable" that this could've been prevented, Ms McManus says: "Of 124 known Australian thalidomide survivors, between 20 and 30 were conceived in that timeframe where the government knew about thalidomide's atrocities, but did nothing."

In 2013, a cohort of Australian survivors won a payout from the company that distributed the drug, but not all were represented in this settlement.

The government has offset tax for survivors who received the corporate compensation, and offered a memorial garden. It has also recently promised to do "what no government has done for the last 50 years and offer a national apology and establish a national memorial", a spokesperson for Health Minister Greg Hunt says.

However, Ms McManus says: "We've been pushing the government for a national apology but as it stands we still haven't received one. We've been offered an apology from the health minister in the memorial garden, but that isn't good enough. We'd like one from the prime minister in parliament."

Wish for parents

Life today for survivors is difficult. Ms McManus says: "There's internal damage, as well as external. Some days the challenge is just getting out of bed. The condition prematurely ages you - we're 25-30 years senior to our chronological age. I have a very active mind - to imagine sitting there unable to act is unbelievably confronting."

The pace of her deterioration scares her: "Two weeks ago I could still sign my name. Today, I can't hold a pen."

Ms McManus was born after the Australian government was warned of potential deformities

Government compensation, Ms McManus says, would help survivors "update wheelchairs and hearing devices, fund home help and modify cars and bathrooms".

Senator Jordan Steele-John, who pushed to establish the Senate committee inquiry, tells the BBC: "The memorial garden offer shows that the Australian government viewed this as a tragedy - not a failure."

A national apology would mean the world to Ms Jackson and Ms McManus, because their mothers, aged 91 and 92 respectively, are still alive.

"I hope [the apology] happens in Mum's lifetime," Ms Jackson says.

"Her guilt is heartbreaking. She needs to hear it wasn't her fault."

Ms Jackson does anti-bullying talks at schools, drawing on her experiences of being "stared at and laughed at"

Ms McManus's mother, who took just two thalidomide pills, "couldn't stop crying" when she heard the Senate recommendations.

"She kept asking: 'Is it really true? They'll look after my girl?'" Ms McManus says.

"That light at the end of the tunnel is no longer the train coming for me. It's hope."