Uluru ban: What do locals think of the final rush to climb?

- Published

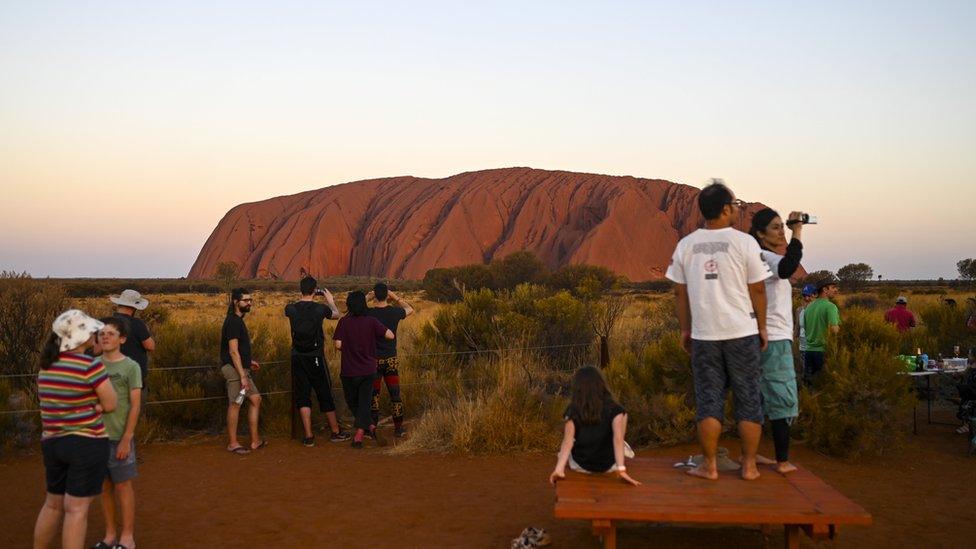

Uluru is one of Australia's most famous landmarks

For decades, hundreds of thousands of visitors to Australia's desert centre have trekked up Uluru, the ancient red monolith formerly known as Ayers Rock.

But from Saturday, the climb will be banned. Uluru is a sacred site for the local indigenous custodians, the Anangu people, who have long asked tourists not to go up.

Most already follow those wishes - only 16% of visitors undertook the climb in 2017, when the ban was announced.

In recent weeks, however, park officials have reported a surge in visitor numbers. Pictures of crowds crammed on to the rock have sparked anger, but also debate about the looming change.

The BBC asked local residents for their thoughts.

'It's our church'

Anangu man Rameth Thomas grew up in Mutijulu, a community very near Uluru. From his home, he can see the 348m (1,140ft) rock - taller than the Eiffel Tower - rising from the desert.

"That place is a very sacred place, that's like our church," he tells the BBC.

Rameth Thomas (fifth from right) with other traditional owners of Uluru

Mr Thomas adds tourists should respect it as a place of lore.

"I've been telling them since I was a little boy: 'We don't want you to climb the rock,'" he says. "All of our stories are on the rock. People right around the world... they just come and climb it. They've got no respect."

To make the ascent, visitors walk past signs at the base of Uluru saying "please don't climb" in several languages. People cite various reasons for continuing on; some say they simply don't give thought to cultural sensitivities, or that the climb is on their bucket list.

"The feeling you get from standing at the top is just indescribable," says one tourist who climbed Uluru recently and doesn't want to be identified. "I felt a sense of reverence for the rock afterwards."

Visitors rush to climb the rock on a morning earlier this month

Mr Thomas urges visitors who feel "they're going to miss out" to consider alternatives such as camel rides, bike tours and cultural activities.

"They could have a much better experience learning about Uluru and the area, and our culture, tradition and religion," he says.

Matt Eccleston runs bus tours to Uluru from Alice Springs, the nearest city 450km (280 miles) away. He says most of his passengers don't climb after learning of Uluru's significance.

Mr Eccleston adds he is most frustrated with some Australian visitors who "are sitting there saying it's 'our rock' - that's the attitude we don't like".

"Everyone's just pushing and shoving each other to get to it first - there's a lack of respect for other people around. It's like every man for themselves at the moment. All us tour guides out here, we can't wait for it to close."

Concerns about safety

Mr Thomas raises another issue about the climb: "It's dangerous, you know? We don't want people dying up there - falling off our church and dying."

Since the 1950s, at least 37 people have died on Uluru due to accidents, dehydration and other health-related events. Last week, a 12-year-old girl was lucky to survive falling more than 20m while descending from the rock.

As custodians of the land, Anangu people feel a spiritual responsibility for the area and those who are there. There is deep sadness when a person dies or is injured on Uluru.

The safety risks of the steep climb come as a surprise to many tourists, according to reviews on travel sites. Visitors have only a metal chain, fixed to 12 iron postings, to help them up - there are no steps or staff stationed along the way.

There are, however, well-marked warnings at the bottom of the climb and strict rules about when it is open. It is closed after 08:00 in summer and whenever temperatures eclipse 36C (96.8F).

Signs at the base of Uluru alert visitors to its dangers and cultural significance

Dan O'Dwyer has previously helped rescued injured climbers on the rock

Dan O'Dwyer worked as a helicopter tour pilot at Uluru from 1998 to 2005. During that time, he was involved in a number of rescues.

"I'm surprised it hasn't been closed sooner," he says. "Not for the cultural reasons, but also for the sheer danger of it. It's a really difficult climb.

"You're not allowed to climb the Sydney Harbour Bridge without a jumpsuit and a harness, and you're hooked on the whole time. I would say the rock is more difficult. It's steeper, smoother, and you're not connected to anything."

This year marks 31 years since Uluru was given back to the indigenous people

One park worker who asked not be named said she feared the Anangu people were being made "scapegoats" for a decision that was unpopular with some visitors.

Another two staff who were not authorised to speak publicly and spoke to the BBC on condition of anonymity said they had seen recent incidents of tourists making racist and aggressive comments over the ban. They questioned whether enough publicity had been given to safety as a reason for ending the climb.

Parks Australia would not specifically address those concerns, but said it had consistently acknowledged the ban was for cultural, safety and environmental reasons.

"The board's vision is that [the park] is a place where Anangu law and culture is kept strong for future generations," a spokeswoman said.

- Published28 June 2018

- Published11 July 2019

- Published1 November 2017