Is Australia really seeing more shark attacks?

- Published

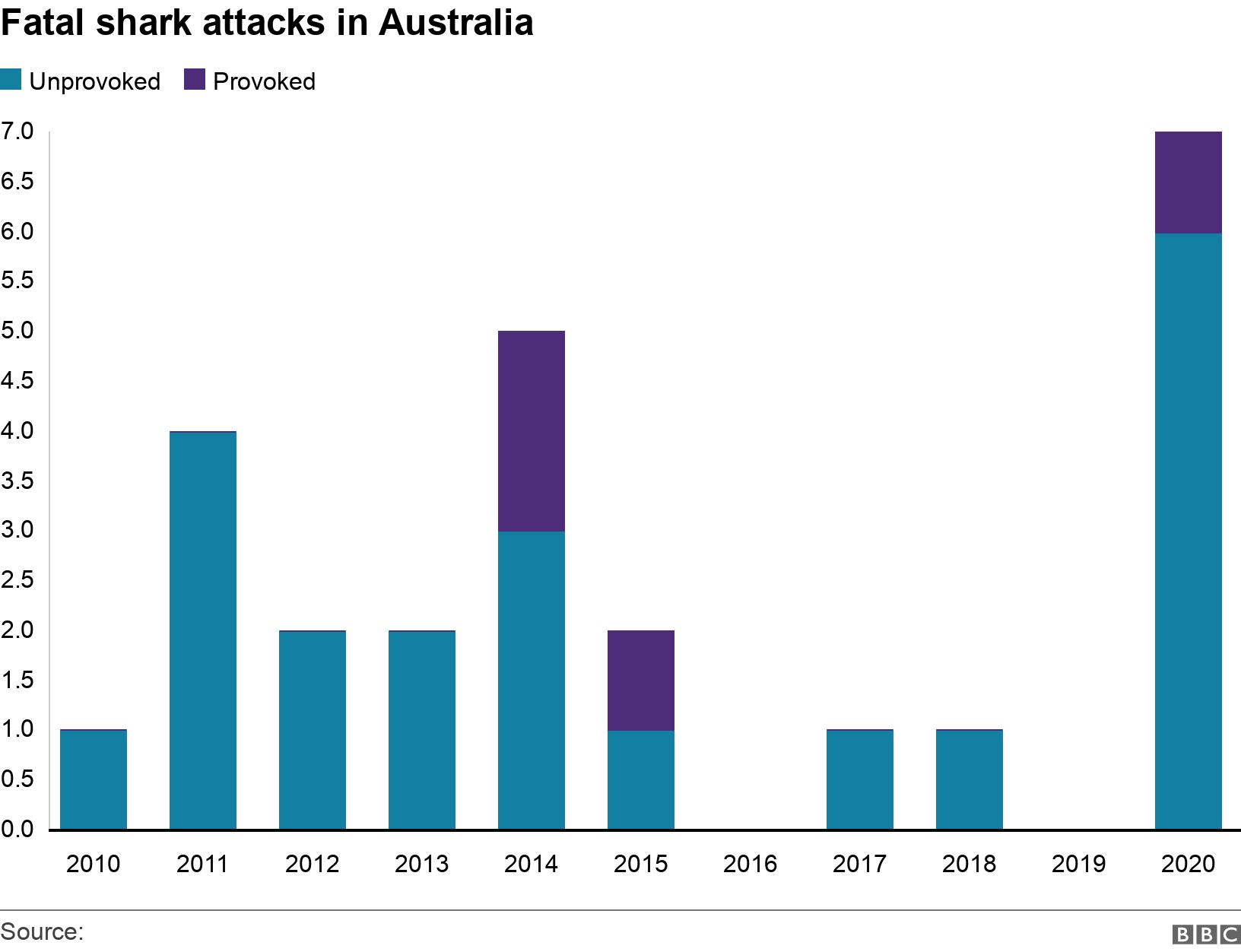

There have been seven fatal shark attacks in Australia this year

The alert about the latest shark attack came last Friday: a surfer was missing; his board dragged from the waves bearing bite marks.

Western Australian authorities have since called off the search for Andrew Sharpe, 52, confirming he was mauled by a shark.

Friends who witnessed the attack said he had been knocked off his board and pulled underwater. Police divers later found scraps of his wetsuit.

His death in Wylie Bay, a popular surf spot, marks the seventh fatal shark attack in Australian waters this year, causing alarm among beach-going communities.

Not since 1929 - when there were nine fatalities - have there been so many.

So is there something in the water, or is 2020 an anomaly?

What do the numbers show?

Looking at the total number of shark attacks reported - fatal and non-fatal - this year doesn't necessarily stand out.

There have been 21 incidents recorded so far this year, according to the Australian Shark Attack File - the official record.

This is just above the average 20 attacks seen per year for the past decade, said curator Dr Phoebe Meagher.

She contrasted this year's numbers with the "noticeable spike" of 2015, when there were 32 attacks - two of which were fatal.

Australia would see warm months (and more beachgoers) for the rest of this year, but "just by looking at the data there's no increase in actual reported attacks", she told the BBC last month.

However, the number of deaths in 2020 is a record in modern times, and the highest since shark nets and other intended deterrents were introduced in the 1930s.

Historically, dying from a shark bite is not common. In over a century of records, the shark attack mortality rate is 0.9 - less than one person per year.

Do we know why deaths are up?

One of the seven deaths this year involved a man who was spearfishing near Fraser Island in Queensland.

This was classified as a "provoked" attack - because the man may have attracted the shark through his fishing activity.

The six other fatal attacks, however, were unprovoked. That's also a record since 1929, though there were four as recently as 2011.

Researchers can't fully explain why unprovoked attacks happen, saying historically low numbers of fatalities have made it difficult to discern causes or trends.

In some cases, witnesses to attacks have reported seeing shoals of fish in the area - something that can attract sharks.

Ultimately, though, much is made of luck and circumstance.

"Whether you get off with just an interaction or a bump or a bite - I think a lot of that will come down to chance," said Nathan Hart, an associate professor of biological sciences at Macquarie University.

This shark tailed a surfer north of Sydney last week - but then peeled away

He noted that most victims were surfers, not swimmers, which meant they were often out in deeper waters and in more inaccessible areas.

Of the four deaths in 2011, two occurred in remote locations. Many of this year's victims have been surfers.

"Sometimes it depends on how many other people are around on the shore, or if you're a very long way from a hospital," Associate Prof Hart said.

"I don't think there's any clear factors which explain the fatalities - and part of that is because it's still a small number we're dealing with."

Could climate and environment be factors?

Last year, Associate Prof Hart and his colleagues studied over a century of shark file data and temperature and rain records.

They concluded that climatic and oceanographic forecasts could help suggest when and where attacks might be more likely to happen.

The team identified potential weather triggers at hotspots like northern New South Wales, where two deaths have happened this year.

In that location the risk apparently peaked when there was significant rainfall. The rain would flush nutrients into the sea, creating a pocket of cooler, turbid water at river mouths and along the coast.

"Such areas of the ocean are highly productive and sharks may be attracted by the abundance of fish or other prey, such as seals, that might follow the fish," Associate Prof Hart explained at the time.

A teenager surfer died in July at Wooli Beach, 630km (390 miles) north of Sydney

He said this was also associated with a stronger East Australian Current, which creates distinct temperature differences in the ocean.

Australia's Bureau of Meteorology has recently declared a La Nina, a weather pattern which typically increases rainfall across the nation's east.

Scientists know that climate change is affecting ocean current movements and weather patterns. Depending on its impact, Associate Prof Hart said, we could in future "potentially see an increase or equally a decrease in shark attacks perhaps in response to those changing environmental variables".

But he stressed that had not been reliably linked to the probability of attacks yet.

"And if water movements change so much that there are more sharks up against the coast, I think we're in bigger trouble than worrying about shark attacks," he added.

What about shark behaviour?

Sharks remain mysterious predators whose behavioural traits are largely unknown.

Associate Prof Hart said they might bite for various reasons, such as lashing out at a threat, protecting territory, or confusing a human with food and "feeling their way" with their mouth.

"Think about a surfer on a board," he said. "To a shark they look like a big, fat seal going through the water, very slowly in many cases."

Do sharks actually want to eat humans? Both he and Dr Meagher suspected that if humans were a desirable food source, many more bites would be reported.

At any point in time, thousands of sharks are in the waters around Australia.

"People regularly go surfing and see sharks and don't get hassled," said Associate Prof Hart. "In fact, a lot of people feel quite privileged to see a great white at the same time as them - scared but privileged."

After fatal attacks, experts have often debated the effectiveness of various shark deterrent measures. We've explored those debates in more detail here., and research is continuing.

But many surfers and swimmers will often say they understand the ocean is a shared environment.

"Unfortunately, that's just the risk that we take when we go into the water," Dr Meagher said.

- Published8 October 2020

- Published9 September 2020

- Published15 August 2020

- Published11 July 2020

- Published19 April 2017