Australia-China row: 'I'm Australian - why do I need to prove my loyalty?'

- Published

Earlier this year, a junior adviser for the Australian government, Andrew Chen*, visited the nation's Department of Defence for a meeting.

As he and a colleague stepped into the building in Canberra, they pulled out their government IDs. Mr Chen was stopped by a guard, who took him aside.

"They asked to take a photo of me - like a portrait - there in the lobby," he said.

"And it was just me. The Caucasian colleague who was with me - he wasn't asked to do that," added Mr Chen, who is Chinese-Australian.

Mr Chen felt "awkward" as they took the snap, but he didn't want to cause a scene. Later, he asked colleagues if they had ever had the same experience - no-one had.

"So it was just me, literally. It was clearly some sort of security procedure the guards were enforcing. They didn't offer any explanation."

The department told the BBC its security protocols were "agnostic of background or ethnicity". Mr Chen suspects that was not true in his case.

He is among many Chinese-Australians who feel they are facing increasing scrutiny and suspicion - solely based on their heritage - as Australia hardens its views towards China.

Accusations of McCarthyism

There are 1.2 million people who have Chinese ancestry in Australia - about 5% of the population.

In October, three of them - all Australian citizens - gave evidence to a Senate inquiry on problems facing migrant communities. But 20 minutes in, each was abruptly asked to "condemn" the Chinese Communist Party (CCP).

When they objected to the question and its relevance, government Senator Eric Abetz pressed them repeatedly, asking "why not?".

Each made clear they didn't support the CCP, but noted that such demands hadn't been issued to other witnesses at the inquiry.

"This felt less like a public inquiry and more like a public witch-hunt," one of the three, university researcher Yun Jiang, tweeted later.

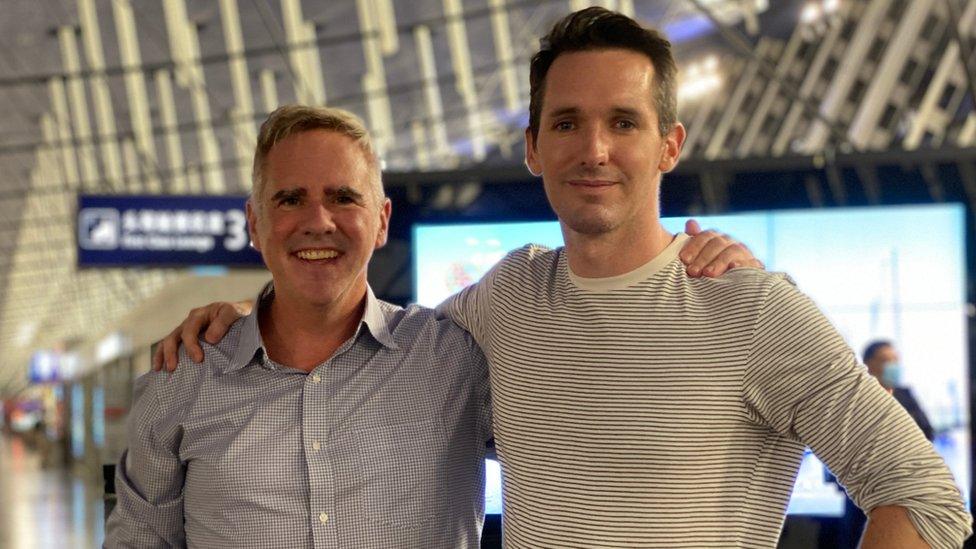

Osmond Chiu compared his experience at the Senate inquiry to McCarthy hearings

Another, Osmond Chiu, likened his experience to those forced to "prove their loyalty" during the McCarthy trials in the 1950s - an infamous purge by the US government against a perceived Communist threat.

"Never did I imagine I would be placed in a similar situation," Mr Chiu, a political researcher, wrote in The Sydney Morning Herald.

He told the BBC: "It was like he [Mr Abetz] was trying to bully us. You kind of think that instead of wanting to hear evidence, he just wanted a political scalp."

Mr Abetz rejected calls by political opponents to apologise. Instead, he issued a statement headlined: "Standing firm against ugly dictatorships is everyone's duty Mr Chiu."

Why are there suspicions?

China is Australia's dominant trading partner, a relationship which has hugely benefited both countries. But in recent years, China has increasingly been viewed by Australia as a security threat.

The Australian Security Intelligence Organisation (Asio) - a spy agency - first warned in 2017 of an increase in China's alleged attempts to interfere in domestic affairs. That same year, a senator resigned over his connections with a Chinese political donor.

In 2018, Australia passed laws aimed at curbing foreign interference. A few months later, citing security risks, it became the first Western nation to ban Chinese firm Huawei from building its 5G network. Australia has also been hit by a series of cyber attacks - often suspected to involve China - on federal parliament, political parties, universities and science agencies.

Negative sentiment towards China has also grown with Beijing's arrests of Australian citizens and its actions in Hong Kong, where it has imposed a draconian and controversial new security law, and Xinjiang, where at least a million people are alleged to have been incarcerated in camps China describes as "re-education" centres. The animosity reached new levels at the end of November when a Chinese official posted a fake image of an Australian soldier murdering an Afghan child.

More on Australia-China tensions:

Also in November, a prominent Chinese-Australian museum board director became the first person to be charged under the foreign interference laws.

But experts say the security dangers are complex and should not be solely focused on Chinese-Australians.

"The greater risks to Australian sovereignty and independent decision-making come not from Chinese-Australian communities, but from people involved in or influencing politics, business and research," said Michael Shoebridge, a security expert at the Australian Strategic Policy Institute (Aspi). "This is where Beijing is focusing attention to silence critics and cultivate advocates."

Yun Jiang has previously spoken about her community research at parliamentary inquiries

But Ms Jiang and others fear that Australia - especially its media - often wrongly conflate the ordinary Chinese-Australian community with alleged nefarious interference by China.

"The focus should be on actions… instead of guilt by association," she told the Senate inquiry.

'Silenced' voices

There are few places where this "guilt by association" is more keenly felt than in Australia's public service, where people work for the national interest, often on sensitive matters.

Many Chinese-Australian bureaucrats say they have increasingly felt under suspicion.

"There are legitimate security concerns [about China]," said one senior policy adviser of Chinese ethnicity, referring to examples such as the cyber attacks.

"But the way it has spilled over into a conversation about the Chinese diaspora and who deserves to be Australian and who is assessed and analysed [for further scrutiny] - it has become a really, really bad conversation."

Younger or less established public servants say they feel pressure to prove their patriotism or are wary when giving policy advice, to avoid unfair scrutiny.

"If I was a Caucasian-Australian, I'd be a lot more comfortable coming out and saying something different," Mr Chen told the BBC.

"But if you're from a Chinese background, people would just see you as being compromised. That's the sort of culture that we've got at the moment."

Several public servants who spoke to the BBC on condition of anonymity - fearing reprisals otherwise - say they have also been questioned by colleagues on past activities that might otherwise be considered an asset. Their examples included learning Chinese at Chinese government-run Confucius Institutes, participating in Chinese youth groups at university, and taking previous trips to China.

They also suspect that security clearances across government are increasingly being delayed for Chinese-Australians, and argue that vetting processes aren't being consistently applied.

"A former colleague of mine joined the public service three years ago - he still hasn't been able to get the clearance," said the senior policy adviser, referring to one process that typically takes six months at most.

Such delays, they argue, have stymied career progression and even prevented people from working for the Australian government. Two people told the BBC they were forced to give up assignments because they never received higher clearance to work on them.

The Department of Defence did not respond to questions specifically about Chinese-Australians, but a spokesman said that security clearances depended on several factors including "the ability to check the background of the clearance subject".

"If an applicant has resided overseas, the evidence provided may need to be corroborated through overseas institutions," he added.

Many Chinese-Australians feel they are facing increasing scrutiny

Mr Shoebridge said the process typically took longer if the public servant had visited "places where it's difficult to get access or reliable information from" - citing China, Russia and North Korea as examples.

He added that the government took extra caution with Australians who have family, friends or other connections in China - because they're seen at risk of being more vulnerable to coercion.

"Chinese state agencies do have a record of using such things to exploit and manipulate people," he said. But, he added, there were also risks in not employing people with experience living in China.

As one bureaucrat told the BBC: "Say you're working in the China policy team. Ideally, you'd want some people from Chinese background in there... but if all the people with in-country knowledge can't get security clearances, then you're left with people that don't have any kind of actual expertise."

'A test of Australia's values'

Jason Yat-Sen Li, a Chinese-Australian community leader, doesn't diminish the risk that people can be targeted and co-opted by China. But he said much could depend on how deeply Chinese-Australians felt part of Australian society - or conversely, if they felt treated like they didn't belong.

The conflict presented a "real test of our values and of our confidence in our institutions", he said.

Asio has long warned against isolating the Chinese community - identifying it as the most helpful group for building national intelligence on China.

Commentators say that the Australian government's silence over comments such as Senator Abetz's did not help.

Australia and China are big trading partners but have disagreed on a number of important political issues

"We need to make sure that the language used by parliamentarians drives cohesion in our community, and doesn't score own goals by advancing the aims of the Chinese government," said Mr Shoebridge.

The underlying issue is trust, said Mr Li. Do Australians trust their Chinese-Australian friends, colleagues, neighbours? And do Chinese-Australians trust in their society, that they will be afforded the same equality and rule of law as everyone else?

"Because if we cannot trust 5% of our population, that is so contrary to liberal democratic values, and that is doing more damage to our democracy than any foreign government," said Mr Li.

*Andrew Chen is a pseudonym.

Related topics

- Published8 September 2020

- Published9 September 2020

- Published8 September 2020

- Published16 September 2019

- Published26 August 2020