How a blow to Australian wine shows tensions with China

- Published

Australian red wine had become a popular drop in China

Imagine, just for a second, the Australian wine industry as a bottle shop. For decades it had loyal customers overseas - old friends from the UK and the US partial to an antipodean drop.

Then a few years ago, a new customer walked in who began eyeing up the reds. Soon, not only were they spending double the other customers, but they were buying the high-end stuff, preferring the premium vintages.

China - this top customer - has bought close to 40% of Australia's wine exports in the past few years.

In 2019, China bought more bottled wine from Australia than it did from France. After an intense few years of marketing and trade deals, this love affair with Australian winegrowers was fizzing along nicely.

Then last week it was corked in the neck. China slapped over 200% tariffs on bottled Australian wine, in a trade hit linked to deteriorating political relations. The one swift blow exposed again Australia's economic dependence on Beijing.

'Buy wine for democracy'

Wine is just the latest Australian export this year to be collateral damage in the wider political battle. Since May, a string of goods - barley, beef, copper, sugar, lobsters, timber, coal - have been halted or otherwise sanctioned by China's Ministry of Commerce.

While Beijing cites trade reasons for the blockages - accusing Australia of illegal dumping practices for its wine - analysts say it's become increasingly clear that the real motivation is political.

That has spurred politicians around the world this week to release a video urging people buy Australian wine "to stand up to China's bullying".

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

The #SolidarityWithAustralia campaign came from the recently formed Inter-Parliamentary Alliance of China - a group of 200 MPs from 19 countries who are known for their hawkish stances on China.

The Australian senator in the video, Kimberley Kitching, argues that China has cancelled Australia's exports because of criticism on human rights.

"This isn't just an attack on Australia. This is an attack on free countries everywhere," she says.

Collateral hit

For local wine-growers, the overnight closure of their biggest and richest market is a devastating blow.

The tariffs at minimum will triple the cost of an Australian bottle for Chinese buyers. What was once a $100 shiraz might now cost at least $300.

"Obviously people aren't rushing out to buy that," said Chester Osborne, a fourth-generation winemaker at the family-owned D'Arenberg Wines in South Australia's McLaren Vale.

Close to a third of his wines were going to China says Mr Osborne

He is a mid-sized producer. The loss of China means a 20-30% cut to sales; staff cuts; and grape and bottle price reductions as product bound for China is returned home likely flooding the market.

For other wine businesses - such as the 800 exporters dedicated almost exclusively to shipping Australian drops over to China - it means almost certain business closure.

At a recent wine-growers meeting, Mr Osborne told the BBC, the talk was all about international politics. Most Australian exporters right now- not just wine-growers - are closely watching the diplomatic play between Canberra and Beijing.

"It's clear as day that that's where we need to be working: how to mend the relationship [with China]," Mr Osborne said.

He contends poor diplomacy on Australia's part has led to these punishments from China.

"The word 'sorry' would be good. I don't think it's going to come out. But saying sorry would be a very, very useful way to change the direction."

China's grievances

Beijing's problems with Australia this year would appear to be articulated in a list circulated by its embassy in Canberra last month.

It listed 14 areas where it said Canberra had aggravated relations. These included a 2018 decision to ban Huawei from its 5G tender, not recognising China's claim in contested South China Sea, and supposed "wanton interference in Hong Kong, Xinjiang and Taiwan".

But foreign policy experts have pointed out that these have been longstanding policies of Australia's. And many - such as criticism of China's harsh new security law in Hong Kong, or the treatment of its Uighur minority - merely reflect its values as a liberal democracy.

"For a long time, Australia complained about human rights issues in China, but the trade was not affected," says Prof James Laurenceson from the Australia -China Relations Institute.

Political tensions began in late 2016, but the two-way trade had continued to grow. "It's only this year the difference in values has been dragged into the trade arena."

So what's changed this year? As China's power has grown in the region, analysts say Beijing is seeing Australia as too openly lining itself up against it.

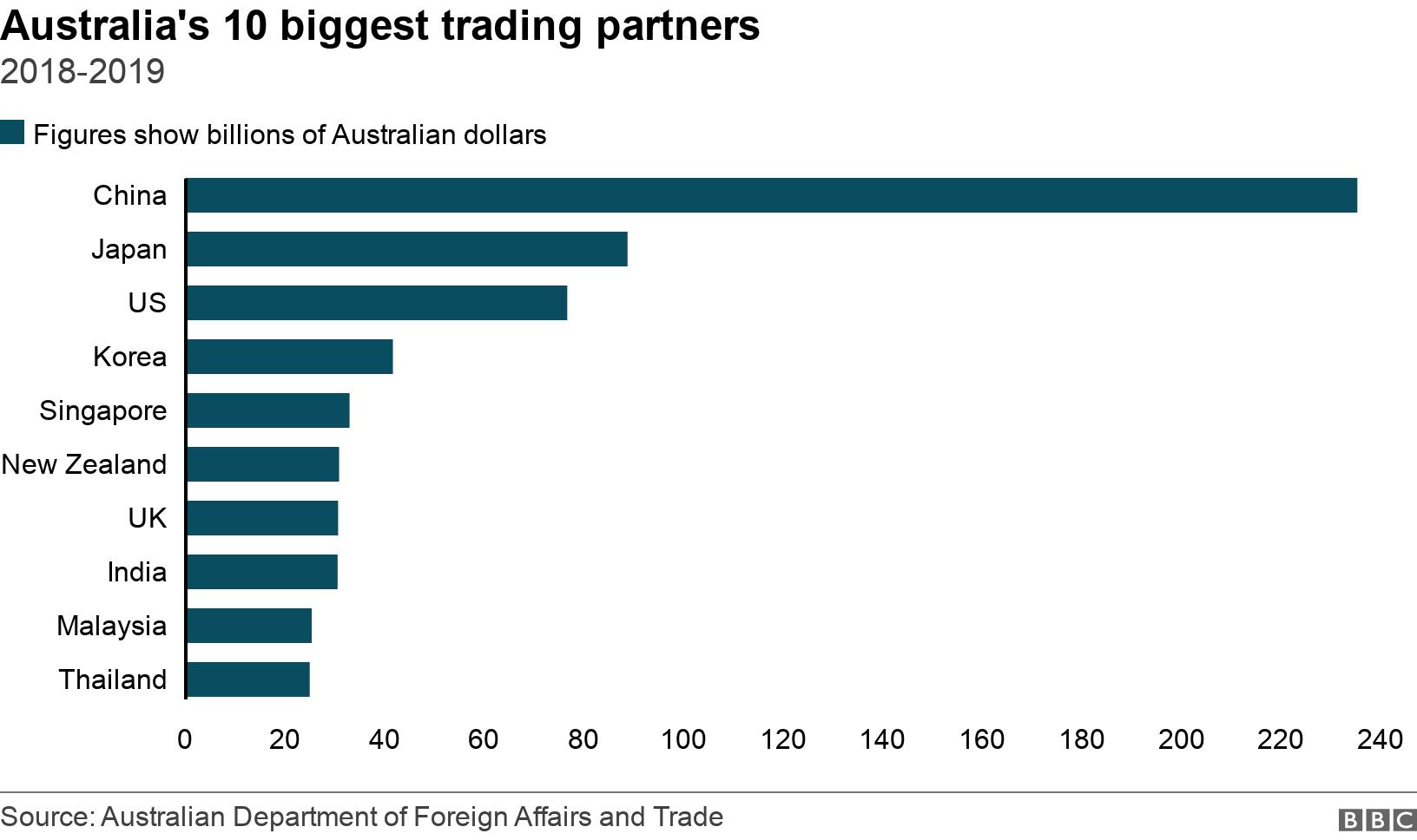

For over a decade, Australia had appeared to straddle a strategic middle ground in the Asia Pacific - benefiting off the region's competing superpowers. It found security in the US-led strategic alliance, while at the same time hitching its economic growth to exports to China.

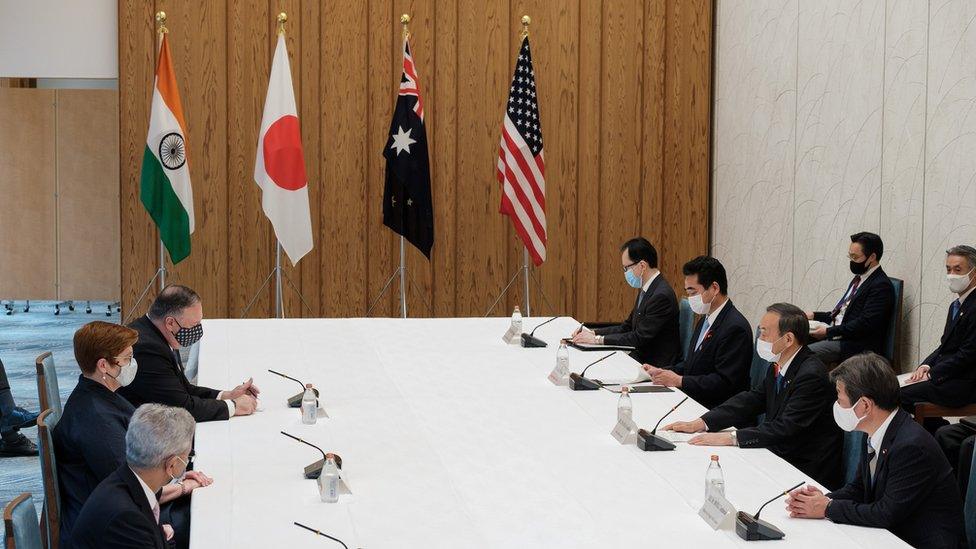

Asia-Pacific allies known as "The Quad": India, Japan, Australia and the US met in October and have strengthened their mutual security commitments this year

But increasingly that neutral middle ground has shrunk. Actions this year - such as Australia's call, echoing US sentiments, for a global inquiry into the coronavirus pandemic focused on China- have angered Beijing. China has also responded sharply to Australia's investigations into alleged CCP interference - claiming national security investigations are fuelled by paranoia and bias.

Beijing has repeatedly accused Australia of being "hostile" and "unfriendly", and targeting it unfairly with its security laws.

"China has fundamentally lost trust that Australia is resisting aligning itself with the United States," says Mr Laurenceson.

"We were dealing with an accumulation of issues but that's the one really fundamental one that has been elevated this year."

Mixed messaging

What has made the situation worse, analysts say, is poor diplomacy that at times has perhaps reflected Australia's uncertainty on where it stands.

On Monday, Prime Minister Scott Morrison launched his strongest criticism yet of Beijing - demanding an apology after a Chinese government official tweeted a fake image portraying an Australian soldier killing a child.

However, in the same statement he appealed to China for a relationship re-set. For two years now, Beijing has declined to answer the calls of Australian ministers in a complete breakdown of top-level diplomacy.

"Despite this terribly offensive post today, I would ask again and call on China to re-engage in that dialogue," Mr Morrison said on Monday. The request was later ignored by Beijing, who defended the tweet.

For wine-growers like Mr Osborne, they're bunking down for the long term and hoping for a decisive, clear line to emerge soon.

"We need to decide what our rhetoric is, and how we move forward as a nation. What battles we want to pick," he said.

"A lot of people in China love Australian wine. I remain hopeful that this isn't going to be something that is permanent."

More on Australia and China:

Why the Australia-China row matters

Related topics

- Published27 November 2020

- Published3 December 2020

- Published1 December 2020

- Published11 October 2020

- Published17 June 2020

- Published8 September 2020