The push to get Australian men and boys to open up

- Published

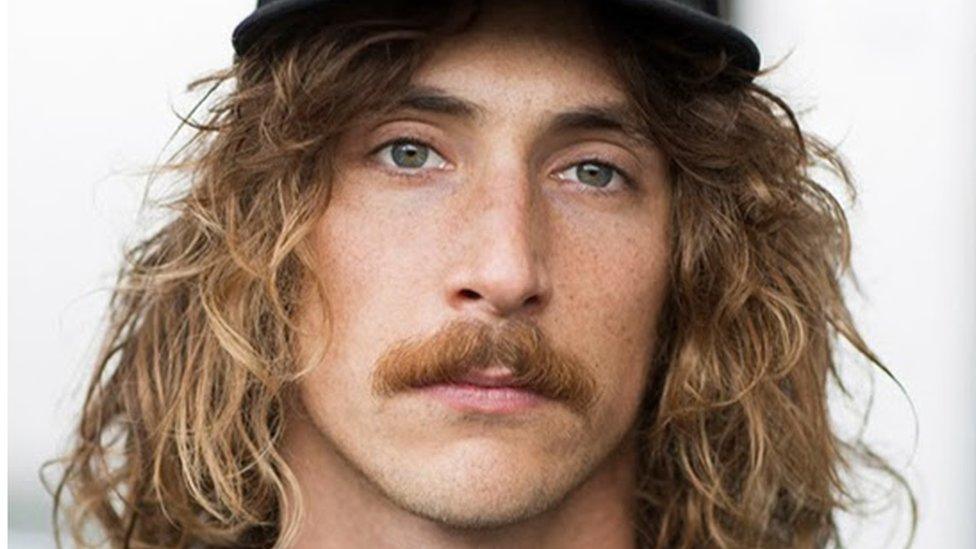

Ryder Jack says it's a "heated time for gender"

Ryder Jack says there are two emotions Australian men can show: happiness and anger. And there's only a couple of reasons to cry.

"You're allowed to cry if you win or lose a grand final, or at a funeral," Mr Jack says.

He runs workshops for men across the country about the state of masculinity in Australia. His organisation, Tomorrow Man, is one of a growing number that seek to help men and boys better understand their emotions and wellbeing.

They aim to improve mental health. Suicide is the leading cause of death for young people in Australia, and men are far more likely than women to take their own life.

Many also hope these programmes will reduce concerning rates of domestic violence in the country.

Our Watch, a violence prevention organisation, says that on average one woman a week is killed by her current or former partner. The stories of abuse are often horrifying: the murder of Hannah Clarke and her three children by her estranged husband, who doused his family in petrol and set them alight shocked the country.

"The suicide rate is horrific, the domestic violence numbers are through the roof. People are waking up to the fact that something needs to change," says Mr Jack.

Outdated ideas

Against this backdrop a movement focused on "healthy masculinities" has gained momentum. Some are run through schools, as well as sporting clubs and community groups.

Those behind the push cite the Man Box research: A study of Australian men aged 18 to 30 that found the majority agreed there are social pressures on them to behave or act a certain way because of their gender.

Sticking to theses rigid stereotypes - like being tough and in control - can be harmful. The study found that men who comply with pressures to be a "real man" had poorer mental health, and were more likely to consider suicide or be violent.

John Wells, a 13-year-old student at Xavier College in Melbourne, did some healthier masculinities training at his school. For him, male stereotypes were tied to traits like physical strength, being good at sport and not showing emotions. But he says those stereotypes are "becoming less and less relevant".

"You don't need to be strong physically to be a man," he says.

Advocates say "healthy masulinities" education should start as early as possible

Tomorrow Man also does work on attitudes. A typical workshop gets participants to put together a "rulebook" of what it means to be a man in Australia. They discuss what works and what doesn't.

What unfolds, Mr Jack says, is a transformative experience for men as they start to open up and share stories about their lives and feelings.

"It's a very heated time for gender. We need to get people into rooms together exploring where they stand at the moment," he says.

More than 60,000 men have been through their programmes. Most of their work is with teenagers.

Harry Reynolds, an 18-year-old cabinet maker from the suburbs of Sydney, took part in a workshop at his football club. He says everyone got a lot out of it.

"It was all about not bottling your emotions. You don't have to be that way, you can tell your mates stuff."

Mr Reynolds says he learnt things about his teammates, like struggles within families or the pressures on a young father.

Tools to cope

Advocates believe developing skills to manage and regulate emotions could lower rates of violence.

Paul Zappa is an educator who has worked in the field for more than 20 years. The former school teacher now works with organisations and children to promote positive behaviours for men to reduce violence, known as primary prevention.

"Domestic violence numbers are through the roof"

He talks about arming boys with emotional intelligence to recognise anger when it rises up, and before it bursts into violence. He says this should be taught as early as possible.

"A lot of kids think, I get angry, I punch a wall. That's just what I do," says Mr Zappa, General Manager of Prevention and Community Development at Jesuit Social Services.

Learning that anger can be handled in another way can be ground-breaking for some adolescents, he says. Instead of punching a wall in frustration, they can begin to spot those feelings and try to release them in other ways.

"When you feel all that, and you know it's coming, walk around the block. The lights go on when [they learn] I can actually change that," Mr Zappa says.

Does it work?

While these programmes may enhance emotional awareness, it is not clear just how effective they will be in reducing violence.

The need is clear. Alongside the alarming rate of women killed by current or ex-partners, Our Watch says 1 in 3 women in Australia has experienced physical violence. Men are overwhelmingly the perpetrators.

Addressing societal and root causes is important. Our Watch say programmes for men and boys that "challenge dominant forms of masculinity" can help prevent violence against women.

In 2020, Australia was shocked when Hannah Clarke and her children were killed by Rowan Baxter

But the group also notes there's a lack of current data that "measures the effectiveness of initiatives which seek to engage men and boys in prevention efforts, particularly in an Australian context", external. More evaluation work need is critical, it says.

Mr Zappa says while the evidence may not be there yet, he's confident these initiatives can produce change. He points to data showing that so-called men's behaviour change programmes - which are undertaken by men who have committed domestic violence - do work.

"Those men have done something in the community that we don't want. And still we can turn them around after the fact. So surely we can do similar things [with primary prevention]."

Mr Zappa says effort and funding rightly focuses on the victims of violence but calls for more attention to be paid to primary prevention.

"They need to double their money… have another pool of money that says, can we stop it before it happens?"

Tomorrow Man will have its workshops evaluated by Monash University this year. Mr Jack also believes their programmes are prompting change.

He says they return to communities and see growth and men being able to express themselves more. The ability to process emotions and improve communication is likely to lead to less violence, he argues.

"The guy that is domestically violent is not some creature from another planet, he's your cousin or your mate, or someone you know.

"But he's not going to talk about that stuff. Men aren't talking about vulnerable things, they use anger, they've gotten away with it for most of their life."

You may also be interested in:

The UN has described the worldwide increase in domestic abuse as a "shadow pandemic"

Related topics

- Published12 June 2020

- Published10 October 2020