Fury as Covid crisis hits Australia's Aboriginal communities

- Published

Monica Kerwin says governments have failed Aboriginal people

"I am angry. The government did nothing to protect us. They sit in their ivory towers and make decisions on Aboriginal issues."

Monica Kerwin is a Barkindji (First Nation) mother-of-six who lives in Wilcannia, in outback New South Wales.

Her remote town of about 750 people is at the centre of a growing Covid outbreak which has brought to the fore how vulnerable Australia's indigenous people are to the virus.

For most of the pandemic, outbreaks in Australia have mainly hit cities and spared remote areas.

But as the Delta variant has spread from Sydney to western New South Wales (NSW) and elsewhere, Aboriginal communities are seeing Covid infections for the first time.

"We're on edge. The [indigenous] population is just not prepared for this pandemic," says Dr Chaitanya Kada, a doctor based in Lightning Ridge, another outback town.

Dr Kada lists some reasons why a significant outbreak in remote Aboriginal-majority communities is a "recipe for disaster":

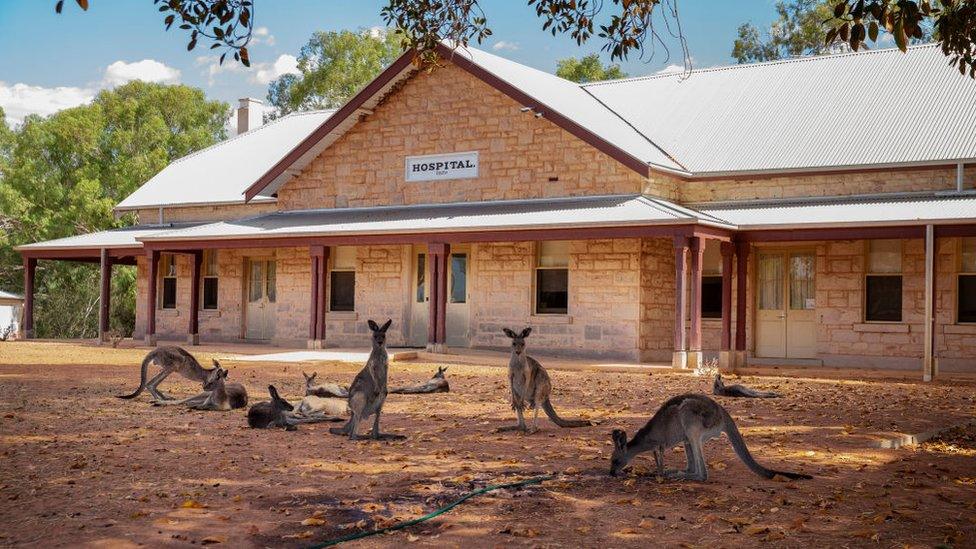

Basic health facilities are not suited to a proper Covid response

There are staffing problems

People have disproportionately high chronic disease rates and a low vaccine uptake

There is often a social make-up that doesn't allow for proper isolation.

Currently, most of the hundreds of people infected in the western NSW outbreak are Aboriginal. Its first death - an Aboriginal man - was confirmed on Monday.

In Wilcannia, more than 60 people have tested positive. Adjusted for population size, that's the highest proportion for anywhere in NSW.

'No one listened to us'

The town's outbreak started at a funeral on 13 August that was attended by more than 100 people, some from other regional areas. It did not breach any public health orders because Wilcannia was not in lockdown at the time.

Nonetheless NSW Health Minister Brad Hazzard described the gathering as "selfish" at a state-wide press conference, provoking anger from the community and the family of the deceased. Mr Hazzard later expressed regret for his comments.

Health authorities remain worried, however, that those mourners could have unintentionally infected people in other communities.

The situation has infuriated locals. Ms Kerwin says she and others had previously asked authorities to seal off Wilcannia to keep it safe.

"We were watching what was happening in other communities. We were watching it [the virus] getting closer," she said.

"We've been crying out for prevention. No one listened to us."

Brendon Adams, who's lived in Wilcannia for 20 years, says there was always a risk of infections arriving in the town because it sits on a major highway.

"The vehicles would stop in Wilcannia and [passengers] would use our public toilets, our takeaways, our one shop or petrol station - which puts our community at risk," he says.

Infections have surged in the remote town of Wilcannia

Vaccination rates are a big concern as they remain disproportionately low among indigenous people.

About 33% of all eligible Australians have been fully vaccinated. Data for indigenous Australians is not as easily available, but The Guardian reported on Saturday it was 16% for Aboriginal people in the region that includes Wilcannia.

"I think it's the fear and mistrust," says Amanda Kelly, an indigenous nurse based in the town of Orange.

She adds that Aboriginal people have a historical mistrust of the government and the health system for past wrongs, and that this has contributed to a slow vaccine uptake.

But Ms Kelly says many remote clinics have also had difficulties getting enough vaccine doses.

Mr Adams, who runs the local radio station, says their broadcasts emphasise the importance of staying home, testing and getting jabs. This includes fighting misinformation around the vaccines.

"My job is to get them the right information so that they can make the choice themselves," he says.

Brendon Adams says the response has been "too late"

But Dr Kada says the government has failed in its messaging to indigenous people, causing confusion with changing advice.

"It should have been consistent and simple. Especially around AstraZeneca," he says.

Poor resources

Ms Kerwin adds that residents feel let down because the government has not understood their needs.

"I am angry because we did not have a [Covid response] plan that was culturally relevant to our community. Their plan catered for suburban Sydney," she says.

"We have people who tested positive staying in tents."

In recent days, most of those who have tested positive have been moved to a caravan park - called Warrawong - on the outskirts of the town.

Mr Adams says that Wilcannia has received more medical support recently, including pop-up clinics for testing and vaccination, with support from the army and police.

But it's "a little too late" that it took an outbreak for that to happen, he adds.

The town has limited health resources

There's growing concern over food shortages for those who can't leave their homes.

Overcrowded households are also a major challenge in controlling the spread of the virus.

"How do we keep ourselves separated with 15 people in one small house who all share a bathroom and kitchen? It's hard and it's painful," Mr Adams says.

"Our people are confused and depressed. But we're coming together as a community to find a solution and get through this."

Last week, after being asked if they had failed Aboriginal communities, NSW Premier Gladys Berejiklian said her government had "worked really hard to support all of our vulnerable communities".

She added that the vaccination rollout was a federal responsibility. Prime Minister Scott Morrison's government has been criticised over its slow rollout to all Australians.

A government spokesperson told the ABC last week that Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Services were among the first to receive vaccines in March.

But the opposition Labor party has accused both state and federal governments of failing to do more for indigenous people, calling for a "national plan".

Living in fear

Ms Kerwin says she's been trying to help Covid-positive parents who have to isolate, buying milk and food for their toddlers.

She adds that some mothers who have been infected are worried about what would happen to their children if they were to be hospitalised.

"For many of us this is a big fear," she says. "Are they going to take my baby away?"

"Many mums have been calling me crying. My heart hurts for them."

Ms Kerwin says she fears things could get worse for her community.

"I worry that it will get out of control. You have families on top of families," she says.

"This shouldn't have reached us."

You may also be interested in:

Indigenous Australian deaths in custody: ‘Why I’m fighting for my uncle’