Who is Anthony Albanese - Australia's re-elected prime minister?

- Published

Anthony Albanese is one of Australia's longest serving MPs and is seeking a second term in the nation's highest office

When Anthony Albanese announced an election would be held on 3 May, he reiterated a promise he made when he became Australia's prime minister three years ago - a mantra he said would define his government.

"No one held back, and no one left behind."

For many, Albanese's ascension to the top job in 2022 had brought a sense of relief - at the demise of his deeply unpopular predecessor Scott Morrison - and hope for a new chapter, free of the political instability and national crises which had plagued successive governments.

Enjoying soaring popularity, Albanese immediately set about upping Australia's emissions reduction efforts, stabilising international relations and implementing key policy changes.

But after three years of global economic pain, tense national debate, and growing government dissatisfaction, Albanese - popularly known as Albo - faced the prospect of becoming the first single-term prime minister in almost a century.

However, on Saturday he managed to pull off an emphatic victory, with his Labor party winning an outright majority.

Who is Anthony Albanese?

Albanese, 61, was raised in social housing by a single mother on a disability pension - as he frequently reminds the public.

Having previously believed his father had died before he was born, he learned as a teenager that his mother had in fact fallen pregnant to a married man, who was likely still alive. Three decades later, he tracked down Carlo Albanese and flew to Italy to meet his father for the first time.

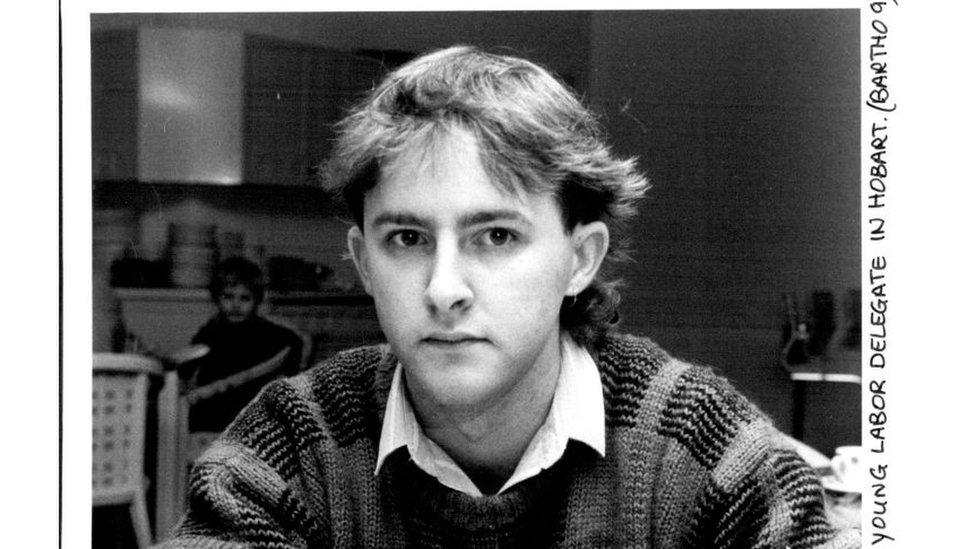

But it was his humble upbringing that Albanese says inspired his career in politics. A Labor Party stalwart since his 20s, Albanese was elected to an inner-city Sydney seat in 1996, on his 33rd birthday.

He is now one of Australia's longest-serving MPs, and is seen by some as a "working-class hero". He has earned a reputation as a defender of Australia's free healthcare system, an advocate for the LGBT community, a passionate rugby league fan, and supports Australia becoming a republic.

Albanese credits his humble beginnings as the foundation for his progressive beliefs

Albanese became a senior minister when Labor swept to power in 2007, and remained an influential figure as the party endured a tumultuous period during which it switched leaders - deposing Prime Minister Kevin Rudd for Julia Gillard - and then switched back again.

A leading voice of the Labor Party's left faction, Albanese has positioned himself more towards the centre since becoming leader in 2019.

He has said creating a better world for his own son, Nathan, is what continues to drive him. He divorced his wife of 19 years in 2019 and plans to marry his fiancé Jodie Haydon later this year.

What is his track-record as prime minister?

Albanese's election to the country's highest office in 2022 ended a decade of rule by the Liberal-National coalition.

He came to power promising to reinvigorate the post-Covid economy, remove Australia from the "naughty corner" of global relations, lower the cost of living, and - critically - hold a referendum on Indigenous rights.

Climate was a key concern for voters and the international community at the time, and the government quickly enshrined into law a stronger emissions reduction target, as well as introduced a quasi-carbon cap for the country's biggest polluters. However, it has continued to approve oil and gas projects, and experts say there is still plenty the government could - and must - do when it comes to tackling climate change.

On China, after years of escalating tensions under the coalition government brought relations between the two countries to historic lows, the Albanese administration stabilised ties with Beijing, negotiating the end of a series of brutal tariffs and securing the first high level meetings in years.

It also reconciled with France, after the previous prime minister blindsided Paris with the cancellation of a multi-billion-dollar submarine contract, and reassured the Pacific that Australia would finally take its climate change concerns seriously.

Many Pacific leaders, like Samoan Prime Minister Afioga Fiamē Naomi Mataʻafa, still want greater climate action from Australia

Economic struggles, however, have beleaguered the government. After a brief bounce back post-pandemic, Australia's economy is growing at its slowest pace since the 1990s, lagging many of its peers, and the country is on the edge of recession amid financial woes worldwide.

Inflation, while it had slowed, pushed up the prices of everyday essentials and left many households struggling with the cost-of-living. The government's relief measures - which include tax cuts, energy rebates and rental assistance - had little impact on the worries of many Australians, for whom this was still the top issue in the election.

Housing is also of particular concern. In recent years, record house prices, underinvestment in social housing, a general shortage of homes and drastically climbing rents, have left much of the nation's growing population struggling to find a place to live. Albanese's first government introduced schemes to help low to moderate income earners own homes or rent more affordably, marginally boosted social housing, and pledged to ensure 1.2 million houses are built within the next five years.

It also curbed immigration and imposed limits on foreign buyers. Labor argued they were making "significant" progress on easing the crisis their government inherited, but critics said they were avoiding bolder, but necessary, reforms that are electorally unpopular with older, wealthier voters.

What has he been criticised for?

Though he has faced far fewer scandals than his predecessor, Scott Morrison, Albanese drew public backlash last year over what members of his own government privately decried as the poorly timed purchase of a multi-million-dollar cliff-top house.

But analysts say the biggest blight on his tenure is The Voice referendum of October 2023, which sought to recognise Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in the constitution, and simultaneously establish a parliamentary advisory body for them.

It was one of Albanese's most defining policies - and his most striking setback. Despite the high levels of support the proposal had enjoyed the year prior, the vote was overwhelmingly rejected after months of often toxic and divisive national debate.

Analysts say the Yes campaign - which Albanese's government did not lead but strongly supported - failed to explain the proposal effectively and struggled to engage voters who would rather the country focus on cost-of-living issues. The opposition - which was against the reform - laid the blame squarely at Albanese's feet, saying he had pursued a costly and divisive referendum that was always bound to fail.

About 60% of Australian's voted No after a bruising debate

The prime minister also found difficulty trying to walk a middle path on the Israel-Gaza war. At first his government loudly supported Israel's right to defend itself. Then, as the number of deaths in Gaza climbed, it supported calls for a permanent ceasefire, urged restraint from Israel, and reiterated its support for recognising Palestinian statehood once Hamas is defeated.

Conservatives accused Albanese of abandoning Israel and blamed his government for a rise in antisemitic attacks in Australia, while protesters have camped outside his office saying he effectively reneged on his previous support of Palestinians.

Ahead of the election, his government pledged a record funding injection into Medicare - Australia's universal healthcare system - which will make it free for most people to see a GP, a promise the coalition immediately matched, as well as small tax cuts and reductions to student debt.

Albanese's approval rating hit its lowest point earlier in 2025, and though it later lifting, polling still predicted a rocky path for him retaining office - a sharp contrast to his mostly positive first year in the job.

Opposition leader Peter Dutton argued Albanese had been distracted with his own agenda, while Australia has gone backwards: "Because of Labor's bad decisions, Australians are doing it tough and they need help," he said.

Albanese, meanwhile, insisted his party had saved Australia from the brunt of tough global conditions, and had the better vision for the country's future.

In the end, Albanese had the last laugh - earning a second term in office, while Dutton lost both the election and his seat.

In his victory speech, Albanese said his party would not take the trust the public had placed in them "for granted" and promised greater social support, as well as working on reconciliation with First Nations peoples.

"Because together we are turning the corner and together we are making our way forward, with no one held back and no one left behind."

You may also be interested in:

Why Australia has compulsory voting