Is Australia still a Covid success - and does it matter to the election?

- Published

How has Australia fared in its battle against Covid?

The pandemic - and PM Scott Morrison's handling of it - was once expected to be a central element of his campaign to be re-elected.

But with the election just a week away, Covid seems to have taken a backseat in Australian politics.

Mr Morrison took credit for saving thousands of lives in his first campaign video - a reminder of 2020 when infections first gripped Europe and the US, but life in much of Australia largely went on as usual.

The country was sealed off from the world, but it began to cautiously open up to itself. "Finally made it all the way to the Sunshine Coast in Queensland," I remember telling my friend.

Australia was hailed as a Covid success story as days went by with zero cases. But as the pandemic has worn on, that theory has been put to test.

The initial success

When the first cases emerged in Australia, Mr Morrison's government reacted quickly with strict measures that controlled its spread.

Every state too adopted fast and firm lockdowns, test and trace protocols, social distancing and mask mandates to contain outbreaks.

The country shut its borders - Australians couldn't leave without official permission and those allowed in had to go through a two-week hotel quarantine.

When the vaccines arrived, the drive picked up after a slow start. Australia is now one of the most vaccinated countries in the world with 95% of its eligible population double-jabbed.

It has also recorded just over 7,000 Covid deaths to date - a small number compared to other developed nations. Last week, the World Health Organization found Australia had recorded fewer deaths in 2020 and 2021 - from Covid or otherwise - than it had in a normal year.

"If you measure success in terms of mortality, there's absolutely no doubt that Australia is one of the success stories among [other places like] New Zealand and Taiwan," says Professor Greg Dore an epidemiologist with the Kirby Institute at UNSW Sydney.

But Australia's harsh border policies and lockdowns came at a huge cost. Tens of thousands of people were locked in or out of the country, separated from their families.

The restrictions, however, couldn't stop the highly transmissible and vicious Delta variant from breaking through in the middle of 2021.

Mr Morrison, who had frequently boasted of Australia's success in controlling the virus' spread, asked people to "hang in there". And when he was criticised for the slow vaccine rollout, he made a now-infamous comment that it "isn't a race".

"It took us too long to [realise] that the zero Covid bubble had burst," Prof Dore said. "The [vaccine] rollout through 2021 was slower than it should've been. It took them [the government] several months to drop the zero Covid public health approach."

By the end of 2021, authorities had decided it was time to live with the virus - restrictions were relaxed and international borders were partially opened to citizens and permanent residents, with the promise of allowing in more international travellers.

From control to crisis

But the Omicron variant brought fresh panic and the government was caught off-guard again.

Australia's case count, which stood at nearly 400,000 cases by the end of 2021, jumped to 2.1 million over the next month.

While deaths have remained relatively low, Australia has already had more than twice as many Covid deaths this year compared to 2020 and 2021 combined.

Australians had swung from one extreme to another. After months of restrictions, they were left to navigate the new reality of living with the virus on their own - and this was while cases soared.

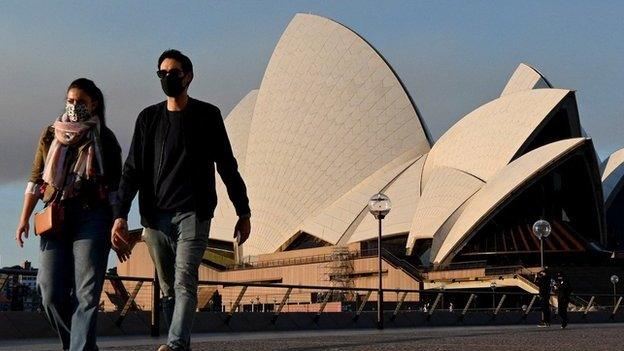

Australia's lockdown separated families for many months

"Every government health agency was informed by modelling that cases and hospitalisations would surge when mitigation measures were relaxed. But there has been inadequate surge planning at all levels of government, leaving us sitting ducks with low third-dose vaccine coverage," Professor Raina MacIntyre, head of the biosecurity programme at the Kirby Institute, UNSW Sydney, wrote back in January, external in an article.

"There was no planning for expedited third-dose boosters, expanded testing capacity, rapid antigen tests, hospital in the home, opening of schools or even guidance for people to protect their household when one person becomes infected."

People queued for hours at overwhelmed PCR testing clinics, only to be turned away in the end. Rapid antigen tests were expensive and not available for a time. Rules about what constituted a "close contact" were confusing and officials flip-flopped on mask and other safety mandates.

As staffing and supply chains suffered, supermarkets emptied out and businesses struggled to survive.

But one of the starkest failures happened in the aged care sector. It was already struggling, but Covid proved devastating, external. Three quarters of the 910 Covid deaths in 2020 were aged care residents, according to a review by Lyn Gilbert, honorary professor at the Faculty of Health and Medical Science in the University of Sydney.

By mid-January 2022, as the country opened and cases soared, the problem in nursing homes became acute with staff shortages. There were more than 7,000 active cases among residents in over 1,000 aged care facilities.

Will Covid matter in this election?

Mr Morrison has at times used the campaign to talk up his economic handling of Covid. And his opponent, Anthony Albanese, used one question in a leader's debate to get the prime minister to concede that his comment - "it's not a race" - was miscalculated.

And yet, Covid has barely been mentioned otherwise.

Australia has double jabbed more than 95% of eligible adults

"It's somewhat surprising given that Australian news coverage for the last few years was dominated by Covid stories and different appraisals of state and federal government's handling of the various aspects of Covid," said Andrea Carson, associate professor of journalism and political science at La Trobe University.

Professor Carson added that data from a sample survey of 100,000 people by the national broadcaster ABC showed that Covid was a long way down the list of issues on voter's minds.

"I think Australians are so tired of hearing about it that they're trying to get back on with their lives," she says.

But it's hard to ignore the full impact of the virus. Sera Dogramaci, a sports scientist and mother of two, has been trying to move forward - "Getting vaccinated and boosted and doing the right thing."

But she said the government had been complacent and unplanned in its response to the pandemic: "I'd give them a five out of 10," she said.

But there is concern of another Covid wave as Australia heads into winter.

"Our health system just couldn't cope. [I've been] talking to friends who are nurses working in hospitals about the number of staff that are burned out and leaving," Ms Dogramaci adds.

"We look to our leadership to lead and for us to know which steps to take. And if they're lazy, things start to spiral out of control."

Related topics

- Published3 September 2021

- Published9 May 2022