Is China really open to improving ties with Australia?

- Published

Australian Foreign Minister Penny Wong and her Chinese counterpart, Wang Yi, met recently

After years of escalating tensions with Australia, China appears to have recently had a sudden change of heart.

"The Chinese side is willing to take the pulse [on bilateral ties], recalibrate, and set sail again," Foreign Minister Wang Yi said last week, according to Reuters.

For more than two years, the Australian government could not get its Chinese counterparts to pick up the phone, let alone agree to a meeting.

But in a possible sign the ice is thawing, the countries' defence ministers met in June, and their foreign ministers met earlier this month on the sidelines of the G20 summit.

How significant is it?

'Words matter'

Australian Foreign Minister Penny Wong hopes the talks are the "first step towards stabilising the relationship".

Relations soured when Australia in 2018 banned Chinese telecommunications giant Huawei from the 5G network, called for an inquiry into the origins of Covid-19 and criticised China's human rights record in Xinjiang and Hong Kong.

China responded by imposing trade barriers on Australian exports - from barley and lobsters to timber and coal - and by cutting off all ministerial contact.

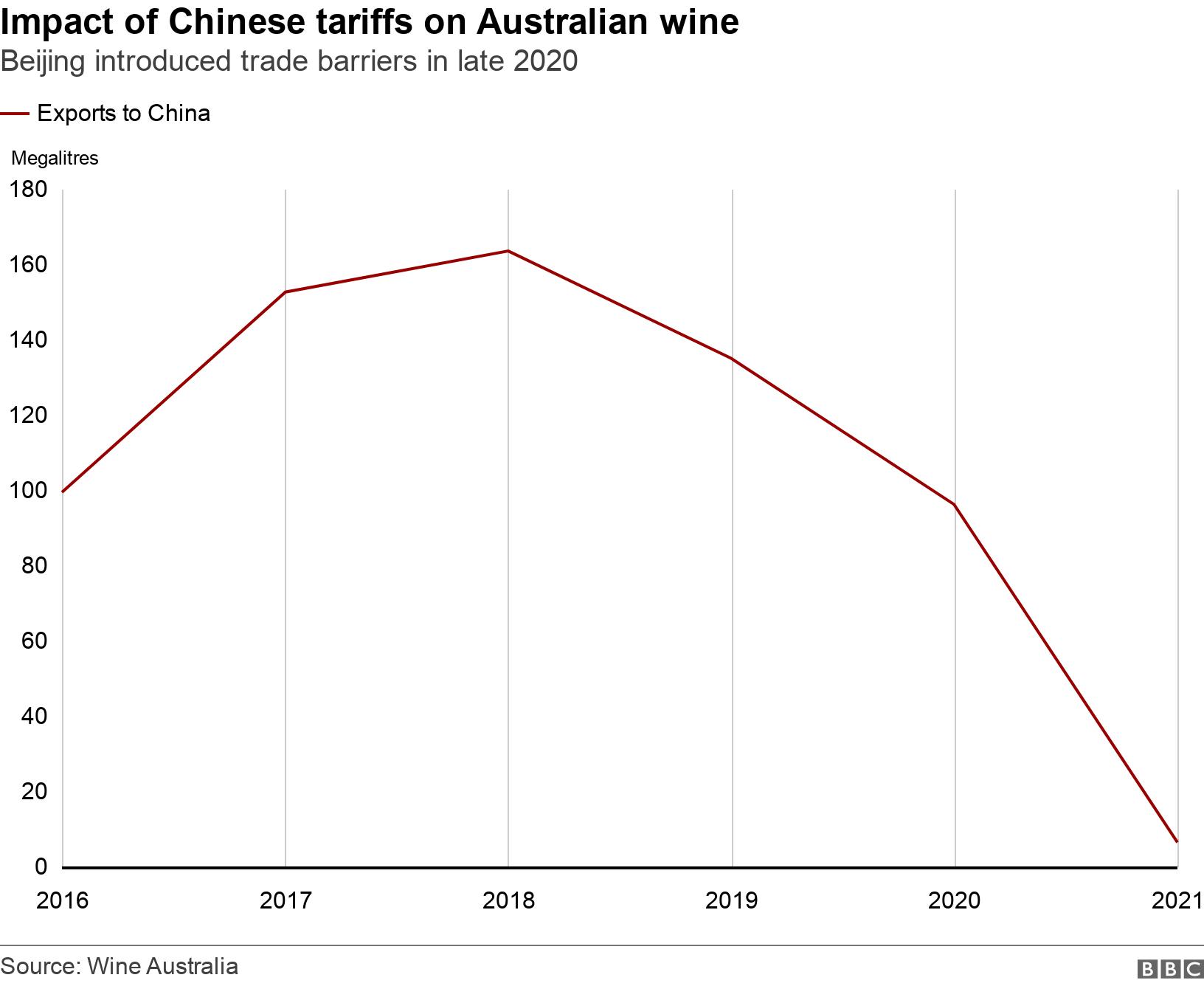

The wine industry was particularly hard hit. China was Australia's most lucrative market - worth a third of all export revenue - before tariffs arrived in 2020.

But since the election of Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese's government in May, there's a been a flurry of bilateral activity and - some say - cause for optimism.

At this point, it's all just rhetoric, says Jennifer Hsu from the Lowy Institute think tank.

"I don't think this is an olive branch… [and] I wouldn't say it's a reset," she tells the BBC. "There haven't been any promises made by either side yet."

But the shift in Australia's tone - away from the "chest beating" of Scott Morrison's government - is still a big deal, she says.

Beijing was critical of that government's comments, including those by then Defence Minister Peter Dutton who compared China to 1930s Germany and said Australia had to "prepare for war".

Mr Wang alluded to that earlier this month, saying the "root cause" of tensions between Canberra and Beijing was "irresponsible words and deeds".

"In Chinese or Asian culture, the idea of face - mianzi - is particularly important," Dr Hsu says.

"Words matter to Beijing. And clearly, its rhetoric and response… really show that it was offended."

In return Beijing has also toned down its inflammatory language a little, but both sides will have to follow up new rhetoric with action, Dr Hsu says.

What does each side want?

Mr Wang says Canberra can do several things to repair relations - in essence, it should treat China "as a partner rather than an opponent".

Some have interpreted his points as demands that Australia stop criticising China, and avoid turning to countries like the US to limit Beijing's influence in places like the Pacific.

China's requests are "unlikely" to have any impact on Australian policy, says Bryce Wakefield, the executive director Australian Institute of International Affairs.

Ms Wong has repeatedly stressed Australia will not make "concessions", saying: "Australia's government has changed but our national interests and our policy settings have not."

On the other hand, Australia's major sticking point is trade. It has accused Beijing of "economic coercion".

"What Australia wants is China to treat it fairly," Dr Wakefield says.

It also wants two Australians separately detained in China freed - journalist Cheng Lei and writer Yang Hengjun.

Spying accusations against Yang Hengjun and Cheng Lei are baseless, their supporters say

It may get some movement on trade, Dr Hsu and Dr Wakefield agree, but other compromises are less likely.

"I can't see China turning around and suddenly allowing the Australian citizens their freedom without compromise from Australia," Dr Wakefield says.

Scope for real change unclear

Given both countries want difficult compromises, will anything actually change?

"I think China recognises it has backed itself into a corner somewhat," Dr Wakefield says.

"[Its] strong rhetoric on Australia hasn't had any effect on Australian foreign policy... and the Australian economy has been fairly well insulated from the effective trade sanctions that China has imposed."

But if China is trying to send a message to smaller powers like Australia that it isn't to be messed with, Beijing is unlikely to back down, he says.

Dr Hsu is more convinced China does need Australia - now especially.

"It's not that Australia is particularly powerful in terms of military might… but it is one potential source of energy security for the upcoming winter," she says.

Last year China suffered power shortages that left millions without heating and the government will be looking to avoid the upset that repeat blackouts could bring.

With the war in Ukraine restricting energy supply even further, it could turn to Australia - a leading coal exporter.

China wants to find alternatives to coal but it remains a cheap and convenient option for many there

But though warmer words have been exchanged, other challenges have intensified.

Last month, Australia accused a Chinese fighter jet of carrying out a dangerous manoeuvre near one of its aircraft over the South China Sea.

And shortly afterwards, an Australian warship charting a course through the same international waters - which are claimed by China as its territory - was stalked by a nuclear-powered submarine, a warship and multiple aircraft, the Australian Broadcasting Corporation reported.

The encounters are a warning, says Dr Hsu.

"[Beijing] is wanting to indicate that it is a force, it is a military power… and that there's definitely a limit to their goodwill."

Related topics

- Published5 June 2022

- Published2 June 2022

- Published31 March 2022