Pride jersey controversy - a reckoning for Australian sport?

- Published

Rainbow detailing on jerseys has led to a massive row in the NRL

Thursday night was supposed to be a proud moment in Australian sporting history.

For the first time, a team in the National Rugby League (NRL) would take to the field in a rainbow-detailed jersey, celebrating inclusion - particularly of LGBTQ people.

Instead, the Manly Warringah Sea Eagles were forced to apologise after seven players decided to boycott the key match on "religious and cultural" grounds.

"Instead of enhancing tolerance and acceptance, we may have hindered this," their coach Des Hasler said earlier this week.

Amid a huge backlash, the players were told not to attend the game for security reasons.

Former club great Ian Roberts - the first male professional athlete to come out as gay during their career - said he was "heartbroken" at the players' decision. NRL Women's star Karina Brown said their boycott had left her "enraged" and "frustrated".

It would discourage other players from coming out, said Josh Cavallo, the only out player in top-tier men's football [soccer] globally.

But others - including some church leaders, fans and players - defended the boycott.

"Each to their own… if we're asked to respect the pride community then we should also respect the Christian or religious community as well," said New Zealand Warriors player Shaun Johnson.

A toxic culture?

The seven players - Josh Aloiai, Jason Saab, Christian Tuipulotu, Josh Schuster, Haumole Olakau'atu, Tolu Koula and Toafofoa Sipley - are not the first Australian athletes to object to wearing a rainbow jersey.

Last year, Australian Football League (AFL) Women's player Haneen Zreika missed a game for the same reason.

But there have been many controversies around inclusion. Most famously, star player Israel Folau was in 2019 sacked by Rugby Australia for saying "hell awaits" gay people on social media.

A few years earlier, a 19-year-old NRL player used an extremely profane and homophobic insult on an opponent. He was banned for two games.

And in 2020, AFL Women's player Tayla Harris was subjected to so much social media abuse - much of it sexist and homophobic - that she offered to give up her salary for the competition to hire an online moderator.

Tayla Harris received a torrent of abuse after a now iconic match photo of her was posted online

Since then an A-League football club has been fined after crowds hurled abuse at Josh Cavallo, and transgender women have found themselves at the centre of debates about who should be able to compete in sport.

All of this conspires to make Australian sport a largely unwelcoming place for LGBTQ people and especially children, an expert in behavioural science tells the BBC.

"Sport is so toxic right now," says Erik Denison, who has spent years researching inclusion in sport in Australia and overseas.

His research on Australia, peer reviewed and published over the last two years, has found:

Just 1% of players in traditional male sport, like rugby, AFL or league, identify as gay or bisexual

About 36% of girls playing in youth teams report being a victim of homophobic abuse, and more than half of boys - those who have come out are the most likely targets.

Over half of men in male-dominated sports say they have used homophobic language in the past two weeks

And homophobic attitudes in sport can have very real effects, Mr Roberts stressed, when reflecting on the jersey debate.

"This is very personal to me, as an older gay person, because I've lost friends to suicide and the consequences of what homophobia, transphobia and all the phobias can do to people."

Is Australia really that bad?

Homophobia in sport is a global problem but Australia seems particularly reluctant to address it, Dr Denison says.

"The fact that it's taken so long and is so hard to get Australia to adopt these things, that in itself is indicative of a serious problem, a lack of care… and a lack of honesty about themselves."

Pride initiatives have been happening for a decade in the UK and longer in the US and Canada. So why are they less common in Australia?

The AFL has a pride round. But Dr Denison said it remains the only major professional men's sport globally never to have had an openly gay or bisexual player, even after retirement.

Mr Roberts says he's long pushed the NRL to introduce a pride round, but suspects fear of backlash from religious players and fans is preventing movement.

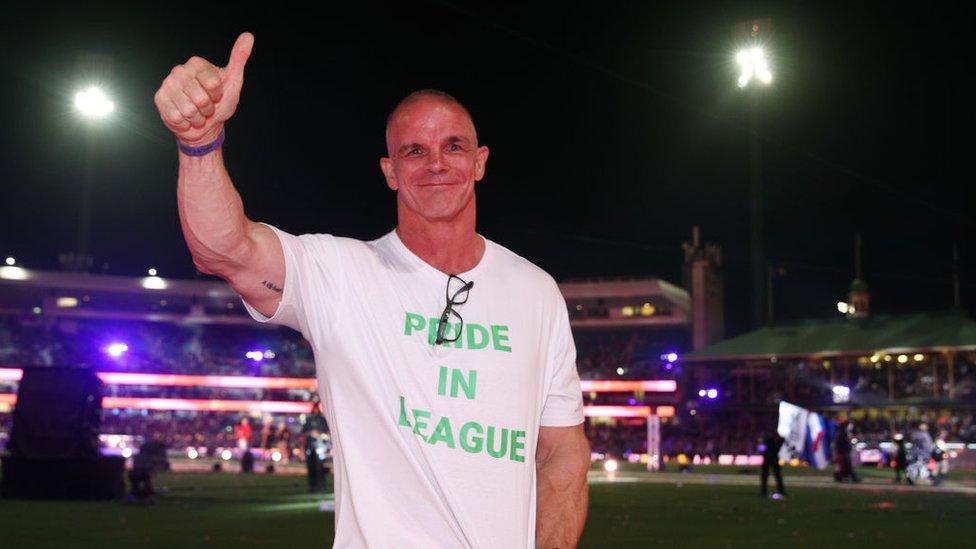

Ian Roberts was the first - and so far only - male NRL player to come out as gay

But Dr Denison thinks the problem is a lack of will and a lack of planning.

"America is the most evangelical Christian country in the world… and we've never had a situation like this.

"[But] you have to have a bit of a strategy to bring people along the journey."

The Manly Warringah Sea Eagles admit they didn't consult players about the jersey, apologising also for blindsiding them.

The club's chairman has said the seven players have already signalled they'll take part in any similar events next season - if they're consulted.

Amid the fallout, the NRL says a competition-wide pride round is on the table for next year.

But how is a jersey going to help anyone? Pride games are actually the most - and arguably only - effective prejudice reduction initiative that researchers have found for sport, Dr Denison says.

Young LGBT players and fans can see role models wearing pride colours.

And research has found, external teams that host pride games use about 50% less homophobic language, and less sexist and racist language.

Fans brought signs celebrating inclusion to Thursday night's game

Supporters are already showing they want better inclusion, argues Sea Eagle fan Hannah McGrory.

"The jersey sold out, so that speaks for itself," she told the BBC.

But the damage from this saga has already been done, some say.

According to one media report, a young gay Sea Eagles player who is yet to come out has felt discouraged from doing so because of the stance taken by his senior club-mates.

"He has been devastated by this turn of events," a friend of the player told local network Nine, external.

"[He] just wanted to play first grade for Manly… he thought they would accept him for who he is if he ever decided to make his sexual preferences public - clearly that is not the case."

You may also be interested in:

"It's my freedom day and I’ve never been so happy" – Josh Cavallo speaks to the BBC

Related topics

- Published5 March 2020

- Attribution

- Published28 July 2022

- Attribution

- Published15 April 2019

- Attribution

- Published21 June 2022

- Published27 October 2021

- Published26 July 2022