Sydney church stabbing: Religious community tensions run high

- Published

A 16-year-old boy has been arrested following Monday's attack

The day after the stabbing attack on a bishop, a forensics expert was sweeping a fingerprint brush over a nativity scene by the entrance of the Sydney church.

A small car parked outside Christ The Good Shepherd Church had its window screen smashed in - a reminder of the horrific event that happened in the western Sydney suburb on Monday night and the mob violence that followed.

Around 19:00 that night, a 16-year-old boy emerged from the congregation of the Orthodox Assyrian Christian church to launch a frenzied attack on the bishop leading the sermon.

Allegedly yelling in Arabic "in the name of the Prophet", he stabbed Bishop Mar Mari Emmanuel, and attacked another priest and churchgoers who tried to intervene.

It was all caught on a live stream - beamed out over the internet to the local congregation and beyond, the news spreading quickly in Assyrian, Maronite, Catholic and Coptic Christian communities.

Hundreds of supporters then descended on the church - clashing with police who had arrived on the scene by then and detained the teenager. The mob, demanding the teenager be handed over, injured officers who were attending the casualties.

Monday night's attack and the frenzy that followed has further shaken Sydney - a city already on edge.

The Australian city was still grieving a mass public stabbing that had occurred two days earlier. In a shopping centre near Bondi Beach, a man stabbed to death six people, five of them women, and injured a dozen more.

As the nation reels from the two attacks, authorities were quick to point out they were not related.

The Westfield Bondi Junction attack appears to have been an act of violence targeting women by a man with a history of mental health problems, while the church attack was religiously motivated, according to authorities. It was deemed a "terror act", New South Wales state police said.

They also happened in two very different parts of Sydney.

The Christ the Good Shepherd Church is located in Sydney's western suburbs: home to most of the city's newly arrived migrant communities, a thriving melting pot of cultures, ethnic communities and faiths, where more than half the residents were born outside of Australia.

In Fowler, the local council district, residents' ancestries reflect that multiculturalism, ranging from Vietnam, China and parts of the Middle East. It is also one of the most religious areas of Sydney, where 25% of the population are Catholics, 19% Buddhist, and 7.5% Muslim, according to the most recent Australian census.

The church is in Western Sydney, an area with a wide range of different faiths and ethnicities

The particular suburb of Wakeley represented the heart of the city's Assyrian Christian community. Just over 40,000 Assyrians live in Australia in total, but more of them live in Wakeley than in any other suburb in the country.

Mostly Christian, Assyrians are native to what was historically Mesopotamia, modern-day Iraq and parts of Iran, Turkey and Syria.

Persecuted for their faith, many fled their homelands over the years, escaping genocide and war to arrive in safe countries like Australia.

So the attack on the church in the heart of the Assyrian community on Monday sparked deep-seated concerns and panic.

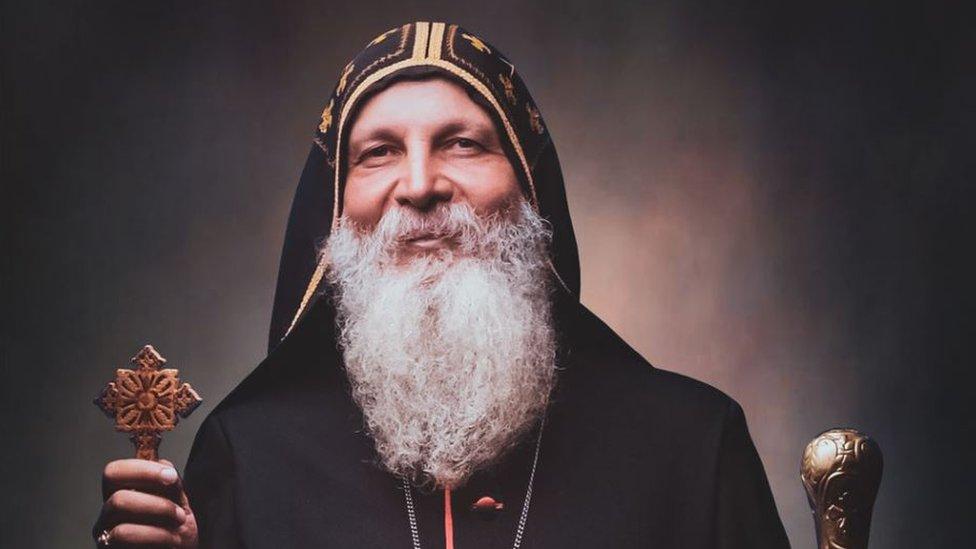

The Orthodox church leader attacked was widely known in the community. Bishop Mar Mari Emmanuel had a huge following online, but he was also divisive and controversial for his ultra-conservative views. During the pandemic, he opposed lockdowns and vaccines; he espoused inflammatory views against same-sex marriage and the Islamic faith.

One of his followers described him to the BBC as a straightforward guy. "He tells the truth, based on his belief in his faith and his knowledge," Basim Shamaon said.

"But we are in Australia - we have freedom of speech. We are in a country where we have to feel safe expressing our views.

Basim Shamaon, who is originally from Iraq, says the attack was traumatising for many refugees and migrants living in western Sydney

"What people saw [on Monday] brought them so many triggers and trauma especially for refugees, migrants and new arrivals," says Mr Shamaon, who is originally from Baghdad. "We don't expect such a thing to happen here."

At the church with her husband and daughter, Merna Taleski told the BBC she'd come to pay her respects to the bishop.

The moment she heard about Monday night's violence, she messaged everyone on her phone. Her mother had fatefully decided at the last minute not to go to the service because she'd been tired, she told the BBC.

"My daughter is nine months old. So at the weekend, I'm thinking I'm not going to the shops any more," says Merna. "And then now it's like, what, do I also stop coming to church?"

Merna Taleski came to the church with her family to pay their respects to the injured bishop

On Thursday, Bishop Emmanuel spoke out publicly, saying he forgives "whoever has done this act".

In an audio message, he said he was recovering quickly and called for the community to remain calm.

But in Wakeley and across Western Sydney, the atmosphere remains fragile and tense.

Despite the multitude of different ethnic communities, the majority of the time they live harmoniously side by side - a fact praised by local leaders. But the act of violence on Monday shattered that peace.

Muslim community leader Gamel Kheir, from the Lebanese Muslim Association, spoke to the BBC about such fears.

He had been with the father of the teenage boy in the hours after the attack. The man was shocked and distraught by his son's violence, telling Mr Kheir he had no idea his son had become so radicalised and that there had been no signs at all. Friends of the attacker at school have since said similarly to local media.

"There was nothing he could see that [his son] had gone that far down," Mr Kheir told the Sydney Morning Herald newspaper.

The man had sought shelter at a local mosque that night for he feared he'd be attacked at the family home, Mr Kheir said.

A wave of threats at Muslim places of worship have been reported since then.

Officials at Sydney's largest mosque, Lakemba Mosque, a half hour drive away from the Assyrian church in Wakeley, reported it had been threatened with firebombing.

Meanwhile community group, the Islamophobia Register of Australia, said it had recorded 46 reports of incidents since Saturday - a "significant spike". That hate has also been driven by misinformation around the Bondi Junction attack where Islamophobes early on labelled the attack as Islamic violence before authorities disclosed details.

"Nerves are so frayed, when the Bondi attack occurred, we were living in fear that a Muslim was the perpetrator," Mr Kheir told the BBC.

There are fears now that police identification of Monday's events as a terror act - when the teenager also showed mental health issues - could inflame hate against his community.

"It's not a healthy society. These events divide us - we need to stay united."

Local parliamentarians and leaders in the area are also making similar calls.

"I am acutely aware of the potential for heightened tensions within our diverse and multi-faith community," said Dai Le, the federal MP for the area, who is herself of Vietnamese heritage.

There was a big police presence outside the church in the aftermath of Monday's attack

She said it was crucial for people to trust police with the investigation and for calm and measured responses.

"I urge everyone in our community to remain peaceful…. It is crucial… that we do not allow fear or anger to divide us."

On Monday, state premier Chris Minns also called an emergency meeting of religious leaders from Muslim and Christian faiths and others to show unity.

All leaders "endorsed and supported a unanimous condemnation of violence in any form, called for the community to follow first responder and police instructions, and called for calm in the community," Mr Minns said.

Listen: Stabbed Sydney bishop forgives his alleged attacker in audio message

- Published18 April 2024

- Published16 April 2024

- Published16 April 2024