Turkey headscarf ban 'humiliating' - student

- Published

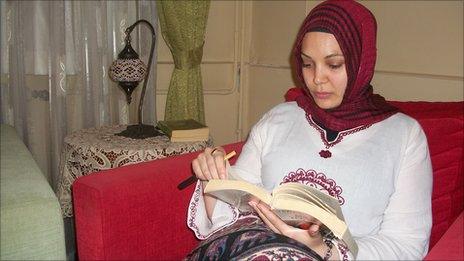

Hilal Kaplan feels the ban discriminates against women like herself and holds Turkey back

Turkey's ban on the wearing of Islamic headscarves in universities and state institutions could rise up the political agenda again if the ruling AK Party wins a key referendum on constitutional reforms on Sunday.

The secular establishment locked horns with the Islamist-rooted AKP on this issue in 2008 and won a court battle, keeping the ban in place.

Hilal Kaplan, 28, is among many Turkish women demanding the right to wear a headscarf in public institutions. Their campaign is seen by secularists as a threat to the state's guiding principles, laid down by its founding father, Mustafa Kemal Ataturk.

Some who are suspicious of the AKP see the headscarf as a symbol of political Islam.

Family tensions

Hilal decided to wear the headscarf for the first time when she was 18, just before beginning an undergraduate degree. She felt that it was part of her identity as a Turkish Muslim, she says.

"My father objected," Ms Kaplan told the BBC World Service.

Her family was worried that she might lose her place at the university if she insisted on wearing a headscarf in her classes.

Some women protested against the headscarf ban in 2008 but the pressure did not get it lifted

Her father thought she was not mentally strong enough to pick a fight with the authorities.

"I had to persuade him to let me wear the headscarf," she laughs.

Now married, Hilal Kaplan is a sociologist working towards a PhD.

Several elderly members of her family wear headscarves but many of the younger generation have chosen not to take it up.

"I thought I would feel weird," she says, speaking of the first time she went out wearing a headscarf. But the transition was not difficult. "I felt quite comfortable," she says, adding that even she was surprised by how easy it was.

'Painful disguise'

She was not, however, prepared for what was coming. Within a year and a half there was an official ban on headscarves at universities.

"It was tough," she says, "my grades fell down a bit, because I was not able to attend lessons".

But then a number of teachers sympathetic to the devout women's headscarf cause agreed to hold informal classes outside the university campus.

"Some of our teachers also agreed to hold examinations there," she adds.

This continued for four months. Then the following year the girls who wore headscarves were able to reach a deal with the university.

"They allowed us to enter the school by wearing hats over our headscarves, in order to disguise them," says Ms Kaplan.

"It was a painful period for me," she says.

"There were security guards at every entrance of the school. Their main work was to check that no headscarf-wearing woman entered the school," she adds.

According to Ms Kaplan, her experience was not only "humiliating and quite absurd", it was also a form of discrimination against women.

She gives the example of her own husband who, she says, is equally religious but is able to attend university without the fear of being penalised.

"I am so fed up with all these stupid procedures that the headscarf ban requires," she says, adding that she often thinks about leaving Turkey to complete her PhD.

Horse carriage v taxi

By preventing headscarf-wearing women from applying for government jobs or higher education, Turkey is failing to take advantage of a large part of its population, says Ms Kaplan.

"Imagine what this does to your productivity, to your modernisation process," she says. And she believes this also perpetuates a class divide in Turkish society.

"If a headscarf-wearing woman wants to work in a factory as a cleaning lady, that's not a problem.

"But if she wants to work as someone who directs that factory, as someone who has a high career, that's a problem," she says.

But not everyone agrees with her, she says.

"I was calling a taxi cab, and a woman yelled at me.

"She said: 'You should only use horse carriages not taxi cabs, who are you to deserve a taxi?"

And this mindset, says Ms Kaplan, is at the centre of the debate over Turkey's Islamic identity.

- Published9 September 2010

- Published12 September 2010

- Published9 September 2010

- Published7 July 2010