Delays bedevil EU help for Roma

- Published

This family was among many cleared from illegal camps in France and sent back to Romania

France's highly controversial deportations of Roma (Gypsies) have put the EU under pressure to tackle a problem that has been festering for years.

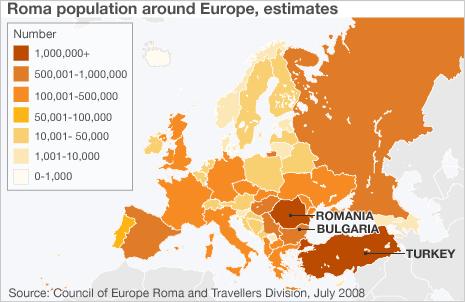

The migration of destitute Roma - often whole families - to Western Europe from Romania and Bulgaria has created one of the biggest challenges for the EU since the two countries joined the bloc in 2007.

The European Commission has castigated France over the mass deportations, while France says it is acting to curb crime and accuses Romania of failing to integrate Roma, many of whom are marginalised and desperately poor.

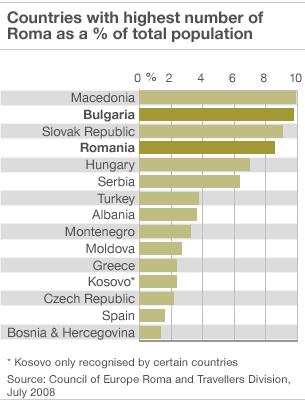

Europe has 10-12 million Roma, more than a million of whom live in Romania.

The migration is largely down to poverty, rather than any nomadic traditions, experts say, as most Roma communities in the former communist bloc have been settled for many years.

Hungary is home to many Roma, but its welfare safety net is much bigger than Romania's, so there is less desperation to flee poverty.

EU funds 'available'

The EU has plenty of funds to help Europe's poorer regions, so why is it taking so long to improve the plight of the Roma?

The Commission says 12 member states have Roma support programmes in place, using EU funds totalling 17.5bn euros (£15bn; $23bn).

Most of that - 13.3bn euros - comes out of the European Social Fund.

The 12 countries include Bulgaria, Romania and their former communist neighbours Hungary, Slovakia and the Czech Republic, which all have large Roma minorities.

The European Regional Development Funds can also be used to get Roma into decent housing.

France's tensions with Romania are similar to those which erupted between Italy and Romania in 2007-2008, when Italy demolished illegal Roma camps and sent large groups of Roma home.

French President Nicolas Sarkozy told an EU summit on Thursday that he is "eagerly awaiting the Commission's proposals" for dealing with the problem of illegal camps, which threaten to become shanty towns. "Europe cannot turn a blind eye to it," he said.

The EU Commissioner for Social Affairs, Laszlo Andor, admitted in April that "too many Roma are trapped in a vicious cycle of poverty, inadequate education, unemployment, bad housing and poor health".

He said a lot of planning had been done, but "not much has changed on the ground".

Tara Bedard of the European Roma Rights Centre (ERRC) in Budapest condemned France for "explicitly targeting the Roma community", but said that at least Mr Sarkozy's campaign had finally put Roma issues "at the centre of Europe's agenda".

The ERRC has been urging the EU for years to adopt a pan-European strategy for the Roma, she told the BBC.

"We need complex programmes. In the past two years it has become clear that if you have a very good housing programme, but don't have jobs, then you quickly lose the housing - people can't afford the upkeep," she said.

Combating segregation

Efforts have been made to end the segregation that blights many Roma communities in Central and Eastern Europe.

But segregation is "still very widespread across Romania" and the efforts have "not had a big impact", Ms Bedard complained.

Measures to integrate Roma children in mainstream schools and spread healthcare among Roma families have had only limited success.

David Mark of the Civic Alliance of Roma, a community welfare group in Romania, praises the EU for making more funds available to help Roma.

The projects have grown since Romania's accession in 2007, he says, but access to the funds is a problem, he told the BBC.

"Romania has had many project management problems - the regulations are too bureaucratic."

He says community groups have to spend money up front and get reimbursed later, but sometimes a delay of three months means a project has no money for equipment.

Romania's introduction of specialist mediators to help Roma families get education and healthcare achieved "very good results," Mr Mark said, but now "they have budget problems and there is a lack of political will".

Sometimes a national project fails at local level, he says, because the authorities on the ground have other priorities.

"Programmes should be implemented at local level, but some mayors don't care - a lot of trained mediators were kicked out."

But he pointed to some promising initiatives, such as the plan to desegregate 100 schools and spread IT skills among the Roma.

The high birth rate among Roma has raised fears of ghettoisation, as Roma-majority communities grow and remain marginalised, the BBC's Budapest correspondent Nick Thorpe says.

It ought to be an incentive for investment in Roma education, according to Bernard Rorke of the Open Society Institute, arguing that the Roma could make a big difference to struggling economies in future, in a region of falling birth rates.

The OSI helps a range of non-governmental organisations working with Roma communities, with projects such as cancer screening, anti-racism awareness campaigns and investment in schools.

But for national impact, Mr Rorke told the BBC, these projects "have to be scaled up one hundred-fold".

"The European Commission should invest far more in building the capacity of Roma civil society. Roma NGOs have great capacities, direct connections with the communities, they can define their own needs," he said.

- Published16 September 2010

- Published14 September 2010

- Published19 October 2010

- Published6 September 2010