Shooting shows risks of European engagement with Libya

- Published

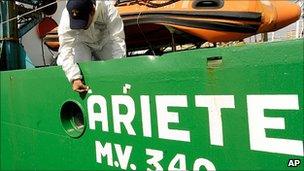

Both Italy and Libya have launched investigations into the fishing boat shooting

There have been plenty of fishing disputes between Italy and Libya over the past few years.

But until a week ago, none had resulted in a dramatic chase across the Mediterranean and an Italian trawler being sprayed with bullets.

The incident, which dominated Italian news in the days that followed, has led to a round of questions about Italy's increasingly close relationship with Libya.

It is also the most recent example of the risks European countries face as they try to consolidate ties with Libya, viewed just over a decade ago as a rogue state.

The details of the clash on 13 September remain murky, but the Italian boat's captain has described the crew diving for cover as bullets rained down. "It could have been a massacre, but luckily we got away," he said.

It has not helped that the patrol boat was one of six Italy gave Libya to help stem the flow of migrants attempting to cross to Europe, nor that it had several Italian officials on board.

Libya has suspended the patrol boat's commander and launched an investigation.

The Italian government has said its officials were strictly limited to the role of observers, but it has been put on the defensive.

"This whole subject of Italian-Libyan relations has become particularly hot," says Ettore Greco, director of the Italian Institute for International Affairs.

'Special relationship'

One reason, he says, is that the shooting incident followed a controversial visit by Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi to Rome at the end of August.

During the trip, what Mr Greco calls the "special relationship" between Colonel Gaddafi and Italian Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi - both leaders who pride themselves on their panache - was on full display.

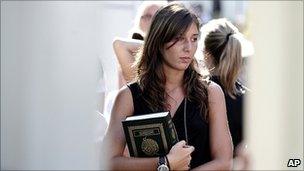

Muammar Gaddafi's lectures to hundreds of Italian women have stirred controversy

And Col Gaddafi repeated an event first staged in 2009 - lecturing hundreds of paid "hostesses", recruited by a modelling agency, on the virtues of Islam. The women were handed copies of the Koran, and a number were reported to have converted on the spot, causing an outcry from feminists and senior Catholics.

The Libyan leader also raised eyebrows by saying Europe should pay Libya billions of euros every year to stop African immigration and avoid Europe turning "black".

The joint effort to block migrants is one of two key areas of co-operation that have been a source of unease for many in Italy and elsewhere in Europe.

While the numbers of people completing the journey have dropped dramatically, activists say migrants risk mistreatment when returned to Libya, and are given no chance to seek asylum.

Their concerns were highlighted when Italian Interior Minister Roberto Maroni said of the shooting incident that the Libyans had perhaps "mistaken the fishing boat for a boat with illegal migrants".

"The Libyans and Italians appear to agree that it was a mistake to shoot at Italian fishermen, but imply that it's OK to shoot at migrants," said Bill Frelick, refugee programme director at Human Rights Watch.

The second area in which the two countries co-operate intensely is the economy. The Italian centre-left says this co-operation has helped legitimise the Libyan regime.

Business deals took off after Italy signed a treaty of friendship with Libya two years ago, agreeing to make investments worth $5bn (£4.2bn) in compensation for wrongs committed during its colonial occupation.

Libya is a major exporter of oil and gas to Italy. It has stakes in Fiat, Italy's largest employer, Juventus, historically its most successful football team, and Unicredit, its biggest bank.

On Friday it emerged that Libya had raised its total holding in Unicredit to 7.6%.

When Antonio Di Pietro, an opposition leader, called for an economic embargo on Libya last week in retaliation over the shooting incident, the parliamentary leader of the governing coalition responded that "a break with Gaddafi would lead to disastrous consequences for our country".

'Volatile'

One reason for nervousness in Italy and other European partners is that since UN sanctions against Libya were suspended in 1999, Col Gaddafi's courting of the West has blown hot and cold, analysts say.

"This is his nature," says Mr Greco, "he's absolutely volatile. We know that Gaddafi is unpredictable in every way."

This has left European states exposed to political risk as they have rushed to build business ties.

In one example, the UK was angered and embarrassed when the suspect in the 1988 PanAm bombing over Lockerbie, Abdelbaset Ali al-Megrahi, was given a rapturous welcome home after being released on compassionate grounds last year.

UK officials denied suggestions that the decision to free him was linked to trade deals.

Switzerland had a row with Libya after arresting Hannibal Gaddafi

But the most notable recent case was a row between Switzerland and Libya, which came after Swiss officials briefly arrested one of Col Gaddafi's sons, Hannibal.

Libya detained two Swiss businessmen, stopped oil exports to Switzerland, withdrew money from Swiss banks, imposed a trade embargo, and even issued a visa ban on Switzerland and 24 other European countries that are part of the borderless Schengen zone.

The episode showed the potential consequences of rubbing Libya's leader up the wrong way.

"The first issue is, is it a rational and stable regime to do business with?" says one former Western diplomat, who did not want to be named because of the sensitivity of the subject. "The answer is it's stable, but it's not always rational in the way others are."

"Other countries have issues that come across from left field, but it's rather more frequent in the case of Libya and that's because it's a one-man show."

Such considerations, combined with the appeal of Libya's hydrocarbons wealth, explain why human rights and political reform have never really made it onto the political agenda in Europe, observers say.

"Libya is beginning negotiations with Europe, so formally there is a clause on human rights with a few political conditions, but it is so weak that I think it's lost its relevance," says Mr Greco.

- Published14 September 2010

- Published20 May 2012