Jerome Kerviel: Rogue trader or folk hero?

- Published

Many praised Kerviel for exposing the flaws in the banking system

Will the tough sentence imposed on rogue trader Jerome Kerviel revive his somewhat jaded image as folk hero for our times?

Back in early 2008 - when his spectacular misdemeanours at Societe Generale first came to light - the 31-year-old from Brittany was lionised by the French.

Internet sites were created in his honour - one was called Kerviel for the Nobel Economics Prize - and thousands of people signed petitions in his defence. At one point his name was the most searched-for in the entire world wide web.

There were T-shirts with slogans like "4,900,000,000 euros - Respect!" and "Kerviel's girlfriend". Someone even wrote a cartoon book chronicling the trader's rise and fall.

This was the year when financial meltdown was permanently in the news. For many in France, Kerviel was the victim of a hideous Anglo-Saxon system finally forced to confront its inherent absurdities.

Some laughed at the humiliation of the hated banks. Others, taking more of the Marxist line, saw Kerviel as the by-product of a speculative machine whose sole purpose was to generate incomprehensibly large paper profits.

All agreed that if he was not entirely innocent, his guilt was certainly relative - and in any case he had done the world a service by exposing the insanity on the trading floor.

Hence, for several months, Kerviel's elevation to a latter day Robin Hood.

But then for some reason, it stopped. The campaigning websites were abandoned, to be replaced by jokes.

The internet spawned a thousand "facts and sayings about Jerome Kerviel".

For example: "When man was bad, God sent the flood. When man was greedy, God sent Kerviel." Or, only slightly better: "For once we get a world champion - and still we complain!"

'Arrogant' reserve

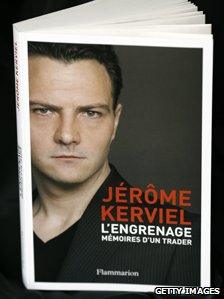

Kerviel's memoirs may have harmed more than helped him

Time passed, and people forgot the seriousness of the issues. Also Kerviel's own image began to suffer.

Just before his trial in June, the former trader released a book - L'Engrenage, or Caught in the System - in which he set out his version of events.

If they were intended to justify his behaviour before the court of public opinion, the book and accompanying interviews smacked rather too strongly of a PR campaign and may well have had an adverse effect.

During the trial too, his demeanour may have put off some erstwhile admirers. By nature taciturn, he often appeared aloof, and his reserve could come across as arrogance.

The Kerviel fan-club had not entirely disappeared, but it had certainly gone to ground.

So is it time for a comeback?

Rightly or wrongly, the verdict against Kerviel - guilty on all charges, three years in jail and 4.9bn euros ($7bn; £4bn) in damages - will be seen by many in France as unduly harsh.

The mainstream view here is that this was a flawed man who was caught in an even more flawed system. He should take his share of responsibility, but that and no more.

Instead, the court's decision will be widely seen as reflecting almost word for word the arguments put forward by the bank.

Many will be reminded of their feeling at the start of the whole affair - that a lone individual is carrying the can.

It may be time to get out those T-shirts.

- Published5 October 2010

- Published5 October 2010

- Published10 June 2010

- Published8 June 2010