France's 'children of the revolution'

- Published

The education system is pumping out a generation whose expectations exceed their prospects

Every morning for the last 10 days, the headmaster at the Lycée Sophie-Germain in the desirable Marais district of Paris has arrived to find a pyramid of rubbish containers piled up against the entrance to the building.

Student leaders take it in turns to climb to the top of the pyramid and harangue their friends with talk of strikes and blockades. Those wishing to attend school are turned away.

The story of the "lycée under siege", and its "suffering headmaster" Michel Vaudry, was told in Le Monde newspaper.

"The worst day was the first, Tuesday, when about 50 troublemakers came, some with death-masks on, some in hoods or with their faces hidden. They attacked us with an almost military precision," Mr Vaudry said.

"They forced us against the entrance with the container-bins, which we were trying to remove, then they started flinging bins and barriers right in our faces … We had to take refuge inside the school."

On another occasion, Mr Vaudry said he was confronted by a young man who was not from the lycée but was clearly organising the protests.

The man took his ground in front of the headmaster and said: "I can't work out what it is that is stopping me planting my fist in your face!"

What is it that makes French students revolt so?

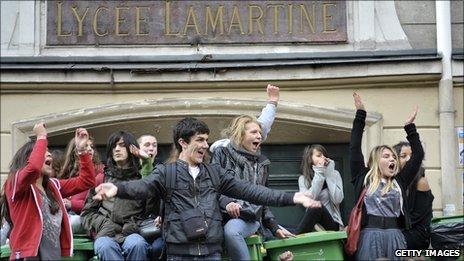

Across the country similar scenes are being acted out daily now, as tens of thousands of lycéens join in the anti-government protests.

A kind of delirium has set in, propelling teenagers onto the streets in a re-enactment of an imagined revolution.

That French lycéens have reason to be concerned about their future is perfectly true.

The school and university system is pumping out generations of youngsters whose expectations vastly exceed their prospects.

Most survive on placements, extra studies and part-time work before finally landing a proper job in their late 20s.

Their argument for opposing Nicolas Sarkozy's pension reform - that the longer old people stay in work, the longer youngsters will have to wait to move into their shoes - may be debatable economics.

But you can see why the future looks less than rosy.

Like in 1968, student protests are still largely a middle-class phenomenon.

And if French students believe they have good cause to protest, the method follows quite naturally.

Carefully handed down from generation to generation, the modus manifestandi has become part of national lore.

Quite consciously, the makers of this student rebellion are acting out the parts created by their forefathers and -mothers in that greatest of all student rebellions: May 1968.

The rituals are identical: the 'general assemblies' in which budding leaders bellow into bull-horns, the arm-link procession, the look of beatific joy.

The slogans are straight from 1968. The students chant: "Sarkozy, t'es foutu, la jeunesse est dans la rue" (Sarkozy you're screwed, the youth is in the street) - which apart from the name is a formulation unchanged from De Gaulle's time.

Bizarrely, even the clothes look the same. Today if you want to look like a student radical, you wear floppy jeans, scarves, hats and badges that could be your parents' castaways.

Some things have changed of course. Today's lycéens have the extraordinary organisational tool which is SMS texting and the internet.

Ahead of each day of action, millions of text messages circulate like wildfire, and the more radical lycées have their own blockade Facebook pages.

Not surprisingly there are suspicions of manipulation.

It would not be hard for far-left groups to infiltrate the movement and incite the protests, though this is vehemently denied by students.

Also today, lycée students have a much greater sense of their own power. Back in 1968 la jeunesse had genuine reasons to feel excluded.

In today's youth-centred zeitgeist, teenagers are constantly being told how important they are.

Middle class phenomena

Ségolène Royal, the defeated socialist contender in the 2007 presidential election, said last week: "At 15 or 16, I believe that young people are responsible and understand why they are taking to the street. What is more I ask them to come down to the street, in a peaceful way."

She denied she was encouraging school children to demonstrate, but how else would you interpret what she said?

One other thing remains unchanged from 1968. The student protests are still an overwhelmingly middle-class phenomena.

Back then they were demanding social change. Today they are demanding the opposite: the preservation of a social system. But in both cases, those protesting are not the poorest.

Michel Vaudry noticed the same thing at his besieged lycée in the Marais.

"The ones who are doing the blockading, above all they are ones who are best-off - the ones who have nothing to lose because their parents can always pay for private lessons so they can catch up," he told Le Monde.

- Published10 November 2010