UK wins allies in EU budget battle at summit

- Published

Mr Cameron (right) lobbied hard to put the EU budget issue on the agenda

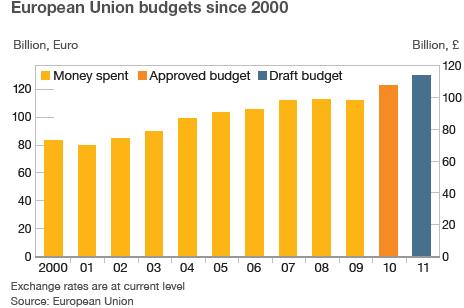

Ten EU countries have rallied behind the UK's call to limit an increase in the 2011 EU budget to 2.9% - well below the rise that Euro MPs called for.

France and Germany are among the group backing UK Prime Minister David Cameron on the budget.

The issue was not formally on the agenda at the Brussels summit, but Mr Cameron insisted that the EU should set an example of budget prudence.

Tough talks lie ahead with the European Parliament, which wants a 5.9% rise.

The European Commission - the EU's executive arm - is on the parliament's side in calling for 5.9%.

If no compromise is reached by a mid-November deadline the budget will remain frozen at the 2010 figure. A freeze was what Mr Cameron was originally calling for, but other EU leaders refused to back the idea.

In a letter to the European Council President, Herman Van Rompuy, the 11 leaders say the budget proposals from the Commission and the parliament "are especially unacceptable at a time when we are having to take difficult decisions at national level to control public expenditure".

They say they cannot accept any more than 2.9% - the increase agreed earlier this year by the Council.

That rise would still cost UK taxpayers an estimated £435m (nearly 500m euros).

Thorny treaty question

The main focus of the summit talks on Thursday was a plan to tighten EU budget surveillance, to prevent any future debt crisis like the one which triggered an emergency bail-out for Greece in May.

EU leaders backed a report by a European Council task force on measures to strengthen economic governance in the EU, external.

But the leaders remained divided over whether an EU treaty change would be needed to make a crisis mechanism legally watertight.

An array of sanctions is envisaged, including fines and even stripping a country of its EU voting rights if it persistently overshoots the agreed limits for budget deficits and public debt.

The EU created an emergency 440bn-euro (£386bn; $612bn) fund called the European Financial Stability Facility (EFSF) to protect any EU member states vulnerable to Greek-style liquidity problems.

But the EFSF only runs until 2013, so France and Germany are arguing for a permanent shield to protect the eurozone.

German Chancellor Angela Merkel says that requires a treaty change because the Lisbon Treaty does not allow any country to be bailed out by other member states.

She also wants more clarity and legal certainty on the emergency funding arrangements, so that in future the banks take some of the burden off taxpayers for any bail-out.

Pressure for referendums

But several other EU leaders signalled that there was little appetite for rewriting the Lisbon Treaty, which was only adopted after eight years of tortuous negotiations.

The BBC's diplomatic correspondent Jonathan Marcus says a revision of Lisbon would create major domestic political problems in many EU states, with referendums or embarrassing parliamentary votes.

The likely outcome is that Mr Van Rompuy will be sent away to explore how some kind of compromise might be stitched together, our correspondent says.

The permanent crisis mechanism is intended to prevent contagion spreading among eurozone economies should there be another major debt crisis in one of the weaker members.

The UK says a mechanism to ensure stability in the eurozone is desirable - and that the planned sanctions would not apply to the UK. But all 27 member states' budgets will come under close scrutiny in a "peer review" process.

There would be progressive sanctions on countries which overshot the maximum debt level allowed under the EU's Stability and Growth Pact (SGP), which is 60% of GDP.

Sanctions would kick in earlier than is the case under the current SGP, enabling the EU to take preventive action for example against a country with an unsustainable housing bubble or with unsustainable debt that undermines its competitiveness.