EU leaders frame eurozone crisis rules

- Published

Mr Cameron (right) lobbied hard to put the EU budget issue on the agenda

Tough rules for the eurozone, aimed at averting another financial crisis, have been agreed at an EU leaders' summit.

The leaders agreed to a permanent fund to help the euro in times of crisis, and to laws giving the EU the power to check national budgets.

EU officials said the eurozone had almost collapsed earlier this year because it lacked such a mechanism.

Germany wants limited changes to the EU treaty to reinforce the changes, but is facing resistance from other countries.

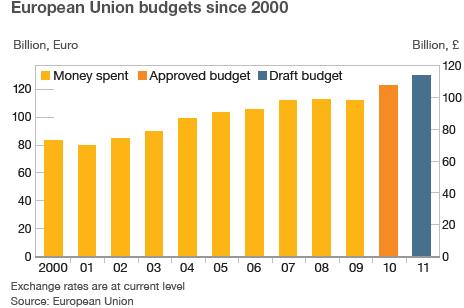

Meanwhile, UK Prime Minister David Cameron won backing for his battle against a 5.9% rise in the EU budget.

Germany and France were among 10 nations supporting Mr Cameron's attempt to limit the budget increase to 2.9% - a rise that would still cost UK taxpayers roughly £435m (500m euros).

The meeting will conclude later on Friday.

Treaty question

The BBC's Jonty Bloom, in Brussels, says the new eurozone rules are designed to force a country to put its house in order long before its economic problems threaten the eurozone.

Herman Van Rompuy, the President of the EU Council, hailed the summit's achievements, saying: "Today we took important decisions to strengthen the eurozone.

"We recommend a robust and credible permanent crisis-resolution mechanism to safeguard the financial stability of the eurozone as a whole."

Under the new rules, EU officials will warn governments about property and speculative bubbles, and will be able to impose stringent fines on countries that borrow and spend too much.

The permanent crisis fund will replace a temporary one, worth 440bn euros, created earlier this year to bail out Greece and support the euro.

But Germany has argued that the Lisbon Treaty will have to be amended to make the emergency fund permanent and legally watertight.

The current treaty contains a clause banning members from bailing each other out.

"Everybody agreed that there must be a permanent crisis mechanism, and everybody agreed that this must be formed by the member states," said German Chancellor Angela Merkel.

"Everybody therefore agreed that this will require a limited treaty change."

It took almost a decade of hard negotiations and two referendums in the Republic of Ireland to ratify the Lisbon Treaty, and many states are reluctant to make a move which could trigger a similar process.

The EU Constitution - the treaty's ill-fated forerunner - was rejected by voters in France and the Netherlands.

Mr Van Rompuy has been tasked with finding out whether the fund can be set up without each of the 27 member states having to ratify the treaty all over again.

The UK says a mechanism to ensure stability in the eurozone is desirable - and that the planned sanctions would not apply to the UK.

But all 27 member states' budgets will come under close scrutiny in a "peer review" process.

There would be progressive sanctions on countries which overshot the maximum debt level allowed under the EU's Stability and Growth Pact (SGP), which is 60% of GDP.

Sanctions would kick in earlier than is the case under the current SGP, enabling the EU to take preventive action, for example against a country with an unsustainable housing bubble, or with mounting debt that undermines its competitiveness.